|

|

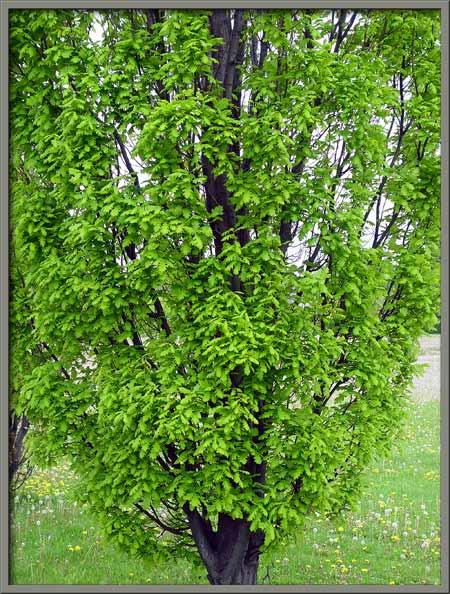

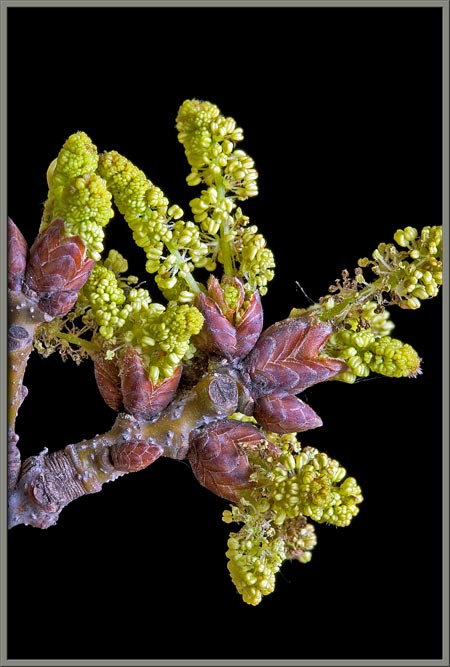

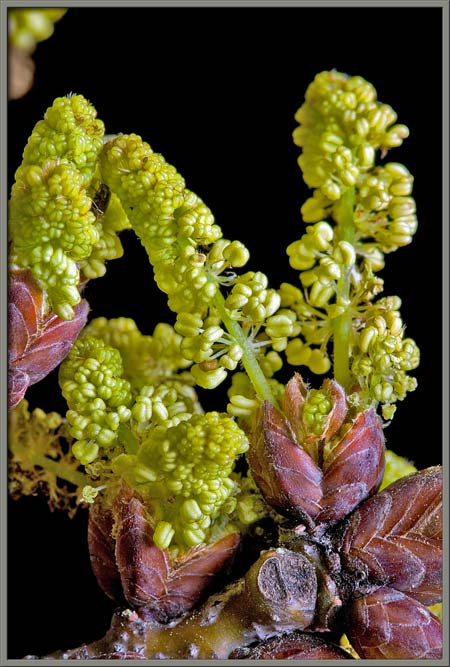

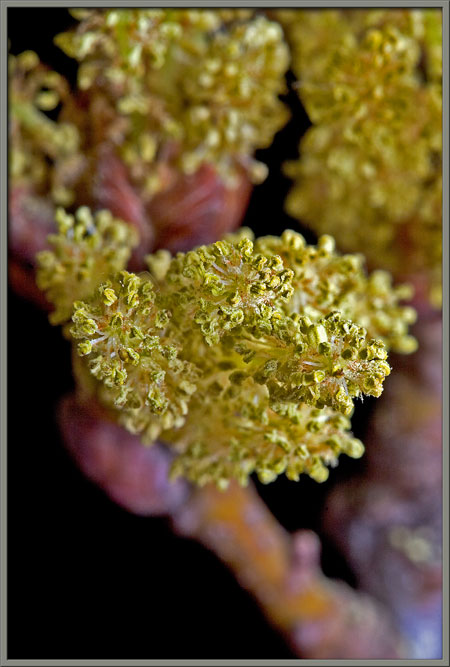

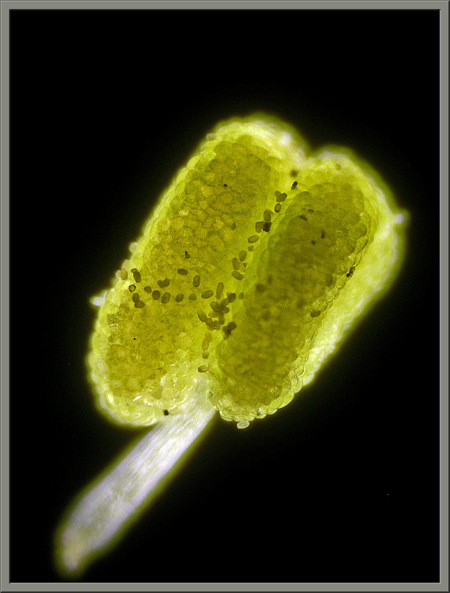

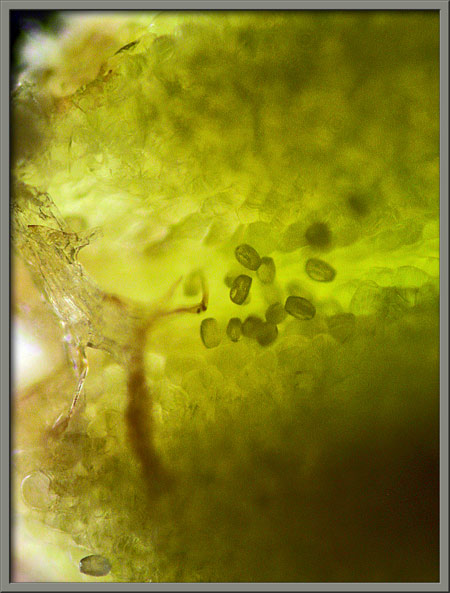

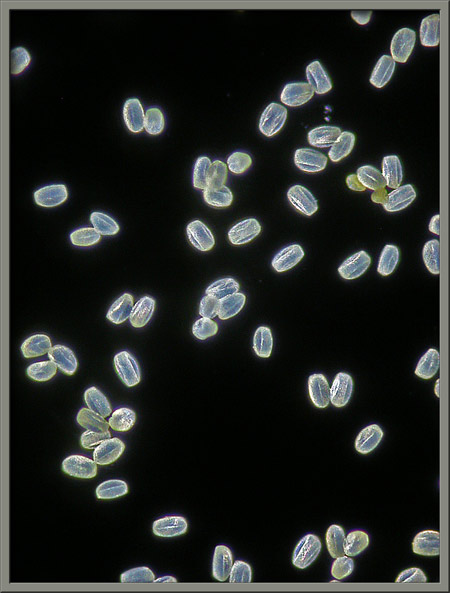

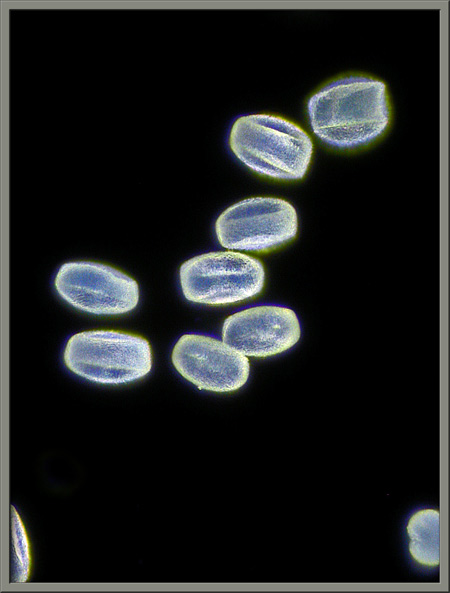

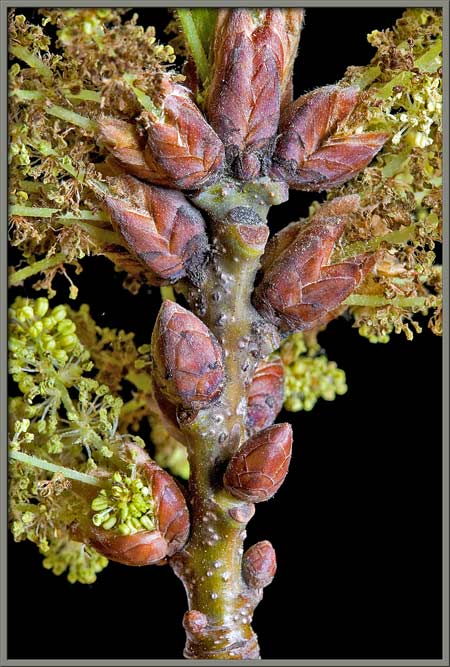

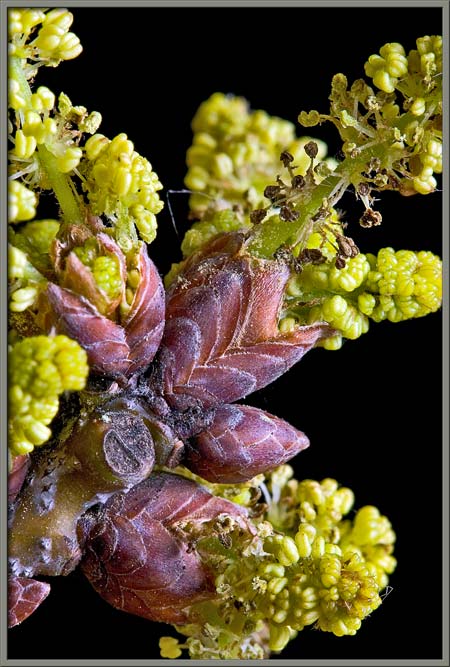

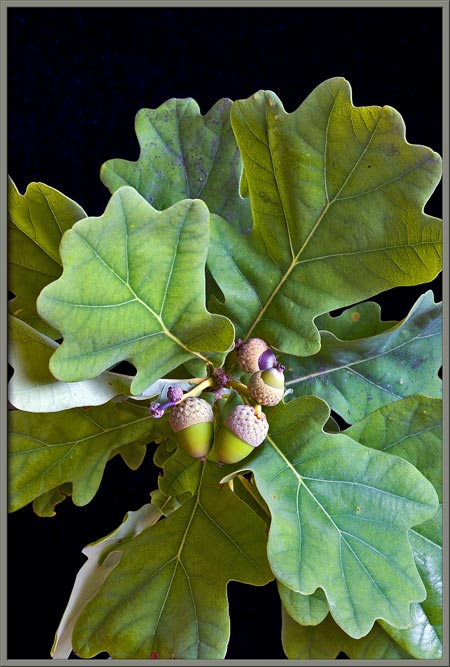

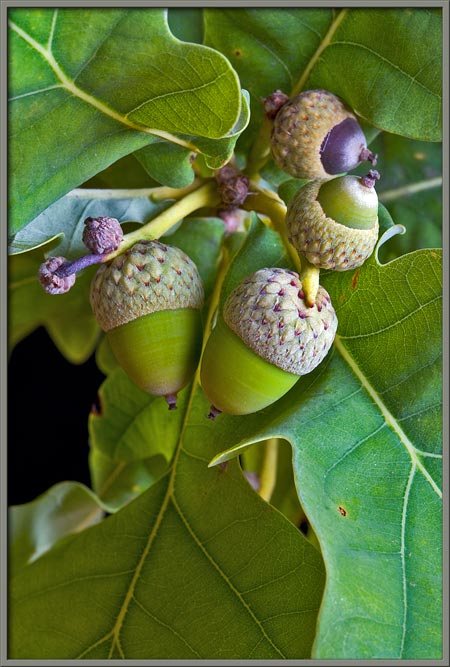

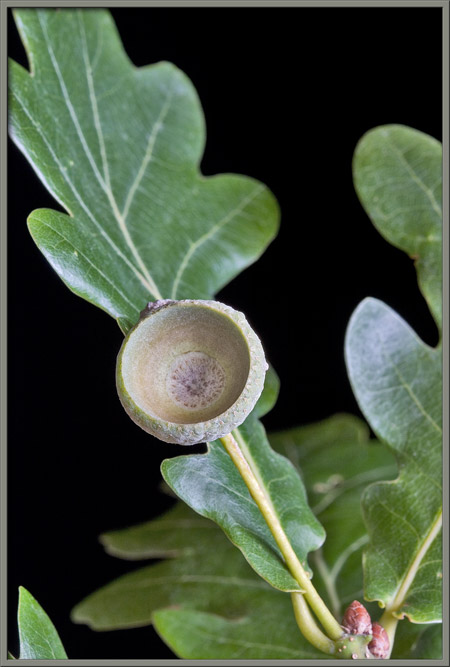

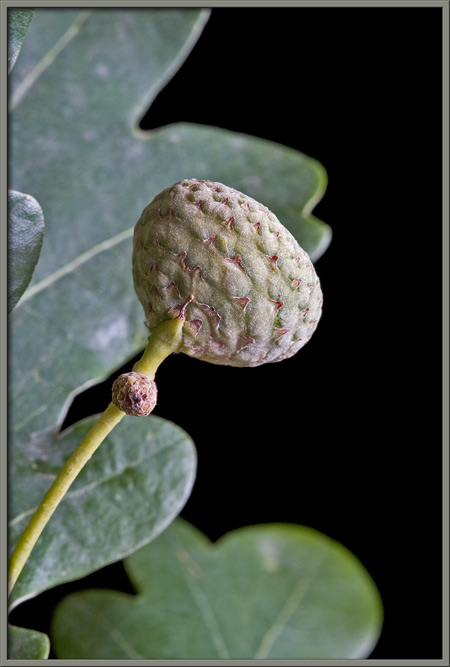

A

Close-up

View of the

English White Oak

|

|

|

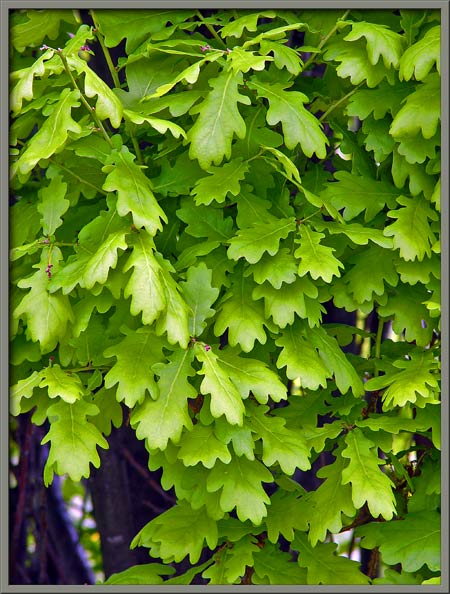

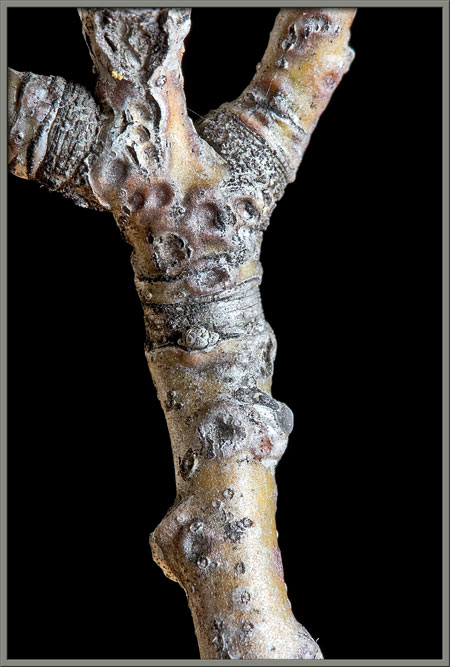

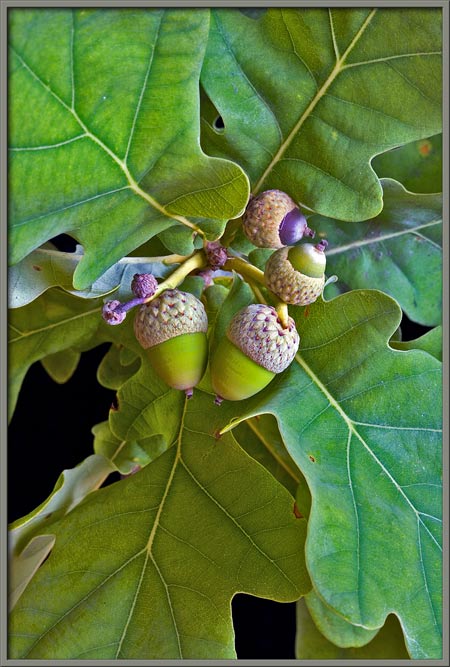

A

Close-up

View of the

English White Oak

|

Published in the April

2009 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .