| There

is indeed much resemblance between our eyes and those of

an octopus. However, a vertebrate eye is formed as an

outgrowth of the brain, while that of an octopus is

formed by an invagination of the ectoderm and a closer

look shows more differences. This is a striking example of

so-called convergent evolution, which means that a

similar organ with a similar function is formed in quite

unrelated organisms. Studying eyes is difficult enough

for an amateur microscopist, educated as a chemist. I am

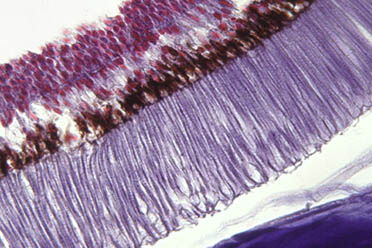

consoled a bit by the essential photochemical part of the

process of the visual process. Armed with books about the

anatomy of molluscs I am trying to understand the

structures I am seeing through the microscope. But

standing before a large sea water aquarium with an

octopus in it, clearly looking at me and following me

with his eyes, I am pondering about what this octopus

really perceives of me. I suspect it must be a lot!

|

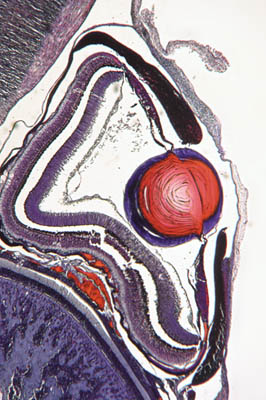

An octopus,

with its large eyes, looking at me. Its eye is white, due

to the reflection of the flashlight against the pigment

cells behind the retina

|