|

A Trip Into The Past: Part 4 by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

In this section, I want to look at an issue of The West American Scientist, Vol. VI, June, 1889, Whole No. 44, edited by C.R. Orcutt, published by Samuel Carson & Co., San Francisco, California. The magazine is further described as: “A popular monthly review and record for the Pacific Coast. Official Organ of the San Diego Society of Natural History”. It cost 10 cents per issue or $1.00 per year.

The articles here are certainly a cut above those in the publications we considered previously as are most, but not quite all, of the advertisements. As we have come to expect, the editor regarded it as virtually obligatory that he take advantage of the opportunity to advertise his wares and Mr. C.R. Orcutt presents us with 2 full pages, 4 columns each, of shells he has for sale and the print is small, so he is offering literally about 600 species ranging in price from 5 cents to $2.00–a rather remarkable offering even by today’s standards.

The publisher, Mr. Samuel Carson & Co., more modestly advertises his Book Home in a 1/3 page ad.

As we have seen previously, all of these little journals compete aggressively for subscribers by offering premiums and this magazine is no exception. If you subscribe for a year, you could receive 100 bulbs of Freesia refract alba, but if you’re not a Freesia fan, not to worry, you can substitute:

1) A collection of 20 named shells.

2) A collection of 20 varieties of seeds of wild flowers.

3) A collection of 12 varieties of California bulbs.

4) A plant of Anemopis. (Also known as lizard tail and yerba mansa)

5) A bulb of the Black calla.

6) Ten White calla tubers.

7) Subscription to one copy of “Fruits All the Year Round”.

8) Five named cactus plants.

and whatever your final choice, it was postpaid. Amazing what $1.00 would buy in those days, if you were so lucky as to have a spare one.

As you have doubtless noticed, my fascination with advertisements has dominated and I have turned to them first.

The inside cover has 2 ads, one for an insurance company and the other for The Cosmopolitan “That Bright Sparkling Young Magazine” which we are informed provides over 1,300 pages annually for a mere $2.40 per year, but if you order both The Cosmopolitan and The West American Scientist, you’ll pay only $2.75, a saving of 65 cents.

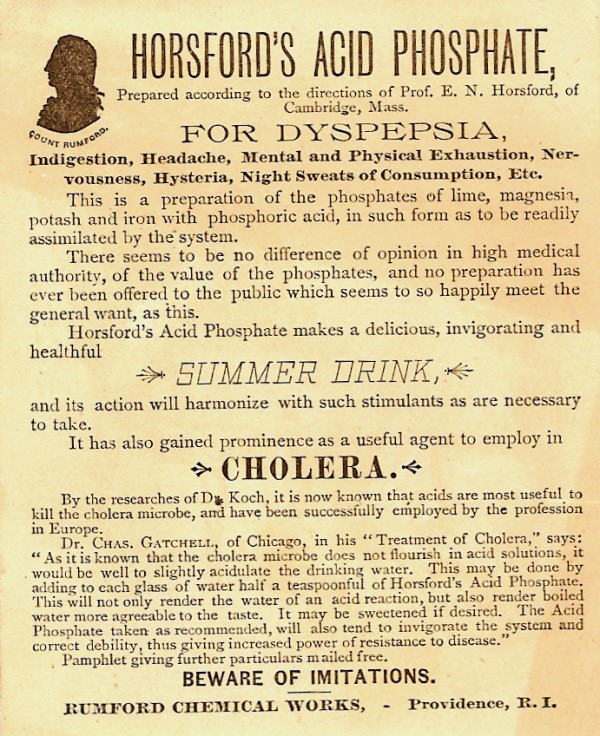

However, there are some real advertising gems on the next 2 pages. The next page is a full page ad for

Horsford’s

ACID PHOSPHATE

which was “especially recommended for Dyspepsia, Nervousness, Exhaustion, Headache, Tired Brain and all Diseases arising from Indigestion and Nervous Exhaustion.”

I love the Tired Brain reference; I’m gong to order a case of Horsford’s or its equivalent which it turns out wouldn’t be difficult. Horsford was a Harvard-educated chemist who worked for the Rumford Chemical Company Works of Providence, Rhode Island. He was beloved by bakers and housewives because he invented baking powder–replacing cream of tartar with calcium acid phosphate. The elixir “a delicious drink with water and sugar only” was the cure for Tired Brain. Most of you are, I suspect, too young to remember what a soda fountain is–and, no it’s not Trevi filled with Coca Cola. At one time, soda fountains were a significant institution in America. You could go sit at a long counter and tell the soda jerk (I’m not being insulting; that’s what they were called) you wanted to order a cherry coke or a Green River or any number of other concoctions that would rot your teeth and the soda jerk would squirt some concentrated syrup into the bottom of a glass and would then fill the glass with carbonated water by jerking down on the handle that dispensed the water—thus his descriptive name. You could also order a cherry phosphate–cherry syrup and (guess what) acid phosphate. So, in the old days, if you had a tired brain, you could just pop down to your local soda fountain and have a cherry phosphate with your friends. (As a matter of fact, many soft drinks still contain phosphoric acid.)

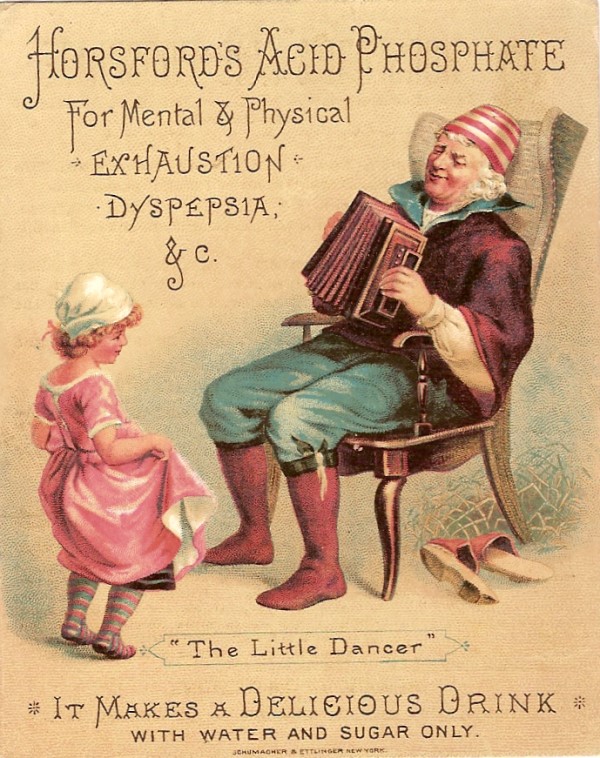

Horsford’s Acid Phosphate was also popular in England and a number of trade cards advertising it were issued. I was able to find an exceptionally well-preserved one on the internet and I bought it, so I’ll share it with you here.

The colors are quite bright and the elderly man looks quite content as the little girl dances to the music of his little accordion, which reminds me of the anonymous definition of a gentleman: “A gentleman is a man who can play the accordion but doesn’t.”

Here we are informed of all of the virtues of the product and told that not only is it a pleasant summer drink, but that it is a “useful agent to employ in CHOLERA” and a testimonial by a doctor regarding such use. At the very bottom, we are, as we should expect, admonished to “BEWARE OF IMITATIONS”. Rumsford Chemical still exists, but has moved to Terre Haute, Indiana and now sells baking powder under the name of Clabber Girl.

The next page has advertisements for 3 models of Acme microscopes, a brand I had never heard of. The Acme #3 was apparently the top of the line “for finest work”.

It was configured with: “3.5 inch and 1.5 inch objective, 2 eyepieces (power 60 to 700), glass slides and cover, in case–$83.00"’

You could get the same instrument with a 1.5 inch oil immersion objective and a substage condenser which would provide magnifications from 50 to 1600 for $150. Of, course, that was a substantial sum in 1889. If you feel that you missed out, I have good news; these were quite nice instruments in a beautiful brass finish and you can still get one. I went on the internet and found a dealer in old instruments and there is a picture of a very handsome Acme #3 for the bargain price of $3,750! If you would like to take a look at it, you will find some pictures here:

http://www.gemmary.com/con/US/US-810.html

The Acme #4 with a 1 inch and a 1.5 inch objective and 2 eyepieces with magnifications from 40 to 600 was only $55.00. Today, you can have that instrument for only $1,270.

http://www.arsmachina.com/squeen1196.htm

The Acme #5 was “an instrument of simple but thorough construction, with good lenses, and at a minimum cost.” It had a 1 inch and 1.5 inch objective and one eyepiece providing a magnification range of 40 to 360 for $28.00.

On the back cover is a full page ad for the insurance company, Firemans Fund of California of San Francisco with branches or agents in Chicago, Boston, Denver, Los Angeles, Salt Lake, San Diego, Sacramento, Portland, Oregon, Helena, Montana, and Honolulu. At this time, Salt Lake was still part of the Montana Territory. On the inner back pages, there are 2 modest-size ads by banks of modest assets compared with the insurance company which in capital and assets was worth $3,350,000, whereas one of the banks had assets of $375,961 and the other capital of $100,000. What interests me is that whenever anything lucrative is taking place, wherever it is taking place, one inevitably finds banks and insurance companies. There are some people who always seem to operate on the principle: Use other people’s money; never risk your own.

There are 4 advertisements (although 2 of them were for the same company) for plants and for 2 of these companies, Charles Russell Orcutt was the agent. The firm was located in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). This is not as surprising at it might seem at first, because Orcutt was a passionate, nay, obsessive, collector of plants and shells. He and his brother never attended school and were taught by their parents. This may in part explain the rather erratic character of Orcutt’s enterprises. He had a great need to be recognized by the scientific community of the day and kept careful track of the plants and shells which were named after him. He started The West American Scientist in 1884 at the age of 20 and it appeared off and on until one year after “The Great War”, viz., 1919. However, more of Mr. Orcutt a bit later.

From Mr. J.P. Abraham in Ceylon, you could purchase orchids, cycads, and lilies; bird skins of over 50 species unique to Ceylon and eggs, shells, bones; bulbs, seeds, and roots of “Coffee, Thea, Cinchona, Peppers, Palms, etc. etc.”

Orcutt was also an agent for B.F. Johnson & Sons of Zenos in the Arizona Territory who sold The Giant Cactus, the “Monarch of the Desert” for $5 to $100 depending on size. These were the famous Saguaro cactus on the Sonoran Desert and they could achieve a height of 50 feet and weigh 10 tons! I wonder what size one got for $100?

His father established a small horticultural nursery near San Diego and Charles and his father collected extensively in the surrounding areas and when he was 18, they went on an expedition into Baja California with a group of botanists. His passion for collecting intensified and he was soon amassing an enormous array of both plant and shell specimens. In 1892, when he was 28, his father died which was a major blow to him. In that same year, however, he married a young woman, Olive E. Eddy, who was a doctor and over the next 6 years, they had 4 children. He was extraordinarily fortunate in his choice of a wife, for he was essentially a loner and, in his middle and late years, his collecting became such an obsession that he was at home less and less and during the last 7 years lived almost completely apart from his family. He collected extensively in California, Arizona, Texas, Mexico, and later Jamaica. In many respects he was a vagabond and was always short of money. Periodically he would try selling parts of his collection and then there were his publishing ventures, but none of this produced enough money to sustain him. He was not reluctant to sponge off of acquaintances and to exploit any opportunity that presented itself along the way. However, his financial mainstay became his wife and although she had a solid medical practice, she also had 4 children to support–5, if you count her husband.

His collection was a large, haphazard affair and so extensive that he had to rent storage spaces and eventually a warehouse. He dreamed of having his own museum, but that was a large and expensive undertaking. Finally in 1918, he offered his entire collection to the San Diego Society of Natural History and then negotiated with them for 10 years. During this period he continued to add to the collection and to sell and trade items from it. The tension between Orcutt and the Society continued to grow until at last he demanded $500 for the whole assemblage and insisted that the money be sent to his wife; the Society eventually sent her $750 for the collection and shipping expenses. He died in Haiti in 1927. [The biographical specifics I have derived, in part, from Anne D. Bullard’s essay “Charles Russell Orcutt: Pioneer Naturalist” published in The Journal of San Diego History, Winter 1994, Volume 40, Number 1& 2.]

Before I get to the content of the articles, however, there are 3 more ads I wish to ramble about; two of them regarding pocket watches. Pocket watches were very popular in the 19th Century and the Keystone Watch Club Co. of Philadelphia offered such a watch for $38 which they asserted was “fully EQUAL for Accuracy, Durability, Appearance and Service to any $75.00 Watch.” For a mere $10 more, you could get their “14-Karat Gold filled CHAIN...guaranteed to wear 20 Years, and [which] is 33 1/3% 14-Karat Solid Gold.” Even though I have a degree in mathematics, I have a bit of trouble with the last bit of this ad and, as a philosopher, I sometimes get rather picky about language usage. If it’s a filled chain, how can it be solid gold, especially when it’s only 14-Karat and only “33 1/3% 14-Karat Solid Gold” at that? Perhaps the description of its being solid gold is simply to assure us that it isn’t liquid.

The second ad is even more interesting, because you can get an “$85 Solid Gold [here we go with the ‘solid gold” again] Watch–FREE. Sold for $100 until lately.” Not only that, you also get a set of household samples. “These samples, as well as the watch, we send Free, and after you have kept them in your home for 2 months and shown them to those who have called, they become your own property.” This irresistible offer was made by Stinson & Co. of Portland, Maine. Today we have Amway and Avon, but they get the money up front and I strongly suspect that Stinson & Co. was not as generous and trusting as the advertisement suggests, but if you think so, I’ll make you a terrific deal on the Brooklyn Bridge.

To me, the most fascinating and remarkable ad is a small one at the bottom of the first column of the inside back cover. It is short enough that I will quote it in its entirety.

A Letter From Dr. Hans von Bülow

The Knabe pianos, which I did not know before, have been chosen for my present concert tour in the United States by my impresario and accepted by me on the recommendation of my friend Bechstein, acquainted with their merits. Had I known these merits as now I do, I would have chosen them myself, as their sound and touch are more sympathetic to my ears and hands than all other of the country.

New York, April 6, 1880

So, what’s the big deal? Well, there’s a lot of music history of the 19th Century in the style of a Grand Soap Opera associated with von Bülow and for this notice to appear in an erratically published West Coast natural history magazine in 1889, nine years after his concert tour is, to me at least, exciting and slightly bizarre.

Hans von Bülow was probably the most brilliant pupil of the great Hungarian composer and pianist, Franz Liszt. However, he began his musical education under Friedrich Wieck, the father of Clara Schumann. Six years after he became a student of Liszt, and he married Lizst’s illegitimate daughter, Cosima, and they had 2 daughters. He established a significant reputation as a virtuoso pianist, a composer, and a conductor. He had also met Richard Wagner and had become a champion of his music. In 1864, in large part due to the influence of Wagner, he was appointed Court Conductor by King Ludwig II of Bavaria, also known as the “Mad Ludwig”. Wagner had sought refuge in Munich after having been exiled from Dresden for his outspoken political views. In Munich he found the ideal patron–Ludwig, who was entranced with Wagner’s music and indulged him in an opulent lifestyle. However, Ludwig was soon to have major political difficulties of his own. His great passion for music was second only to building castles. If you’re not familiar with his fairy tale castle Neuschwanstein in its magnificent setting in the Bavarian Alps, then take a look at it here:

http://www.castles.org/castles/Europe/Central_Europe/Germany/germany7.htm

or simply search on Google.

During part of the period of construction, Ludwig lived in a worker’s hut and supervised the activity. His bedroom had a sphere, with an open bottom, made of cobalt blue glass into which a candle could be inserted to simulate moonlight. Neuschwanstein boasts an ornate chandelier made of Meissen porcelain which 50 years ago, a wealthy American offered $5,000,000 for. His offer was refused. Ludwig had built a more modest castle called Linderhof. In the main courtyard is a pool with a fountain and, in the pool, statues of human figures gilded in gold. There was also a grotto in the hillside which had a pool and a small boat in the form of a sea shell which Ludwig used to paddle around in when he felt depressed. Ludwig was, apparently, a manic-depressive or in modern jargon, “a bipolar personality.” All of which just goes to prove that enormous wealth, influence, and pampering don’t necessarily make one happy; still I would have liked to have learned that lesson for myself. Ludwig’s most ambitious project was Herrnchiemsee–a castle built on an island in the middle of a lake and modeled on the Palace of Versailles; it has a Hall of Mirrors with chandeliers containing 4,000 candles. This castle was never finished. Ludwig’s constructions were works in progress and he was already planning yet another one Falkenstein. This was becoming an outrageously expensive hobby and the ministers of the Bavarian government finally forced Ludwig to abdicate the throne.

Ludwig had manifest paranoid tendencies and at Linderhof in the hall where he dined, the entire table could be lowered through the floor into the kitchens, the repast arranged on the table, and the table raised back up to the dining hall. Although he dined alone, the table had to be set for at least four people. Ludwig didn’t want servants lurking beside or behind him. After his forced abdication, he was declared insane by Professor Gudden (although he had never examined Ludwig) and placed in his care. He was arrested on June 10, 1886 and on June 13 both Ludwig and his Dr. Gudden were found drowned at the edge of Lake Starnberg. Many believe that Ludwig was the victim of political intrigue and that his death was an assassination. So, perhaps he wasn’t so paranoid after all,

Wagner had become a political embarrassment in Munich and left for Switzerland. Cosima von Bülow went with him and they took 2 of the 4 von Bülow daughters along–the 2 that Wagner had sired and 2 years later, Cosima divorced von Bülow. Hans von Bülow apparently prized Wagner’s music more than he did Cosima for he continued to conduct and champion Wagner’s music and showed no sign of holding a grudge.

In Switzerland, the Wagner’s had an estate outside of Basel called Triebschen and it was here that Wagner and Nietzsche renewed their acquaintance. Nietzsche was teaching at the University of Basel; Wagner was dreaming of having his own opera theater and pulled Nietzsche into helping bring this dream into reality–the Opera House at Bayreuth. This project had had the support of Ludwig II, but Wagner needed additional funds and in the end the project was scaled down. Nietzsche, who at this time was an enthusiast, was, by the time Bayreuth opened thoroughly disillusioned with Wagner. Nietzsche was a pianist of some talent and is reported to have had remarkable improvisitory abilities. He also had a passion to compose. He once sent one of his compositions, a work called Manfred Meditation to von Bülow, whose response is a masterpiece of critical invective.

“Your Manfred Meditation is the most fantastically extravagant, the most unedifying, the most anti-musical thing I have come across for a long time in the way of notes put on paper. Several times I had to ask myself whether it is all a joke, whether, perhaps, your object was to produce a parody of the so-called music of the future. Is it by intent that you persistently defy every rule of tonal connection, from the higher syntax down to the merest spelling? Apart from its psychological interest–for your musical fever suggest, for all its aberrations, an uncommon, a distinguished mind—your Meditation, looked at from a musical standpoint, is the precise equivalent of a crime in the moral sphere....But if you, highly esteemed Herr professor, really take this aberration of your into the field of music quite seriously (as to which I am still doubtful), then, at least confine yourself to vocal music and surrender to the words the helm of the boat in which you rove the raging seas of tone. You yourself, not without reason, describe your music as ‘terrible.’ It is indeed more terrible than you think–not detrimental to the common weal, of course, but something worse than that, detrimental to yourself, seeing that you can find no worse way of killing time than raping Euterpe in this fashion.” [from Ernest Newman, The Life of Richard Wagner, 4 volumes, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946, vol. IV, p. 324.]

From this you can see why von Bülow had a reputation for being tactless.

In the mid 1870s, von Bülow did a concert tour of America and this prompted his brief letter of endorsement of the Knabe pianos which he tried out “on the recommendation of his friend Bechstein.” Bechstein was the head of a company that produced exceptionably fine pianos in Berlin and Liszt owned one which you can still see in the Liszt House if you visit Weimar.

Isn’t it grand where a small advertisement in an obscure 19th Century natural history publication can lead you?

So, I can hear you impatiently demanding–what about the articles? Well, remember that Orcutt was not only an eccentric, but something of a self-promoting egomaniac. There is good reason to believe that his ventures into publishing were primarily to provide a forum for the presentation of his own work. The first article “Some Native Forage Plants of Southern California” is by C.R. Orcutt followed by a poem by E.E. ORcutt (presumably his wife), followed by “An Indian Myth” by C.R. Orcutt, the 3 pages of contributions from the San Diego Biological Laboratory by C.H. and R.S. Ergenmann, a “List of Beetles of the Genus Amara Taken Recently in Colorado” by T.D.A. Cockrell which consists of ½ page, a bit further on a page of “Mineralogical Notes by George F. Kuntz. There is also ½ page devoted to visitors’ hours for the Lick Observatory. The briefer articles, the editorial the “Note and New”; several of the book reviews and the proceedings of scientific societies were all either written or compiled by Orcutt.

This little publication is full of interesting tidbits and is a strange mixture of folksy, personal observation and sound scientific observation. Only at the very end of his life did Orcutt get a bit of the recognition he so desperately desired. The Smithsonian put a technician to work cataloging the material which he had sent to them from Jamaica and provided a bit of funding for him to collect material in Haiti. Orcutt was clearly an individual whose restless passion to explore nature brought him joy, hardship, disappointment, excitement and frustration; but I suspect that he was rarely bored.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .