John William David Hume (1851 – 1912)

Pharmacist and Mounter

Peter Paisley, Sydney, Australia

John Hume was born in 1851 in Seamer, a Yorkshire village near the seaside spa town of Scarborough. His parents, John and Mary, were teachers at the local school. The 1861 census shows young John and his sister Emma at school in Seamer, and another infant sister, Gertrude, at home. The 1871 census lists him as a chemist’s assistant, again at home in Seamer. No record of a pharmacy in Seamer can be found by local historians there. He was probably at home on holiday when that census was taken, since not long thereafter he was in Gloucester for three years (1876 – 1878), and registration there with the Royal Pharmaceutical Association on December 13 1876 implies some years’ prior training. Regrettably, the Association’s archives yield no records of with whom pharmacists trained in that era, nor details of any training in addition to assistantships. Two Gloucester addresses are recorded by Royal Pharmaceutical Association Yearbooks. 75 Northgate St. seems mistaken: a chemist, William Willis, lived (1861 census) at no. 45, with an apprentice; and (1871 census) at no.33 (with no apprentice, but see below), both in Northgate St. Another chemist, Richard Brooks, with no assistant, was at 69 London Rd. (the direct continuation of Northgate St.) No number 75 existed then (or now) in Northgate St. I consider 33 Northgate St. Hume’s likely trainee workplace: Willis’ previous address at no.45 was presumably retained (and misprinted as 75) by the Association, explaining the yearbook discrepancy.

Forming an intersection with Northgate St. is Worcester St. In a modest but elegantly proportioned Georgian house at no. 16 lived Alfred Webb, his wife Jane, daughters Matilda and Annie, and a son, Alfred junior. Alfred senior was a rates and tax collector and housing rental agent: remarkably, the residence exists today with the upper floors little altered, and a housing rental agency in the modernised ground floor shopfront. Annie was 15 years old in 1871, and since Hume gave the Association 16 Worcester St. as one of his addresses, he almost certainly boarded with the Webb family, serving as a chemist’s assistant just round the corner with Willis, and becoming enamoured of Annie. By autumn 1875, they were married.

Some botanical material, perhaps thought of as "typical" Hume preparations.

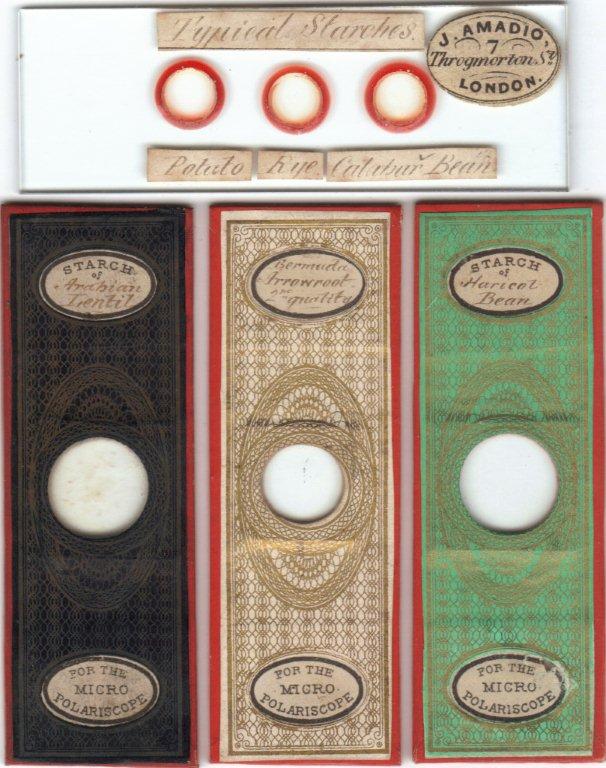

The move from Seamer to Gloucester is somewhat mysterious – the centre of a major Georgian city in the west country was far, geographically and socially, from a bucolic village in east Yorkshire. A generation before, the fame in chemistry of the Bristol medical school – not very far from Gloucester - had increased, due to the work of the Herapaths: their observations under polarised light had sparked considerable revolutions in experimental chemistry and microscopy. An interest in both may have prompted the young Hume to study in that region: at any rate with schoolteacher parents, it is likely he was introduced early to the wonders revealed by the microscope – a widespread theme in Victorian English education. Whatever the case, his first recorded venture into mounting was a series of polariscopic slides presented at a soiree of the Midland Counties Chemists’ Association on December 16 1875. These were of various starches: four slides of this kind are illustrated below, including one sold by Amadio (none are dated, but the Amadio address indicates a probable early 70s slide).

Slides probably made in Hume's early Gloucester days

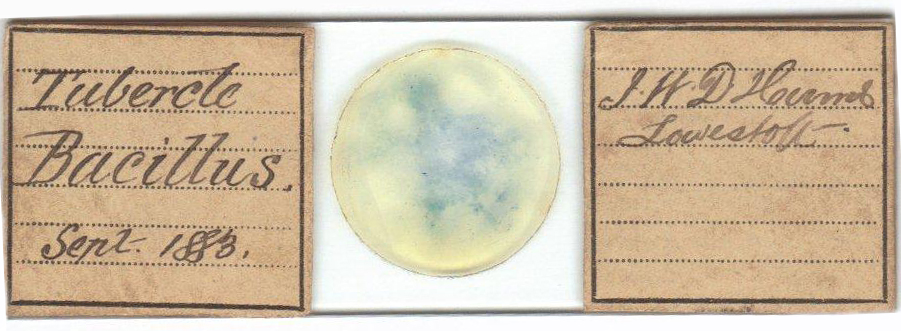

In 1879 he moved back to the other side of England, to Lowestoft. The 1881 census shows him well established at Alexandra Terrace, 27 Clapham Rd., Lowestoft, with his wife, two year old son Ernest, a domestic servant Sarah Plant, and a surgeon, John C. Creswell, as a boarder. Creswell was triply qualified as surgeon, physician and apothecary, and in the last category he and Hume may have collaborated. For a pharmacist, he seems unusually au fait with bacteriological methods, and must have kept abreast of the literature, since the Ziehl-Neelsen sputum stain shown here was done within a short time of the method’s publication.

A Ziehl - Neelsen stain, prepared within a short time of the method's publication.

By the 1891 census Hume had moved to 48 London Rd., Lowestoft, now with a daughter, Gertrude aged 8, a new domestic servant, Jessie Wilson, and his son Ernest, now also qualified as a pharmacist. The household also included a spinster lady, Christiana Norris, boarding with her companion Mary Bridges. His business was listed by the Royal Pharmaceutical Association as The Grove Pharmacy. The move was a good one: Harrod’s 1877 Directory reveals London Rd. as a veritable Lowestoft mini Harley Street. Among Hume’s professionally valuable near neighbours were a physician/surgeon at no.10, another at no.57, a chemist’s assistant boarding at no.11 (who in all probability was working for him), a surgeon/dentist at no.28, a chiropodist at no.81, and a surgeon at no.84. An even more interesting neighbour, in view of Hume’s mounting activities, was a taxidermist in a nearby street. Hume’s immediate environs in London Rd. boasted many affluent households – occupants included bank managers, clergy, accountants, and many prosperous merchants. Households commonly had servants, cooks and nurses, and at least one had a butler. A pharmacist would have prospered. By 1901, still at no.48, Hume had no boarders, but yet another new servant, Agnes Plisborough. Next door at no.50 there was an uninhabited house, frustratingly recorded simply as “shop”, which may well have belonged to him. (Trade sections of directories list him at no.48, but do not mention no.50.) He did not remain unopposed in business: Boots, then already an aggressive conglomerate, are listed in Kelly’s 1900 Suffolk Directory with premises at 106 London Rd. (they remain today, at no.76a).

The move to Lowestoft again poses questions: he may have been prompted by an advertised business opening. Demographic data however indicate a large focus of Humes in north eastern Yorkshire, with a scattering down the coast into East Anglia, so there may have been family commercial contacts. While the 1901 census has him at London Rd., by 1911 he had moved to 38 Kingsholm Rd., Gloucester. That move was almost certainly prompted by concern over Annie’s father Alfred, who by the 1911 census was a retired 91 year old widower living in Nailsworth, a country village some miles from Gloucester. The 1901 census shows Alfred as an auctioneer, who had by then moved from 16 to 31 Worcester St., and may reasonably be assumed to have owned several properties. John and Annie Hume’s new house in Kingsholm Rd. was probably owned, or managed, by Alfred: Kingsholm Rd. is the continuation of Worcester St., familiar territory for all concerned. John Hume died there on May 16 1912. Evidently he was a “high” Anglican, since memoria were observed for him by the Guild of All Souls, which he probably joined while in Lowestoft, via its Walsingham Chantry in Norfolk. On his death, his estate was valued at 5,002 pounds 8 shillings, a tidy but not excessive sum.

Hume felt confident to exhibit slides at the soiree of 1875: this was not his first exercise in mounting – the Amadio slide is probably earlier, and a butterfly wing slide was made on 20th February of that year. With such an under documented mounter, slide dating is difficult, unless labelled with evidence.

His west country connection was not only with Gloucester, since the Bath Microscopical Society owned at least one example of his work, and probably more. No record exists of Hume being a member of the Quekett Club, but he may have belonged to the Bath Microscopical Society.

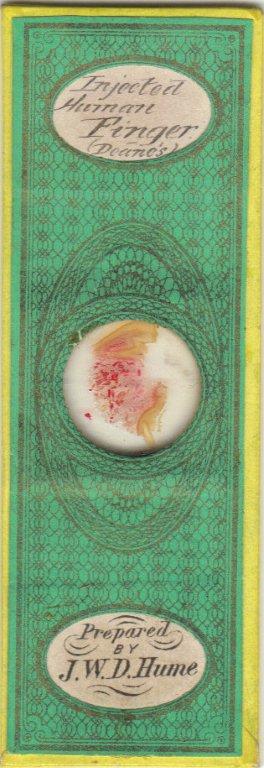

More evidence for Hume's clinical connections - a probable amputee specimen. "Doane's" may indicate the patient or the surgeon, and the name Doane has strong Gloucestershire association. Unfortunately not a dated slide. Hume may have been a member of the Bath society, and visited there when returning to see his Gloucester in-laws.

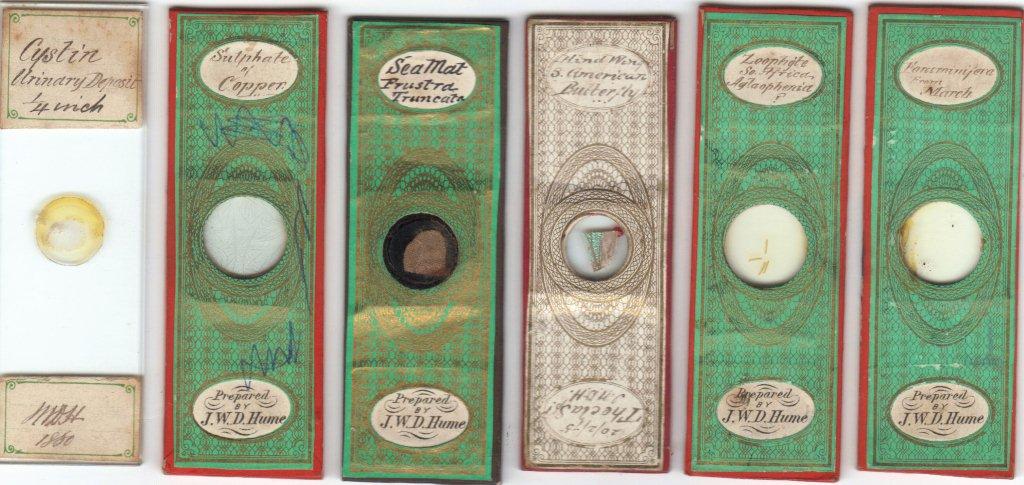

Any idea that Hume confined his interests to the starchy vegetable kingdom is dispelled by slides with wider subject matter, such as the foraminifera, zoophyte, sea mat, butterfly and chemical subjects shown below.

Non botanical preparations. The chemical slides were naturally interesting to a pharmacist, and the urinary slide probably reflects Hume's clinical involvement.

Was Hume a professional mounter, as suggested for instance by Bracegirdle’s Microscopical Mounts and Mounters? The definition is problematical. If the term defines principal occupation, Hume was not “professional”, having spent his entire career as a working pharmacist. But was his mounting activity commercial, and if so, how extensive was his business? The existence of duplicate preparations, as illustrated in Bracegirdle plate 21 O & P, suggests sales of slides, and he certainly, when young, had sales via Amadio, as illustrated. Many starch slides are likely early work, to supplement his income (if any!) as an assistant chemist. Hume slides rarely turn up for sale on internet sites such as eBay, indicating, perhaps, a comparatively modest output overall. I’ve never seen a secondary Hume label on the slides of others – in contrast to, say, the Maidstone dentist Rogers, who had a clinical business and a commercial slide outlet within a few metres, which on-sold slides by many preparers, bearing the Rogers secondary label. Possibly Hume earned fees for diagnostic work, witness the TB sputum slide. Proximity to several Lowestoft clinicians strengthens that possibility, and he also may have had paid hospital connections (Lowestoft hospital authorities ignored my queries). On evidence quoted here, questions on “commercial” remain only partially satisfied. The definition of expert, however, is beyond doubt.

Finally, a clinical footnote. Hume’s slides are classic illustrations of increasing handwriting size with advancing age (like those of Amos Topping, and a caveat when attempting to ascribe slides to particular preparers). Ceteris paribus, presbyopia is the likely diagnosis.

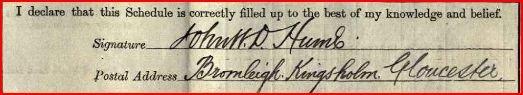

Hume's signature not long before his death, from the 1911 census.

Comments to the author will be welcomed.

Acknowledgements:

I am much indebted to Brian Stevenson, for his unstinting help with information, particularly with Google Books details, which yield comparatively little to us antipodeans, and to Brian and Howard Lynk for much useful discussions. Thanks also to Julie Wakefield of the Royal Pharmaceutical Association, and to John Welsh of the Seamer Parish Council, for their help.

Sources:

B. Bracegirdle, 'Microscopical Mounts and Mounters', Quekett Microscopical Club, 1998, London,

Royal Pharmaceutical Association (UK) archives

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the April 2010 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .