|

WHAT PRICE OPTICS? Frithjof A.S. Sterrenburg Heiloo - The Netherlands |

In the quest for quality, microscopists tend to yearn for the most modern and perfect optics such as the planapochromats offered by the major manufacturers. I will not belittle their performance, but it cannot be denied that their price—well into the four figures—may be daunting. So what concessions do you make if you have to use less expensive objectives?

Brand and performance

I use a variety of stands and lenses for both quickly screening samples for diatoms and publishing on the latter in professional journals. In most cases, I have noticed that interesting fine details eventually photographed in DIC with costly objectives had already been visible when I screened the samples in ordinary brightfield with objectives of more modest performance—sometimes with a bit of oblique lighting. That, after all, was the reason why in the end I decided to record those details in DIC!

I therefore am not very happy with the policy of journals that the light-microscope(s) used for the study be specified as regards brand and model under the “Methods and Materials” section traditionally forming a part of research papers. With the high and constant standard of quality of light-microscopes produced by renowned manufacturers in the past several decades, the methodology of the research is not influenced by whether you use optics of manufacturer A, or those of manufacturer B. The specification is non-informative as it would be highly unusual for a result to be reproducible exclusively if you use equipment of company A, for instance. An exception would be a study using certain advanced optical methods such as Jamin-Lebedeff interference contrast, where the aspect of the image is indeed dependent on the technical parameters of the instrument.

Technical conditions

I therefore decided to take photographs under completely identical conditions of a suitable test object with oil immersion lenses of 90-100x power and numerical apertures of 1.3 to 1.4, of very different manufacture and vintage.

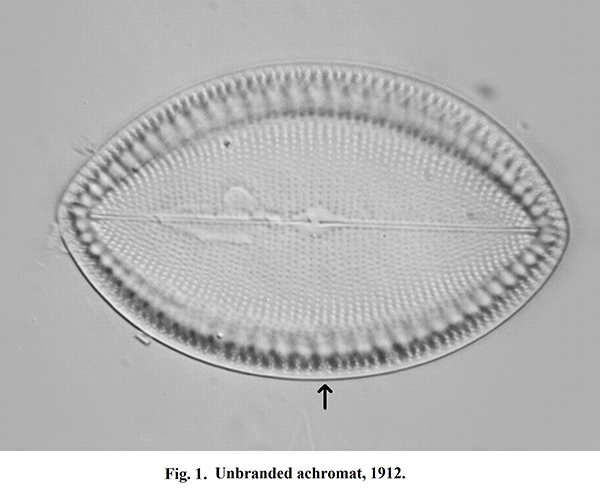

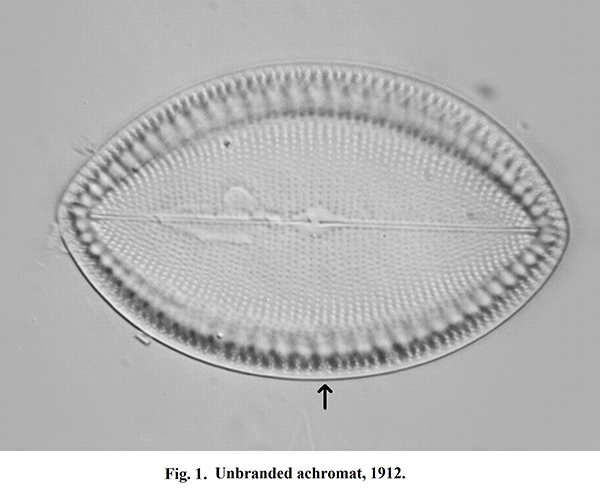

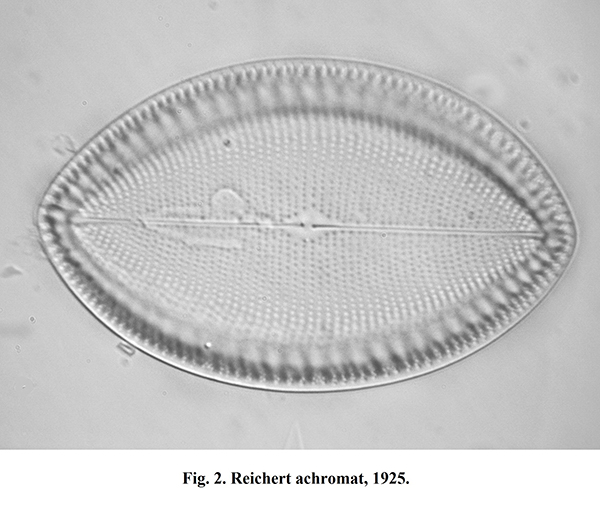

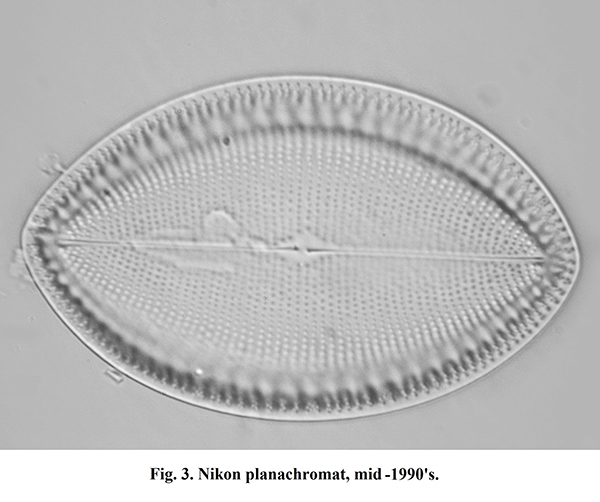

The test object is a marine Cocconeis species mounted in naphrax. It is not a very difficult diatom to visualize, but neither is it very easy and thus it is representative of the great majority of diatoms one is likely to encounter. Its contrast is average, DIC or phase-contrast are not necessary, and although its overall structure is only moderately fine, at the margin of the valve there are clusters of much finer “dots” that are not at all easy to resolve. Diatoms are, of course, a much more critical test object than stained smears or sections as in the latter case contrast is far higher.

Illumination was with white light, unfiltered. In this manner, the residual chromatic aberration and the difference between achromats and apochromats should become maximally visible. The condenser was an achromat-aplanat of NA 0.95, with iris always fully open. Illumination was by a strictly central full cone of light so that there was no contrast enhancement.

The camera was a 10 Mp model, set at monochrome as this is the standard for scientific publications on diatoms. No image processing except for slight cleaning of the background has been used. There are minor differences in focus settings but they do not affect the comparison. In the first image, I have marked a particularly fine cluster of dots at the margin that forms the best criterion for comparison. Also, the size of the diatom differs slightly in the pictures as the magnification of objectives has not always been exact.

The lenses

Figure 1 was taken with an unbranded achromat of NA 1.3 made around 1912. Especially around Wetzlar, Germany, there have been many small cottage-industry manufacturers of microscope optics “for the trade” as it is called—OEM as we say now. Traders could order them with their firm’s name engraved; I have examples called “Elga”, for instance, and the pre-war German “Kosmos” microscopes probably used them also. This specimen only tells you it’s an Oel Immersion 1/12, but it is still in excellent condition.

Figure 2 was taken with a Reichert achromat NA 1.3, vintage 1925, brass and chrome mount, in mint condition. I’ve had this for ages and it has always been a favourite because of its crisp images.

With Figure 3 we enter modern times, a Nikon planachromat 1.3 of the mid-1990s. It has about double the number of lenses as the previous two objectives to obtain a flat field, but for diatoms that is unimportant as they themselves are almost never “flat”.

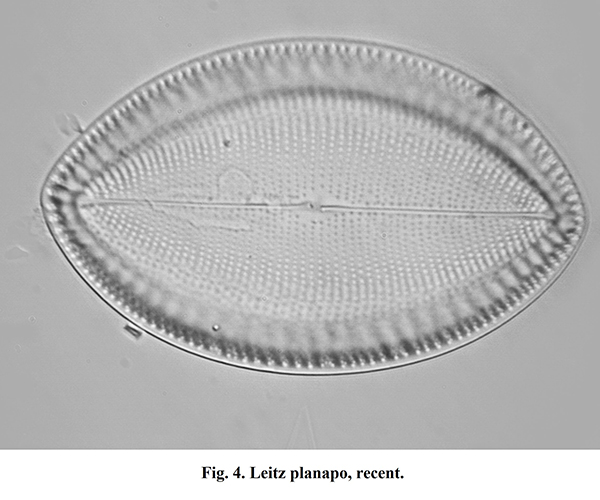

Figure 4 closes the show, a modern Leitz planapochromat NA 1.4 in the Olympic price bracket. Again, its very flat field offers no advantages here but it ranks among the most highly corrected optics available.

So what?

Considering that there lies about a century of optical technology between Fig.1 and Fig. 4, with a current price difference of circa 1:100, the difference in image quality is not really spectacular. It would have been even smaller if the achromats had been combined with a green filter. For some exceptionally difficult diatoms like extremely finely structured Nitzschia or Amphipleura species, the modern objectives would probably show a more marked edge over the ancient brass lenses, especially with a “wet” condenser. However, the oldies—if in mint condition—could safely be used for some 90% of the illustrations of diatoms in the scientific literature without anybody noticing.

Brass objectives resemble steam engines: with proper care, they last forever. Most objectives I have seen that were affected by the dreaded delamination were manufactured in the Sixties or Seventies !

All comments to the author Frithjof Sterrenburg are welcomed.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the April 2012 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .