|

|

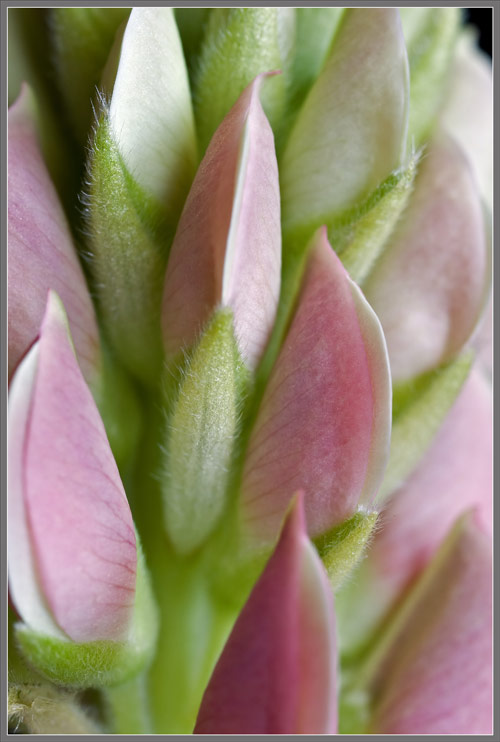

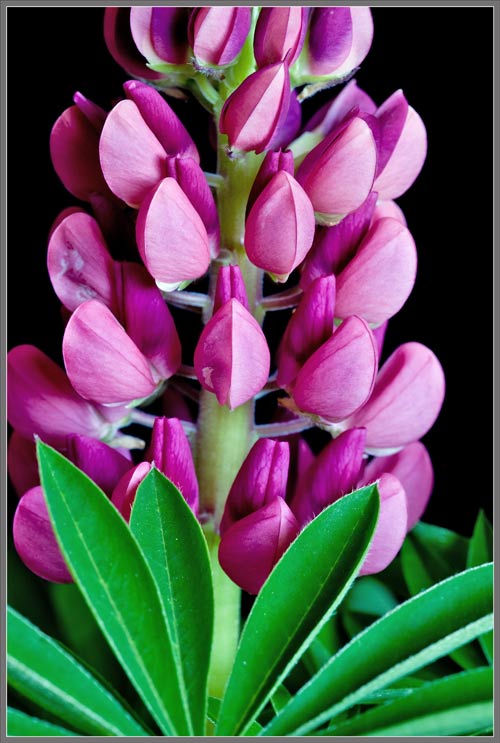

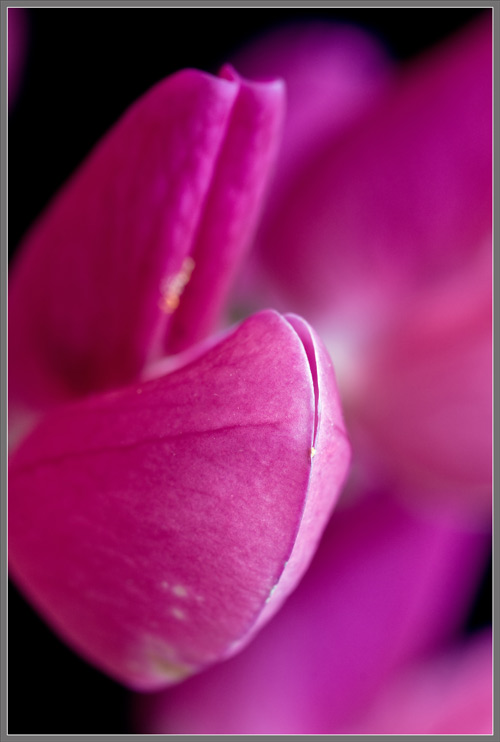

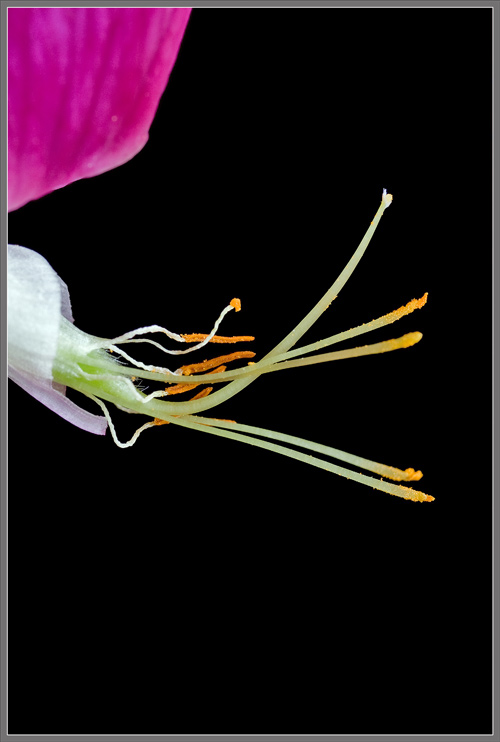

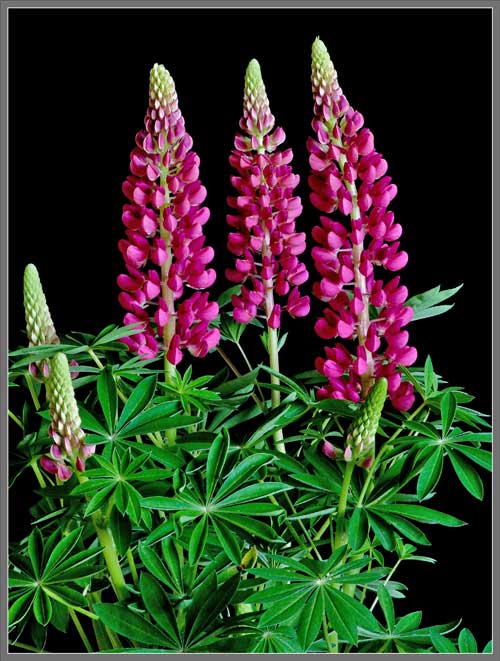

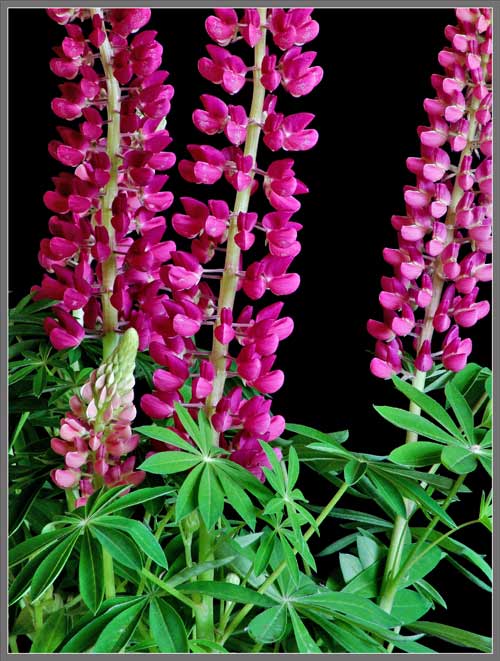

A

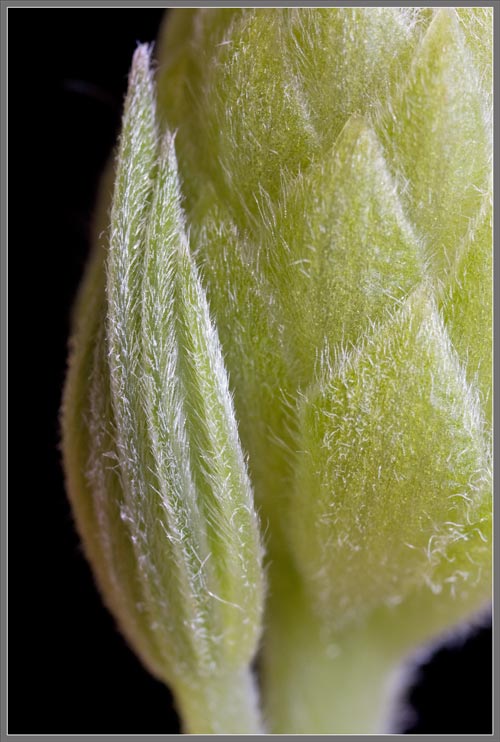

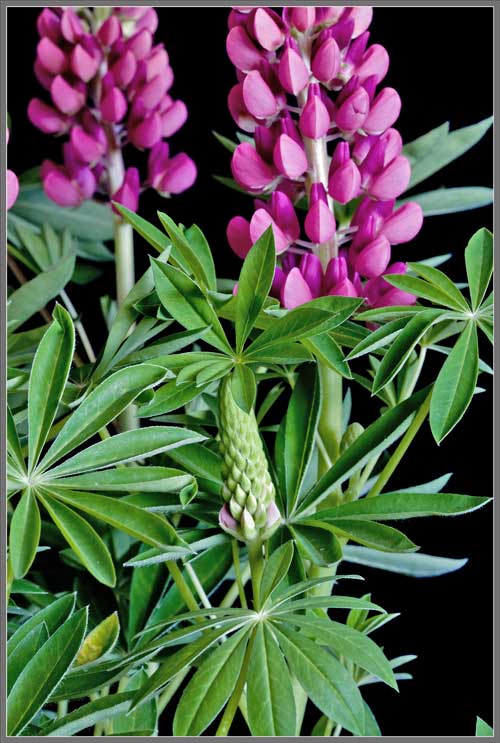

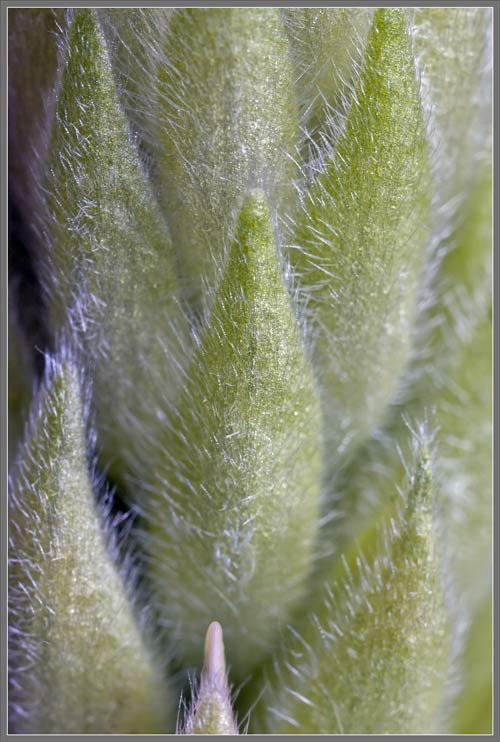

Close-up View of a Second Lupine Hybrid

|

|

|

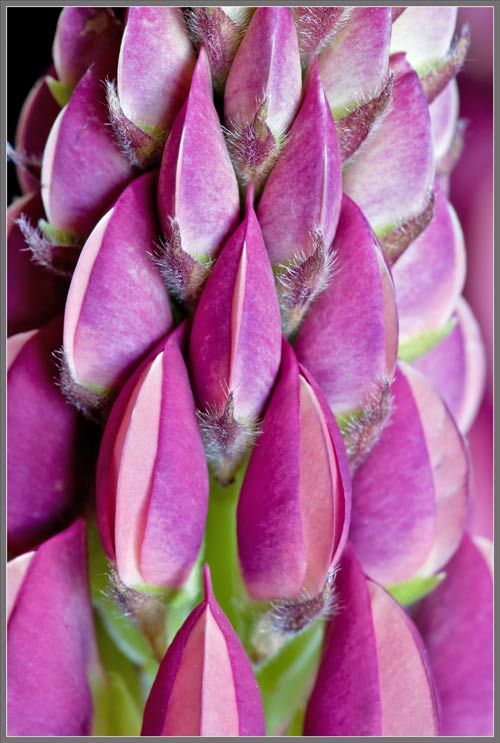

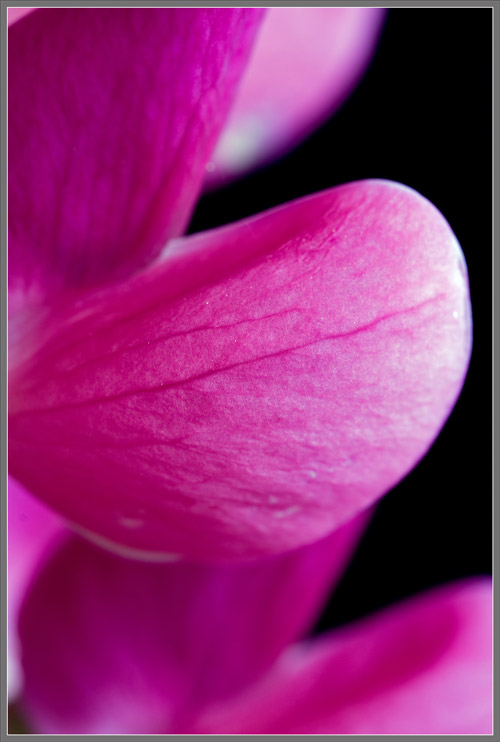

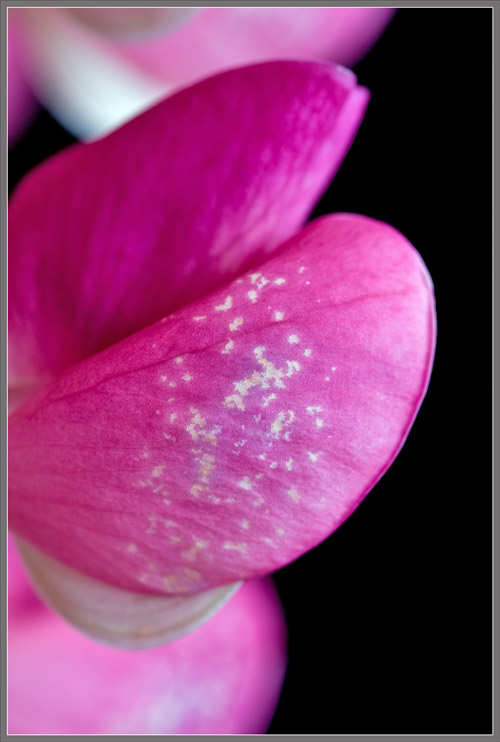

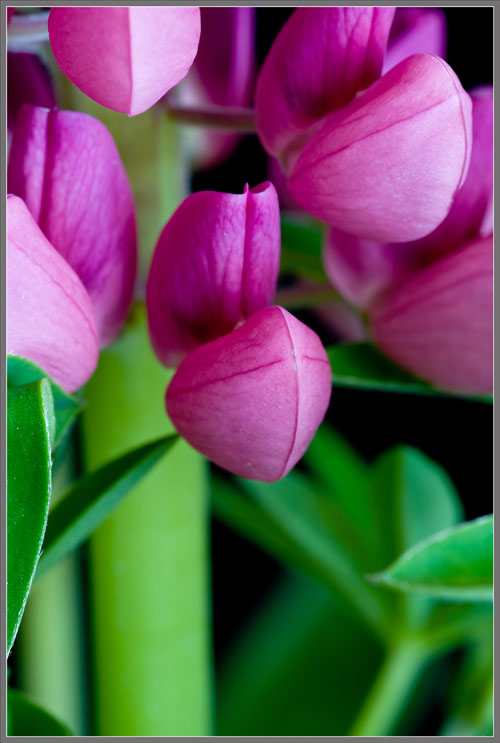

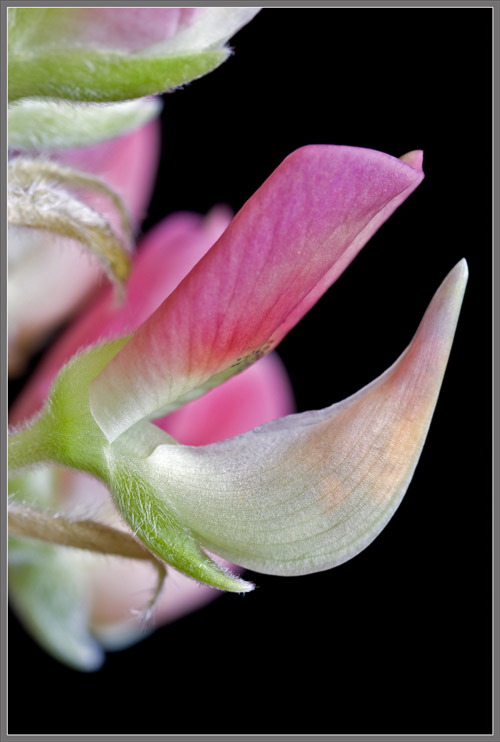

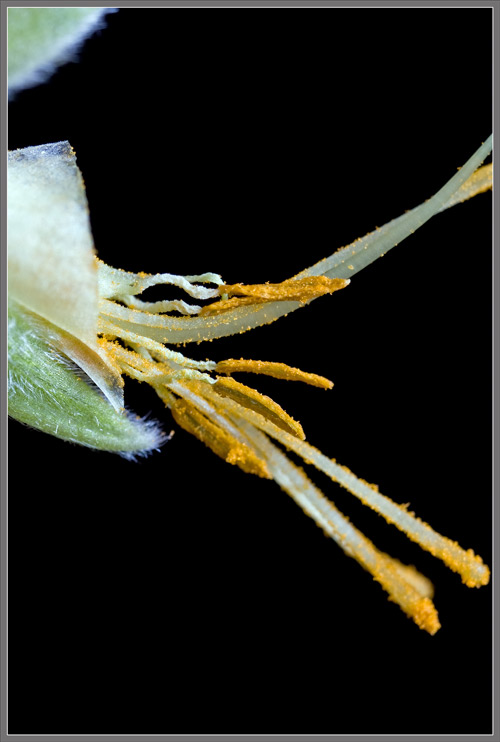

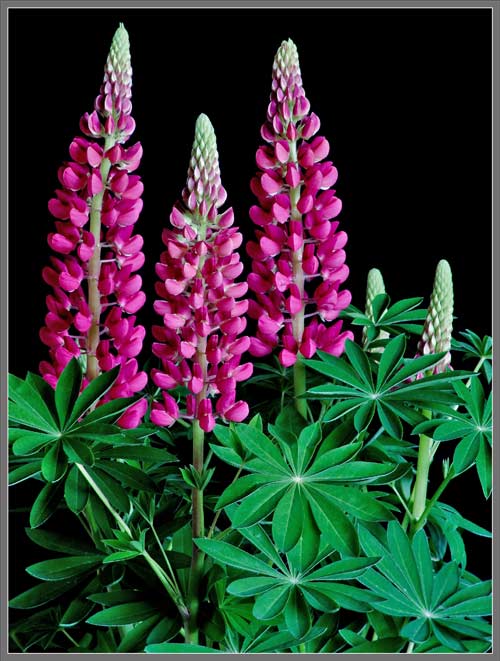

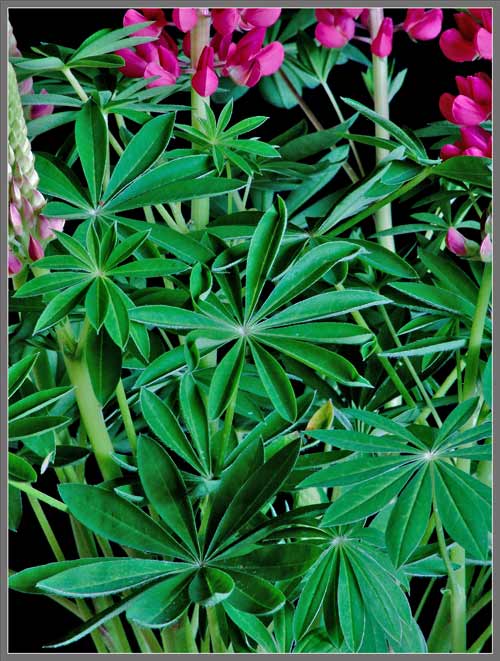

A

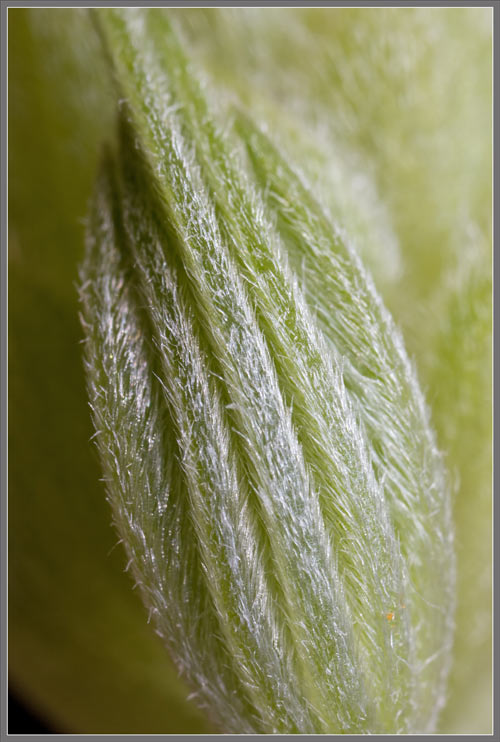

Close-up View of a Second Lupine Hybrid

|

Published in the

April 2012 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web

problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .