|

Practicing Scales by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

When I was 6 years old, my parents decided that I should take piano lessons. This was, in part, because I was a very active child; even my first grade teacher wrote on my report card that I “tended to talk too much.” Perhaps that explains why I became a university professor. Today, I probably would have been diagnosed as having Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and given regular doses of ritalin which to the layman such as myself, seems counter-intuitive since it is a stimulant. Oh well, I escaped that fate and got piano lessons instead. My mother had been at a garage sale and bought an old upright piano for $5.00 and had it put out in the garage. That was a not insignificant amount in those days being the equivalent of about $65 today. It was in poor condition, both physically and musically. To get around the first, she painted it white and because of that it became known as our “White Elephant” as it was taller than I was. My mother also found someone to come and give it some musical therapy (that is, tuning). A teacher, Miss Christiansen, was found who lived only about 10 blocks away so that I could walk over to lessons. As you might expect, the very first task given to me was to learn scales and then work on a few nauseatingly saccharine little “children’s pieces”.

I would go out each afternoon after school and pound the hell out of that old piano. However, I only got to release a lot of energy and didn’t end up annoying anyone since my mother, father, and grandmother (who lived with us) were all at work and my younger sister was with a baby sitter. The nearest neighbors were also at work so, in the end, I began browsing through the book of “Collected Pieces for the Beginner” and found a little Bach prelude to which I took a liking and began to practice it seriously, but in secret. I decidedly didn’t want anyone to know that I was enjoying any aspect of this undertaking. Each lesson with Miss Christiansen would, of course, begin with scales and more scales, and then some monstrosity like “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” which I, to this day, detest, even in the version of the Mozart variations.

Playing scales taught me 2 basics: 1) that it improved my playing and my general sense of discipline and 2) that, despite the praise of relatives and friends, I could never be a first-rate pianist. I had the passion, but not the intuitive spontaneity necessary for truly great playing.

In my early teens, the family began taking a vacation of a week or two to Minnesota to go fishing and this was my first encounter with scales of a biological nature. My father was a fine cook–running a café taught him that–but, he was not enthusiastic about gutting and cleaning the fish, so he taught me. I suppose that was my first experience of “dissecting” something as well as learning a bit about scales. I was curious about the internal part of the fish and soon started poking around in the intestinal material looking for parasites. The lakes were full of copepods, freshwater shrimp (Gammarus), water beetles, hellgrammites, and, of course, fish. I used to elicit gasps of disgust from my mother and sister by collecting large black leeches which would attach themselves to the sides and bottom of boats.

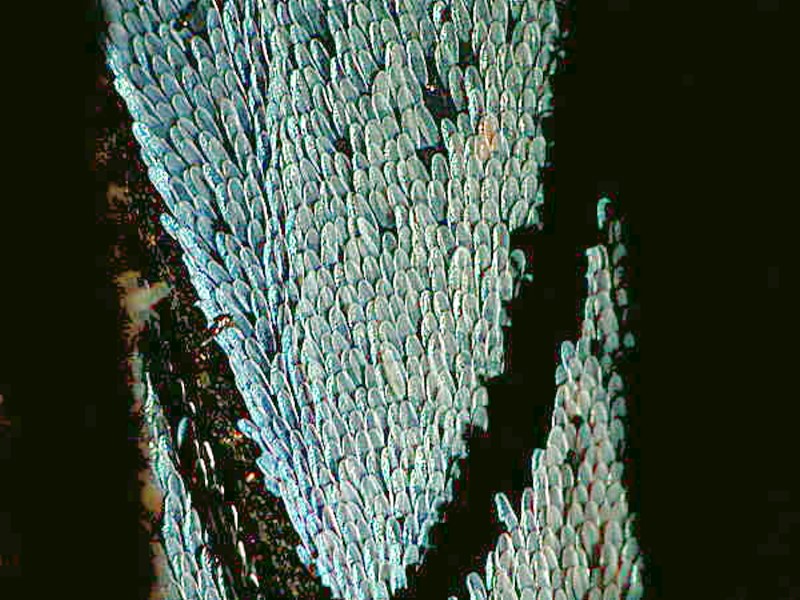

We almost always caught enough fish that we could ice some and bring them back home–500 miles away–and pop them in the freezer. This meant that I had easy access to scales to examine with my microscope. Scales are highly complex and come in a remarkable variety of shapes and sizes. They are genetically derived from the same types of genes that produce hair and teeth and their composition can involve both mineral and organic material. The four common types are Cycloid and Ctenoid which are found in most of the bony fishes, Placoid found on rays and sharks, Ganoid on gars and sturgeon. Examples of the different types can be seen here:

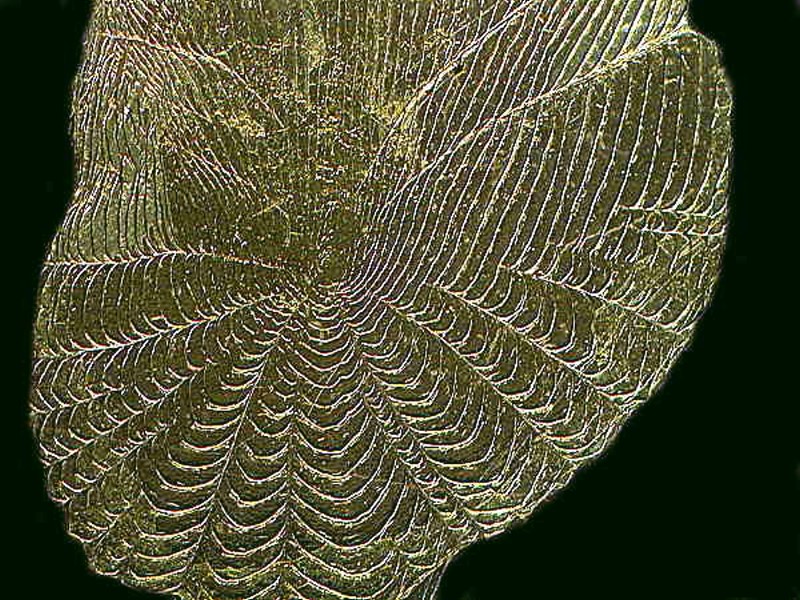

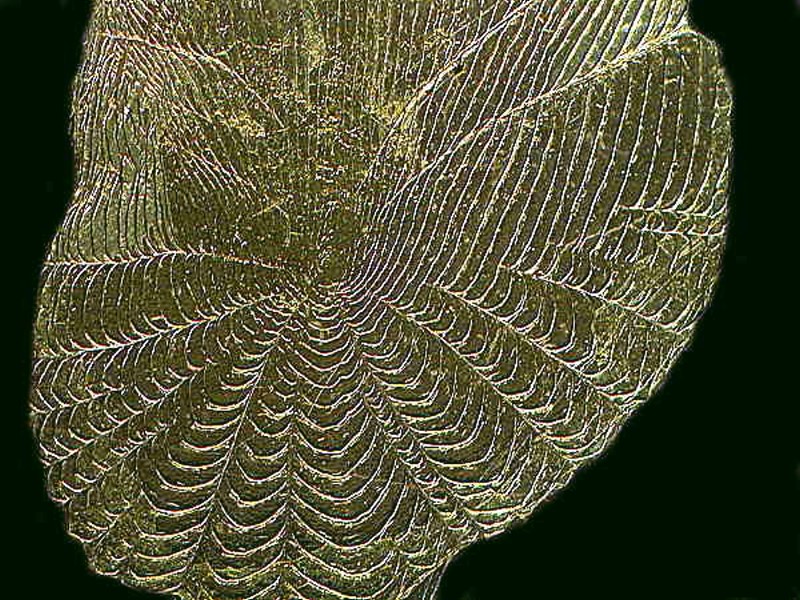

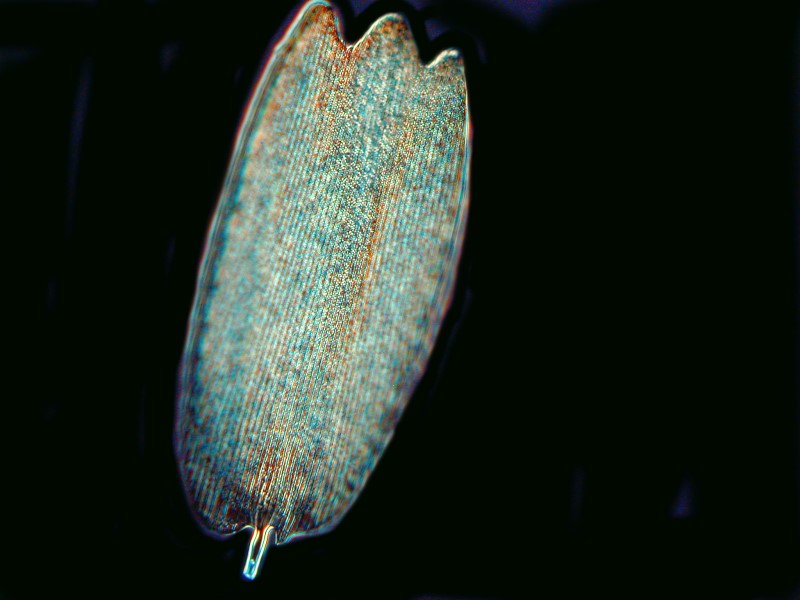

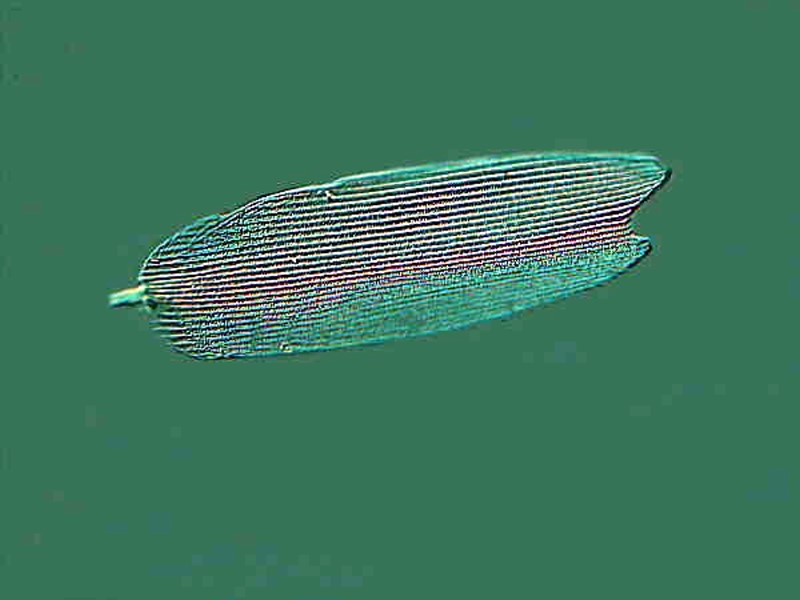

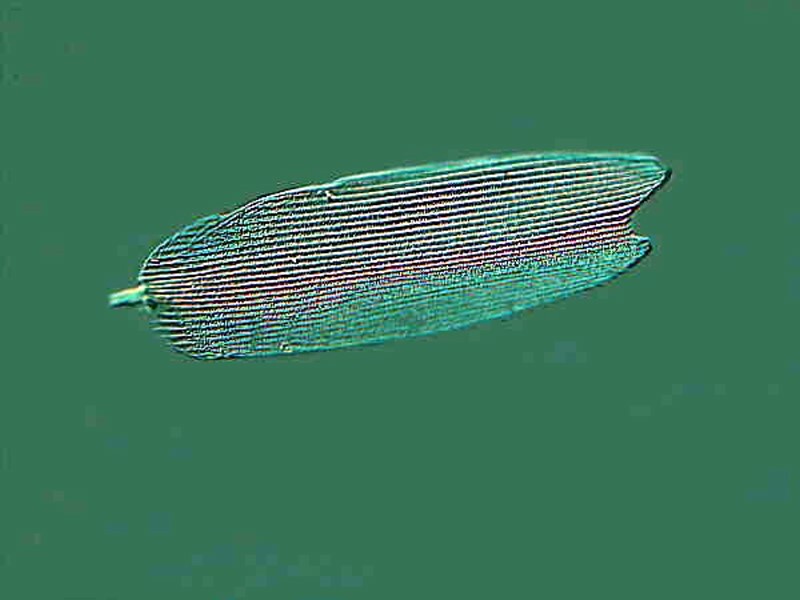

And I’ll show you a couple of closeups; first a cycloid scale and then a ctenoid one.

As you can see there are growth rings and a question arises: Can these be used to determine the age of a fish? The answer is interesting and complicated (Mother Nature is jealous of her secrets). Fish biologists use a variety of techniques and structures and scales are certainly one measure, but they also examine fin spines, teeth, bones, and otoliths which are those odd calcareous structures found in the middle ear.

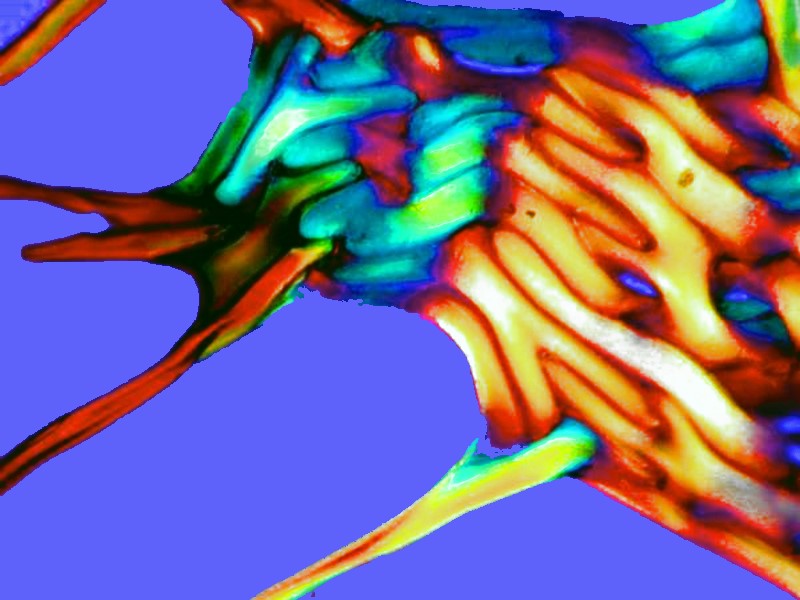

In the vast majority of fish the scales form overlapping patterns which vary significantly from species to species. Below are 2 examples.

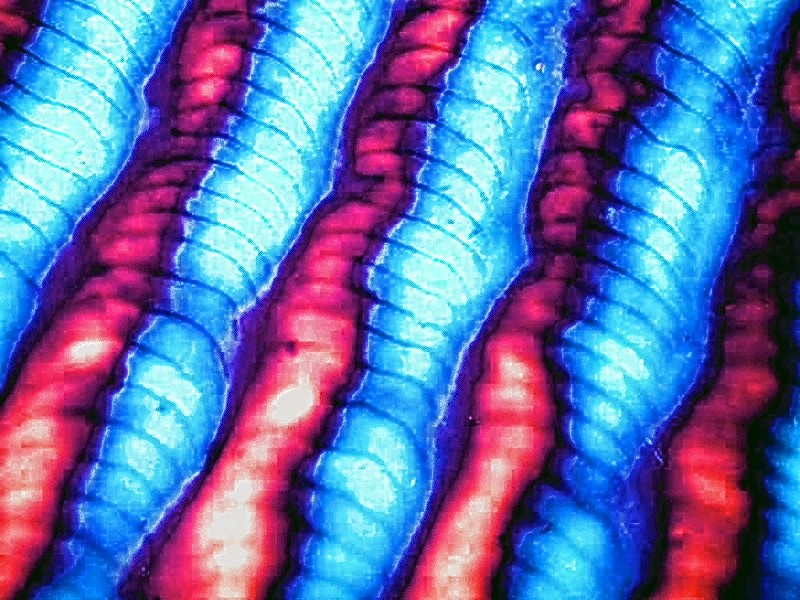

Many scales are birefringent and you can see an example below.

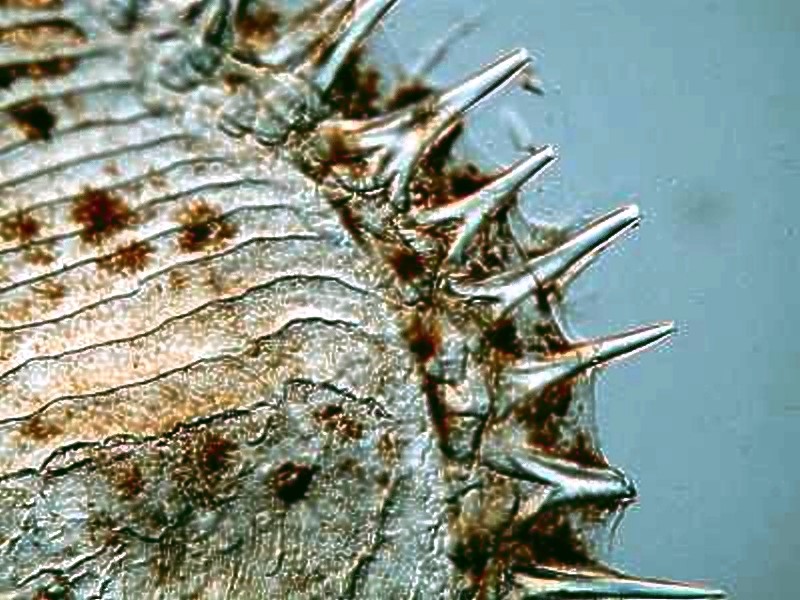

Patterns may be the rule, but as we would expect, there are exceptions. A notable one is to be found in the batfish.

Notice the distinct “bumps” in the epidermis; these are the scales and when isolated, they look like small bits of coral as you can see here:

Also, we generally think of fish scales as small, flexible and translucent, rather like a bit of plastic. But, of course, Mother Trickster presents us with something sizeable, opaque, and brittle in the scales of the Amazonian Piracuru arapaima. These are harvested and isolated, cleaned and sent to shops that sell aquatic curiosities and are often sold as finger nail files.

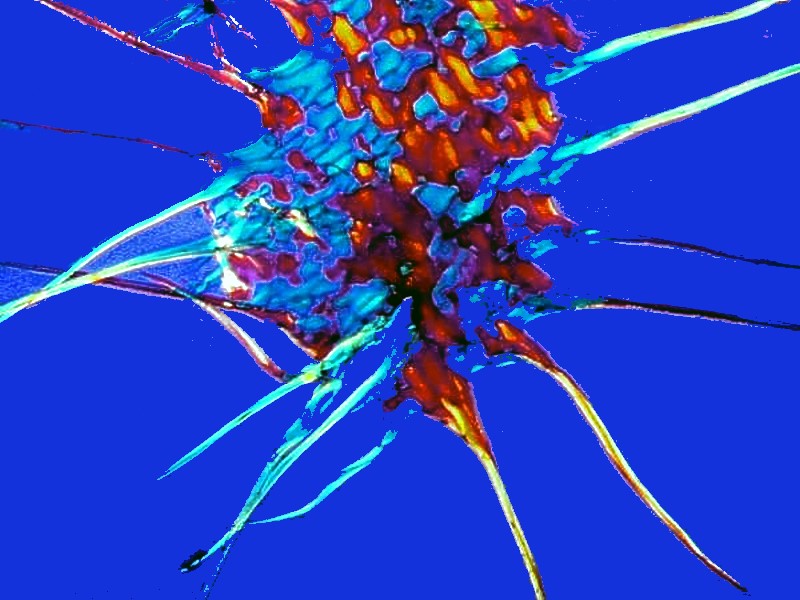

Shortly before we began taking a vacation in Minnesota, my parents had moved; they bought a larger house and a large old upright Ivers and Pond piano which was an extraordinary improvement over the “White Elephant” and I began to practice more seriously. At the back of the property was a dense lilac hedge and behind that an alleyway where wild carrot plants grew in profusion. There, on those plants, were large caterpillars of the Eastern black swallowtail butterfly. I collected some along with the plants and put them in large jars with holes punched into the lids. I was delighted to watch them form chrysalises and then emerge and pump fluid into their wings. I kept two as specimens which I anesthetized and killed with carbon tetrachloride. In those days, you could buy bottles of it at the local drugstore; apparently nobody had quite realized just how toxic it is. The other butterflies which hatched, I released. This was my second discovery of biological scales. I noticed what appeared to be a fine powdery dust on my fingers after handling one of the preserved ones and upon looking at this “dust” under the microscope, I was astonished to see enormous numbers of tiny scales. Here are 2 views of single scales.

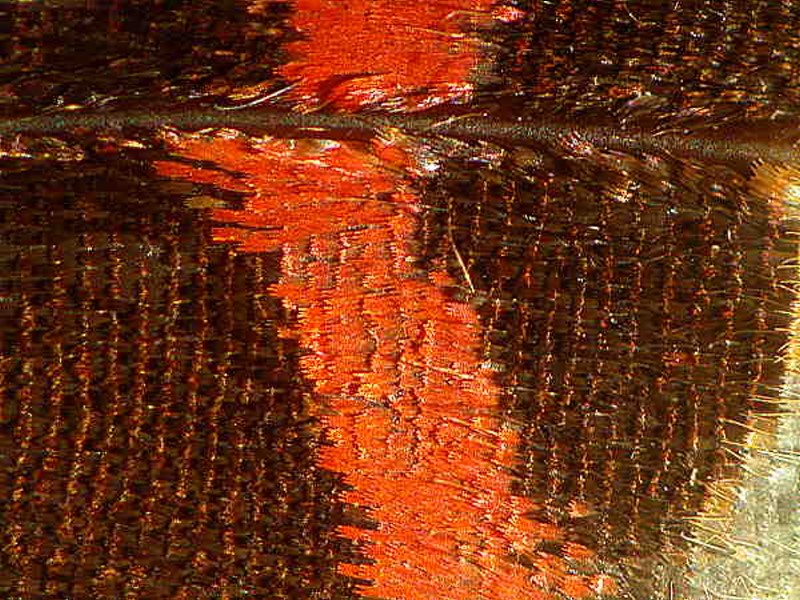

On a single wing, there is enormous variation in the coloration and patterning as a consequence of the arrangement of the scales. Below are two images both of the same wing, but of different areas.

These are of a butterfly from India, Graphium sp. Note that in addition to the scales, there are many tiny sensory hairs or setae. Scales are, in fact, actually modified setae.

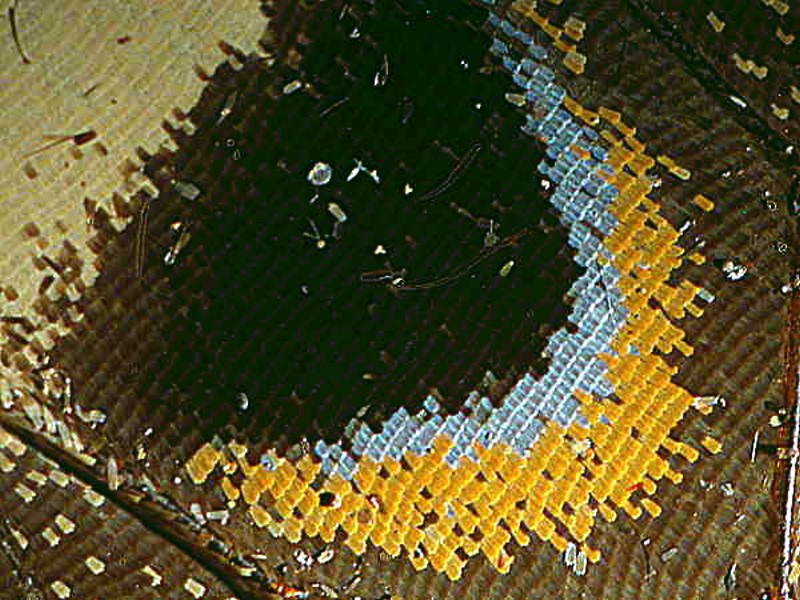

In a number of wings, one finds patterns that form what a potential predator may well interpret as an eye and be thereby deterred from attacking. Here is an example from an area of a wing of Papilio demodocus.

Some scales are highly iridescent and in this specimen of the African butterfly, Salamis cacta, we can clearly see that this very pleasing pattern would make a quite attractive fabric pattern. Here again, we can also see setae.

Earlier I mentioned the veins in the wings and there are certain patterns of venation, but these are by no means fixed and vary considerably. Now lets go back and look at a single scale again. Note the little extension on the tip on the right side.

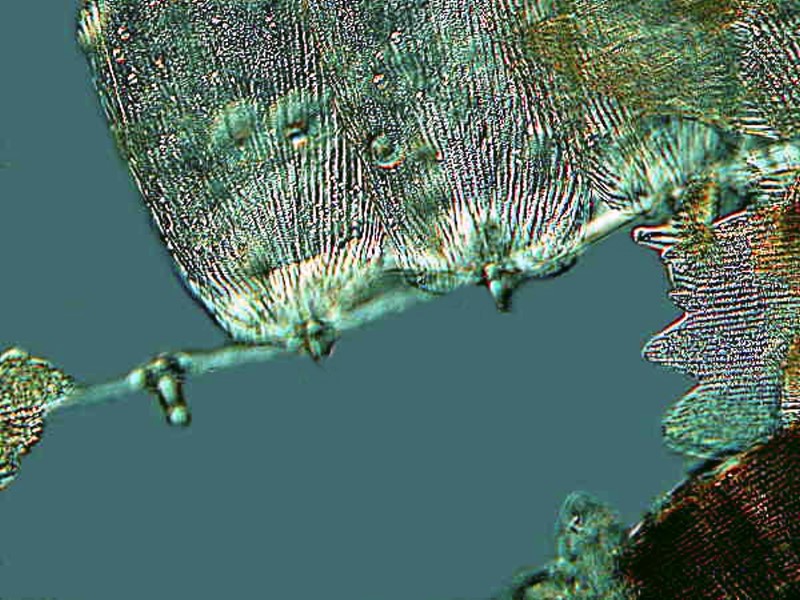

Here we encounter a quite amazing piece of morphological engineering. I will show you 2 views which reveal how scales are attached to the “fabric” of the wing in such a manner that they are easily released thus explaining why if you touch the wing you get “scale dust” on your fingers.

We are seeing a series of “seams” across the wing which has sets of little “pockets” arranged along the lines and into which the tips of the scales fit–an amazing arrangement.

As you can see, there is an enormous amount to investigate regarding butterfly scales and, as I grew up and my piano playing matured a bit, I found the same was true with regard to musical scales. Although, I frankly admit, that I never found myself passionately committed to practicing scales, but I did come to understand the importance of the discipline which they provided. When I was in my late teens, my then teacher, a woman named Miss Kimball, a kind and encouraging soul, cajoled me into giving a recital with her, performing the first movement of the Grieg Piano Concerto as transcribed for 2 pianos. She assured me that I was up to such a challenge, but I was not convinced and on the afternoon of the event, I was petrified. Apparently I got through it without making too many glaring mistakes and the audience applauded, however, that experience convinced me that performing music in public could never be my career. I simply didn’t have the special gifts that were necessary. I came to enjoy playing for myself, my family, and a few of my tolerant friends more after that. I committed myself to being an amateur pianist as well as an amateur natural historian and microscopist entranced by the flashes of color, the weirdness of creatures, the amazing morphological adaptations, the marvels of what can be seen by the manipulation of light, and even at my advanced age, I am still driven my an insatiable curiosity grounded in wonder and astonishment. All of which leads me to my next encounter with scales this time of a botanical sort.

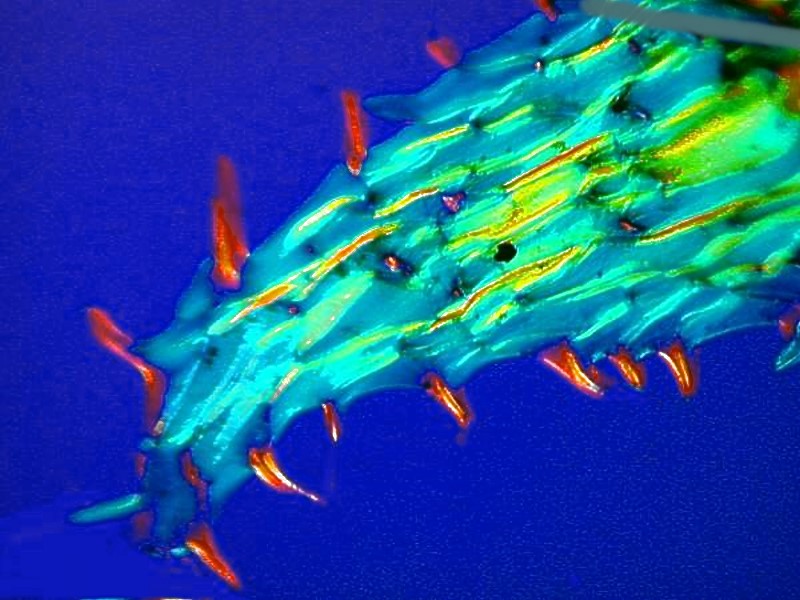

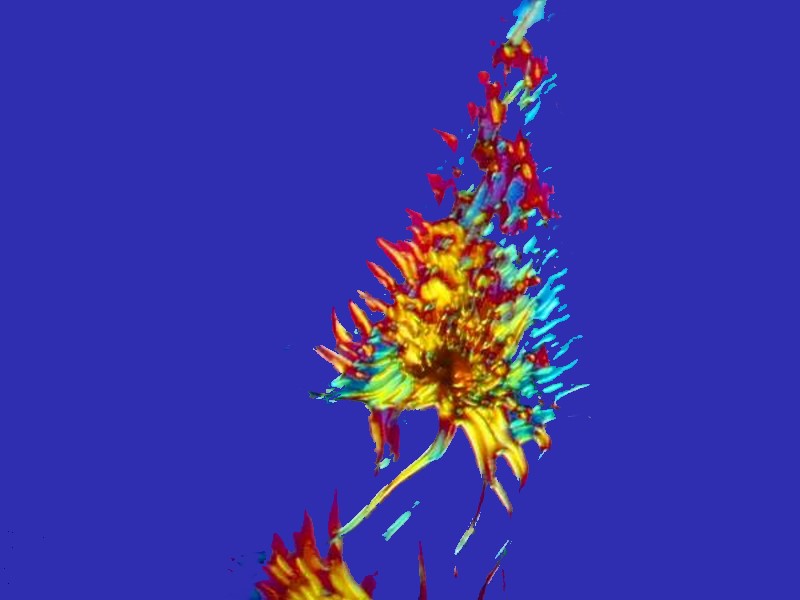

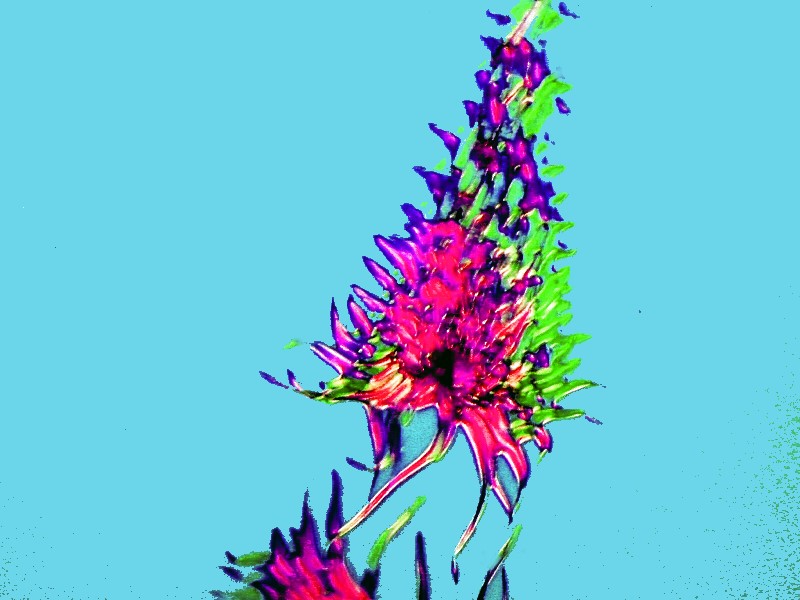

It was a great surprise for me to discover that some ferns have scales and, in fact, scales that under polarized light display great beauty. Here are 2 images of Astrolepsis.

These images and the ones that follow also show the dramatic differences that can be obtained by using different types of compensators.

The next 2 images are of Elaphoglossum.

The next 2 show very dramatically the difference that compensators can make.

The final 2 fern scale images are from an unidentified tropical fern and it looks like it could be a micro-bouquet of flowers.

Well, as usual, I have rambled on and this has gotten rather long. However, there are still other kinds of scales to be investigated which we can do at some later time or which you can tackle on your own. I’ll give you 2 suggestions: there are some fascinating marine worms called scale worms and they do indeed have scales. Also, you might want to look into scale insects; they don’t exactly have scales, but form them on plants and can be a terrible nuisance.

Oh, yes, the piano which I have now is called a medium grand piano, is 5 foot 6 inches and, no, I don’t practice scales anymore.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the April 2017 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .