Figure 1. Charles Morgan Topping. From a microphotograph by William Moginie, generously provided by Trevor Gillingwater.

by Brian Stevenson and Howard Lynk

Last updated October 2018

Micscape Editor's note: Mirrored with permission on the Microscopy-UK site from Brian Stevenson's website microscopist.net with the kind permission of the authors.

Charles M. Topping is one of the most highly-regarded microscope slide producers of all time. His work was consistently well-made, from the carefully prepared specimens to the finishing touches. Topping prepared a wide variety of objects, from whole and dissected insects, to stained or injected histological specimens, to finely-ground minerals, to diatoms and other aquatic organisms. From his beginnings in the mid-1830s, Topping’s work was in high demand throughout the world.

Herein we present images of the variety of slides produced by Topping. Many of his preparations include his name or initials. Others are unsigned but can be recognized by his distinctive handwriting. The illustrated examples will help train the reader’s eyes to recognize Topping’s work. Many of these images were previously included in Howard Lynk’s 2018 Quekett Journal of Microscopy paper, “The slides of C.M. Topping - another look”.

Following the slide images, we present a detailed look at Topping’s life.

Figure 1.

Charles Morgan Topping. From a microphotograph by William Moginie, generously provided by Trevor Gillingwater.

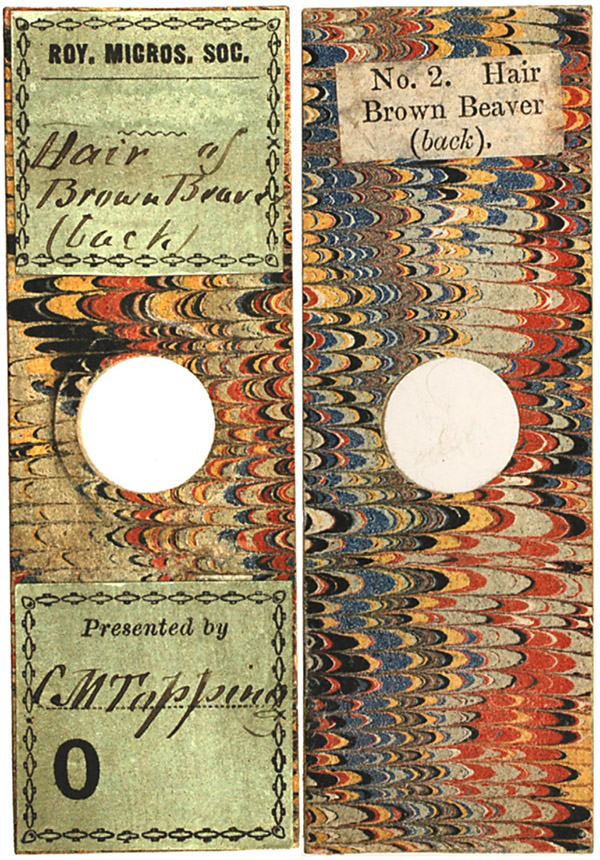

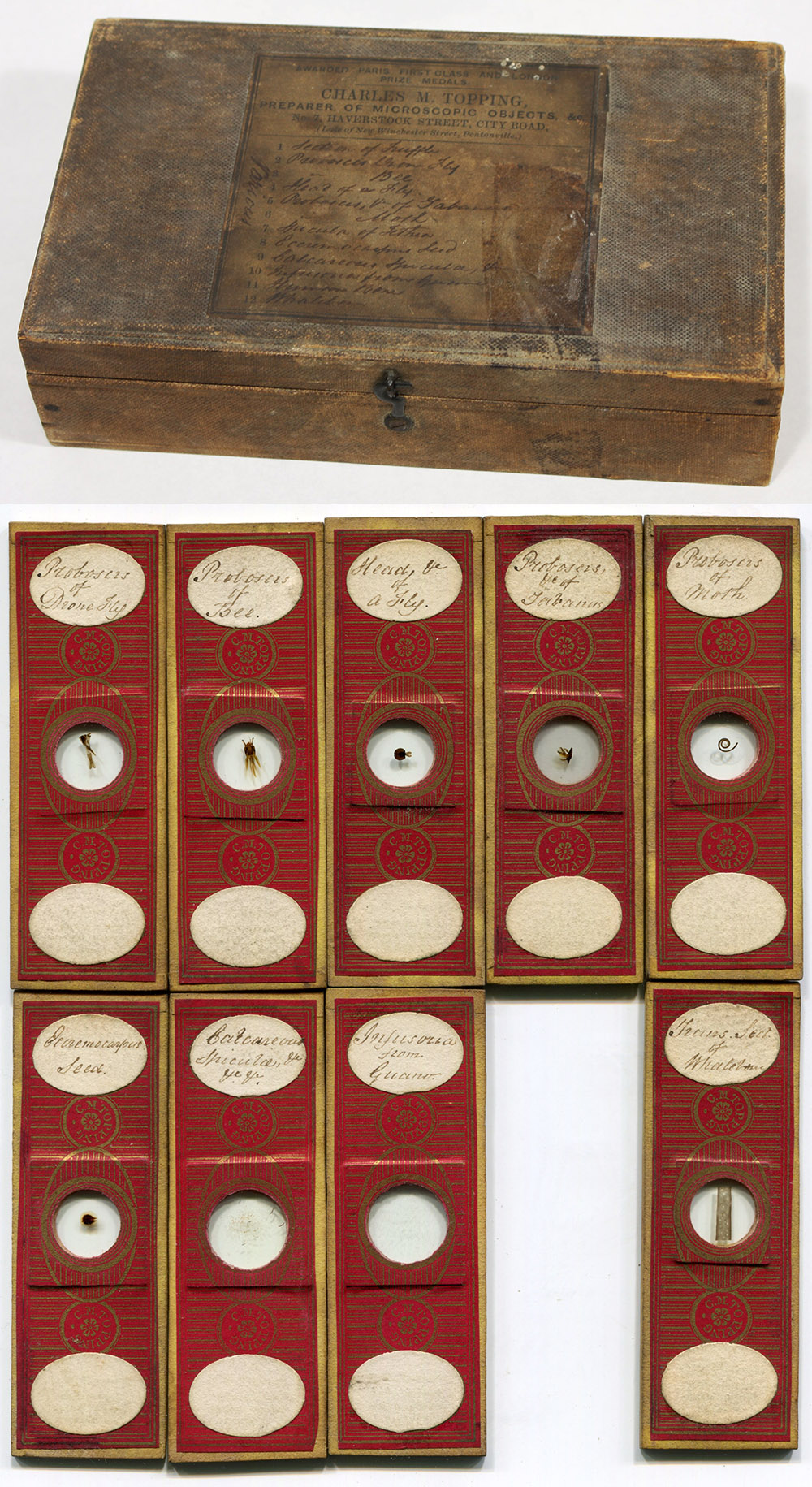

Figure 2.

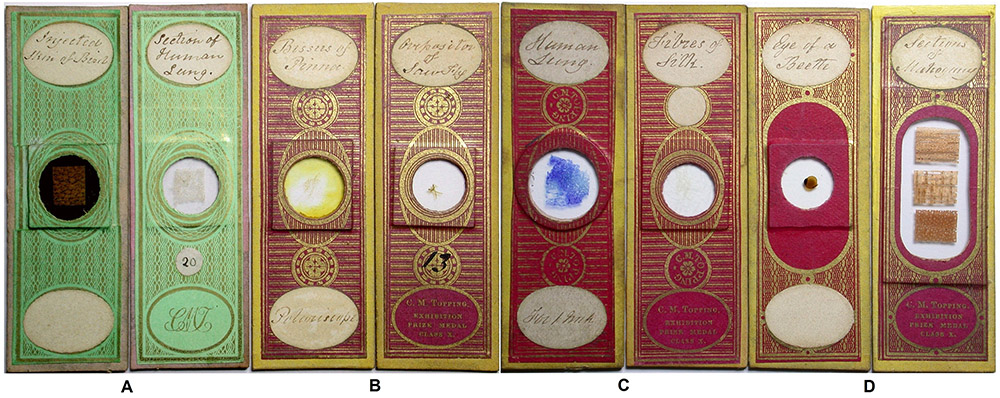

Paper-wrapped slides by C.M. Topping, with the papers that are most familiar to collectors. The green covers (A) were likely introduced in the late 1840s, with the three forms of red papers (B-D) probably coming into use during or immediately after the London Exhibition of 1851. Note the differences in the circular “medallions” bordering the three types of red papers: C includes Topping’s name, while B and D do not.

Figure 3.

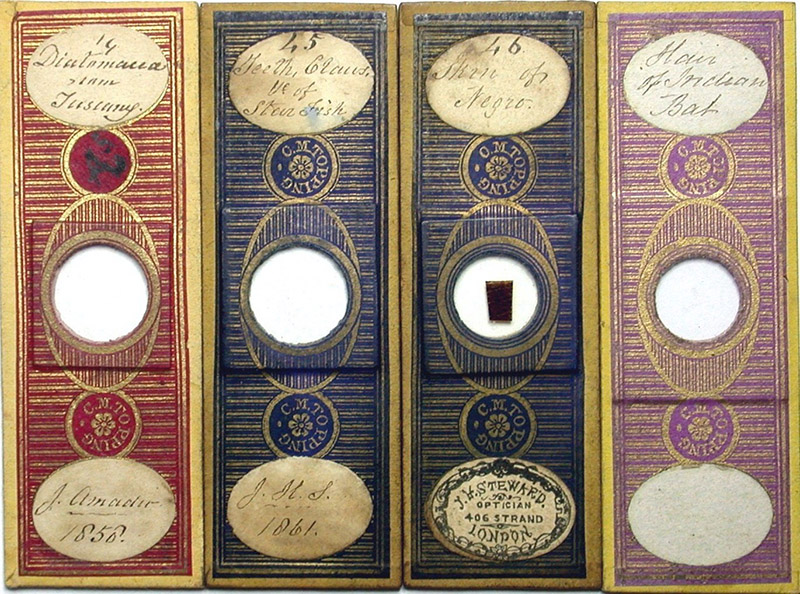

Rare color variants of Topping’s custom labels: blue and lavender.

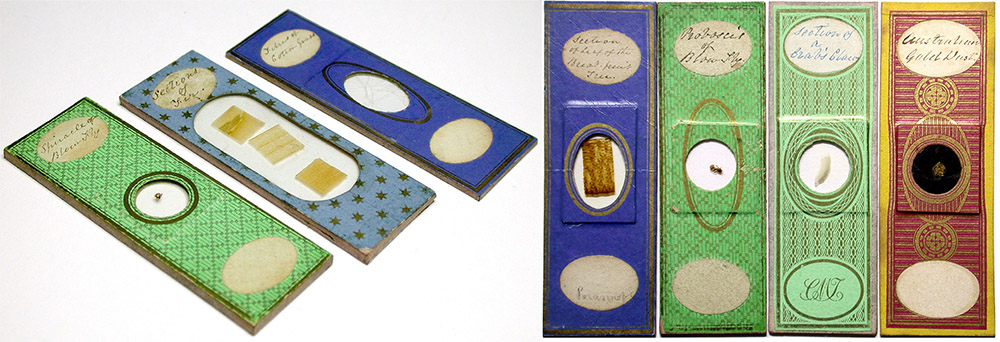

Figure 4.

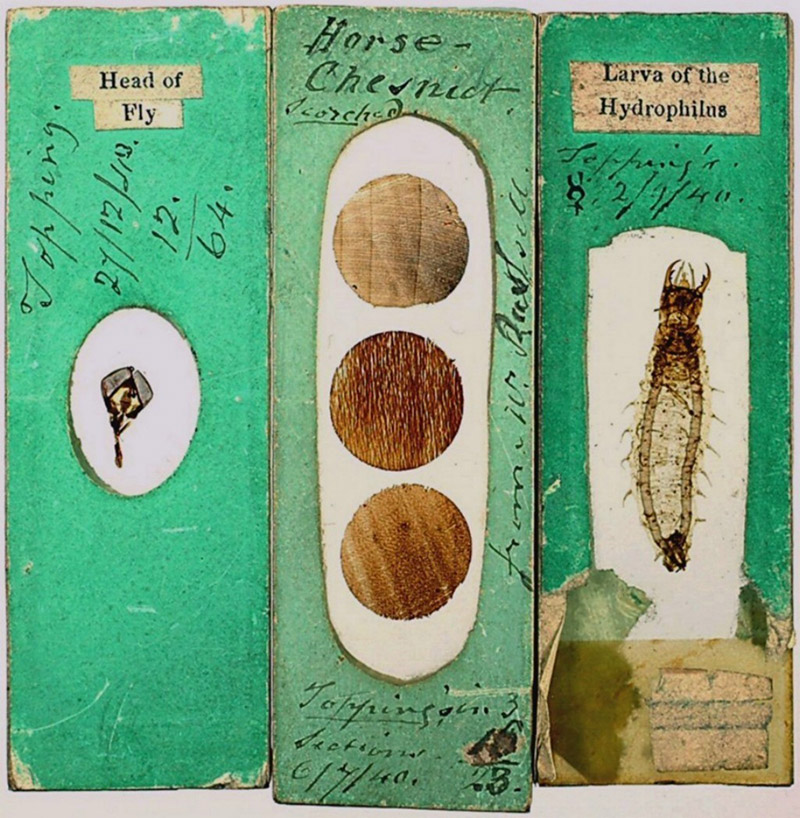

Three very early Topping mounts, all dated 1840.

Figure 5.

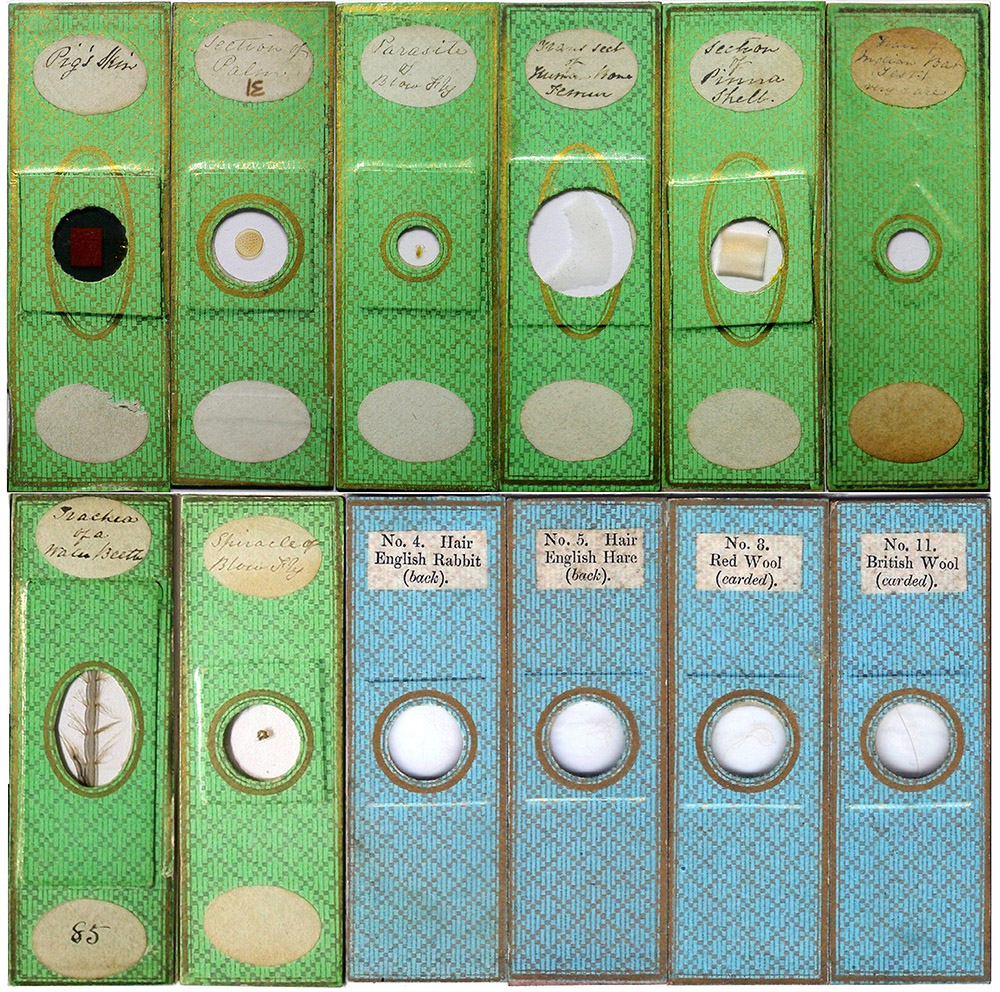

A selection of C.M. Topping slides that were produced during the early- to mid-1840s. The slides on the top row are all non-standard sizes. All of the gilt star-pattern slides have full cover papers front and back, with pink edge papers. Note that Topping used two different star-pattern papers: a common generic “sparkle stars”, and an unusual full 6-point star design. Many other slide-makers used the off-the-shelf “sparkle star” cover papers, in various colors.

Figure 6.

Topping used these gilt designs during the mid-1840s. The light green version was used for a variety of mounts. The light blue version appears to have been used exclusively for sets of a different animal hairs that were used to make felts. Of those, “The Microscopic Journal” noted in 1841 that “We have recently received from Mr. C.M. Topping … a set of twelve slides, containing the hairs of various animals, the fur or wool of which is used for felting. The objects are numbered according to their tendency to felt,

and, independent of their being generally interesting as objects of structural beauty, they are the more so to those particularly interested in the subject as a branch of manufacture. We recommend the set to all classes of observers”.

Figure 7.

Front and back views of a Topping mount with a rare paper pattern. It evidently was part of a set of felting fur preparations (see Figure 6).

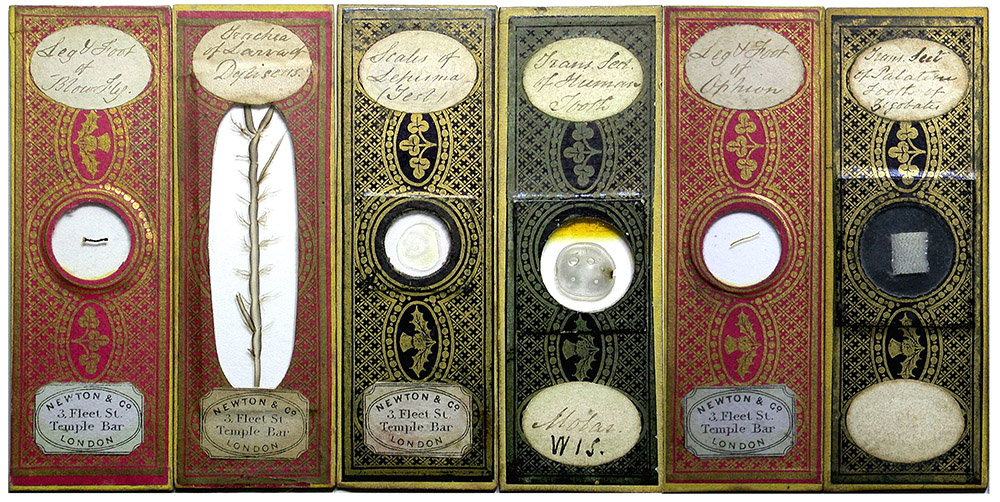

Figure 8.

C.M. Topping slides which use a gold on blue cover paper, probably from the mid-1840s. He used pink edge paper, as with all his other early- to mid-1840s slides. James Parkes and Son later retailed slides with similar cover papers, in blue, green, or red, but without edge papers.

Figure 9.

Topping slides that used a generic “Rose, Thistle, & Shamrock” design. Many other slide-makers used this off-the-shelf patterned paper. These likely date from the 1850s.

Figure 10.

Prior to the late 1840s, most of Topping’s preparations were made using a time-consuming process. A thin strip of pink paper was first glued along the four edges of the slide, then folded onto the front and back surfaces, extending approximately 1-2 mm. Oversize cover papers were next glued with adhesive to the front and back. Once set, the cover papers were trimmed exactly along the outside edges. With the introduction of Topping’s well known gilt pattern on light green paper covers (see Figure 2A) in the later

1840s, (also the first to carry his identifying monogram as part of the design), a different and less time-consuming procedure was used. The same thin pink edge papers were used to begin the process, but carried further on to the front glass surface. The front cover paper, now pre-cut to be 1-2 mm smaller in size than the finished slide, were simply centered and attached with adhesive. A plain green paper was applied to the back of the slide. Topping’s later red-papered productions also used this same method,

but with yellow edge papers, and a solid red paper on the back.

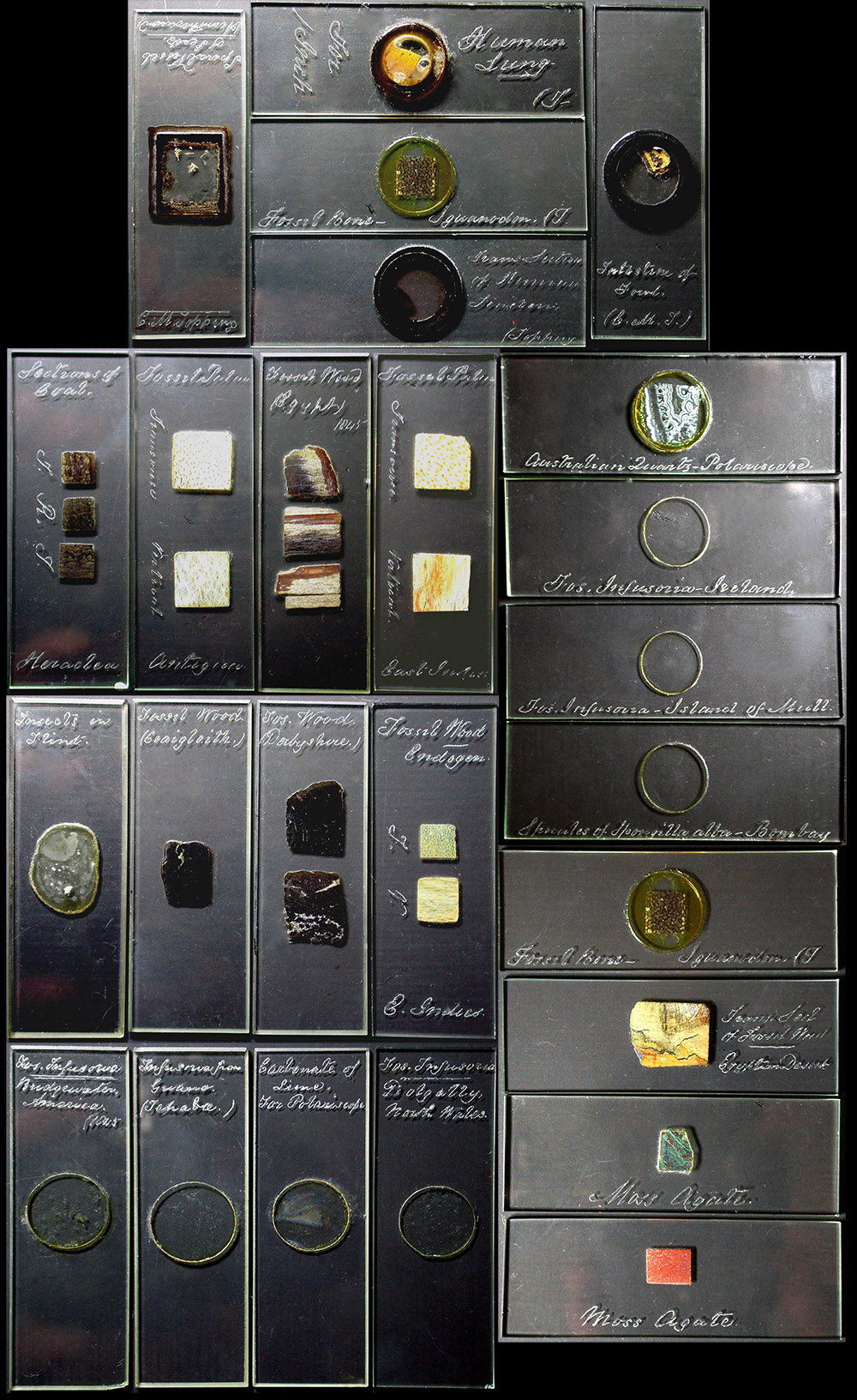

Figure 11.

Examples of C.M. Topping’s uncovered slides, with descriptions hand-etched into the glass with a diamond point. Some such slides bear his name or initials “C T”. The edges are finely polished.

Figure 12.

A selection of small Topping slides, all 5/8 to 3/4 inches wide by 2 to 2 1/4 inches long. These were likely sold in boxed sets. Details of construction and labeling suggest these were produced on commission from the 1840s on.

Figure 13.

Some Topping exhibition slides: three standard 1” x 3” slides and a 2” x 4” oversize slide.

Figure 14.

A selection of unusual Topping mounts. Sensational or exotic specimens that captured the public imagination were always good for sales. Topping’s long standing connections in the scientific community would have been helpful in securing one-of-a-kind objects from the museums and zoo. As an example, the slide on the far right (front and back) bears in Topping’s handwriting, “Human Hair, Beard” ~ “Turn over” and on rear “Beard of Thomas Beaufort second son of John of Gaunt, buried 1428, exhumed 1772”!

Figure 15.

A slide box with C.M. Topping’s label, and a handwritten list of a dozen preparations. The label gives his ca. 1861 - ca. 1867 address of 7 Haverstock Street, near City Road. Shown below are nine Topping slides that accompanied the box when recently purchased, and match the list.

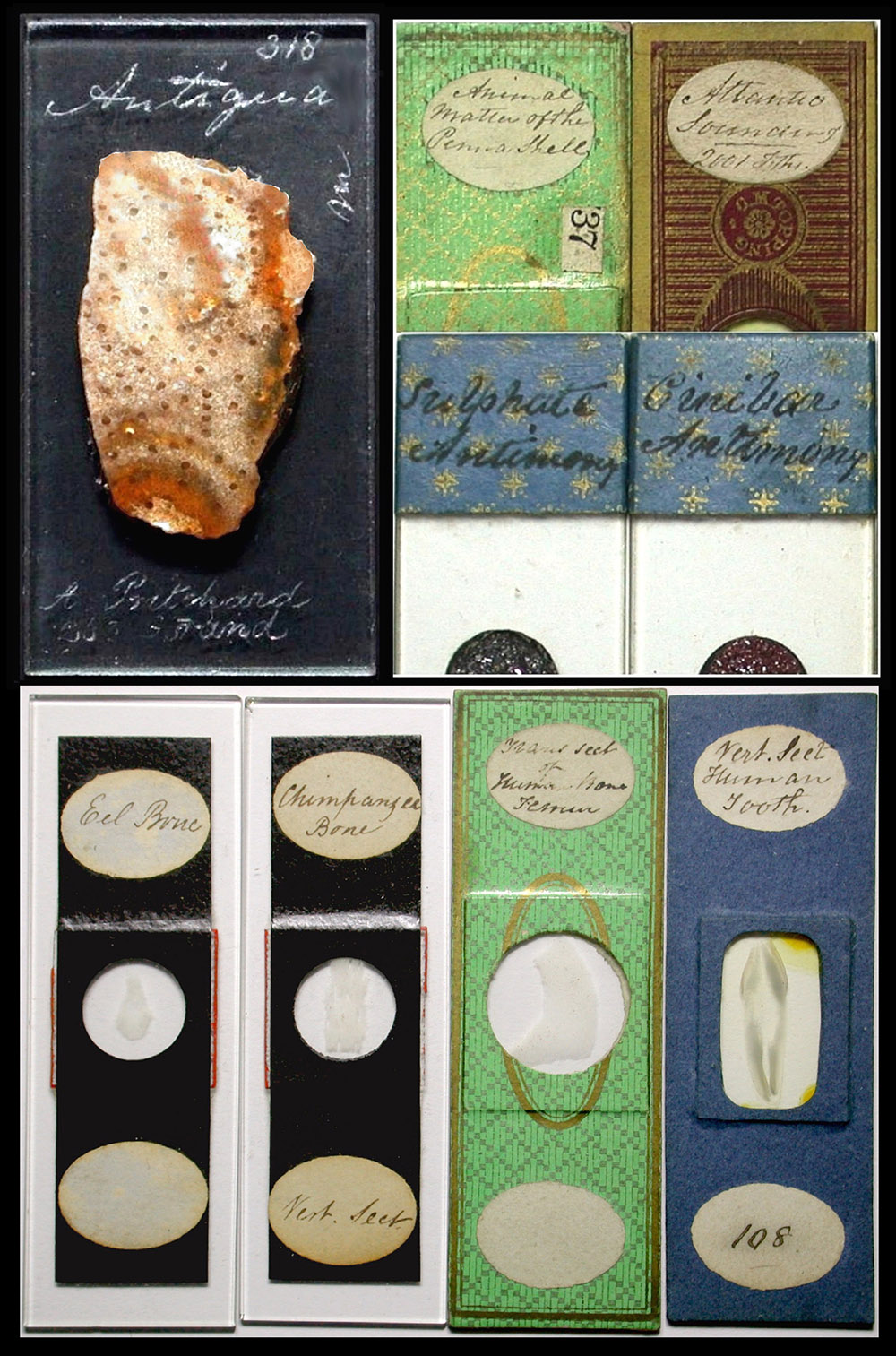

Figure 16.

(Top row) A comparison of Topping’s handwriting on his early- to mid-1840s slides, as compared to a late 1830s mineral preparation that has engraving that indicates retail by Andrew Pritchard at 263 Strand.

(Bottom row) Comparisons of two unsigned mounts constructed using red wax, sometimes attributed to Pritchard, with early Topping slides. Both are almost certainly by Topping. These suggest that Topping was making slides for Pritchard during the mid-1830s, possibly on into the 1840s. As we discuss in the text, Topping was employed as a printer during that time, and lived near the print shops of William Wilson and James Darkin, who produced Pritchard’s books. It is plausible that Topping took up the slide-making

profession as a result of meeting Pritchard through Wilson and/or Darkin.

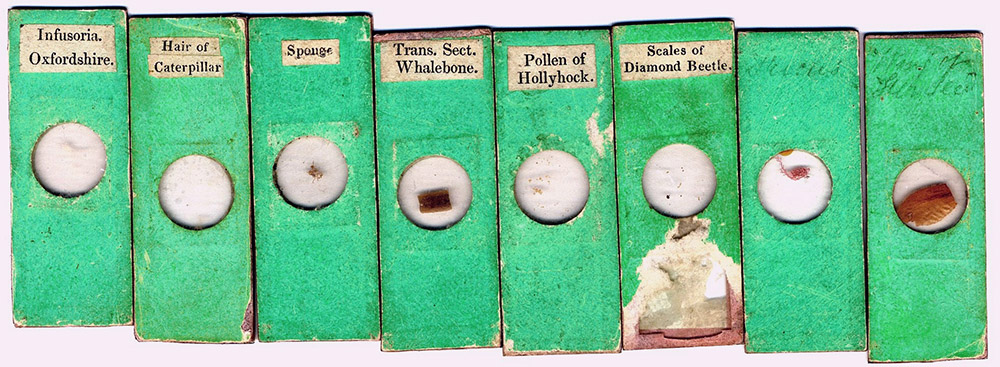

Figure 17.

Eight small slides, all of the same construction. The two on the right bear what appears to be Topping’s handwriting, and the other six carry printed labels like those found on slides that were retailed by Andrew Pritchard.

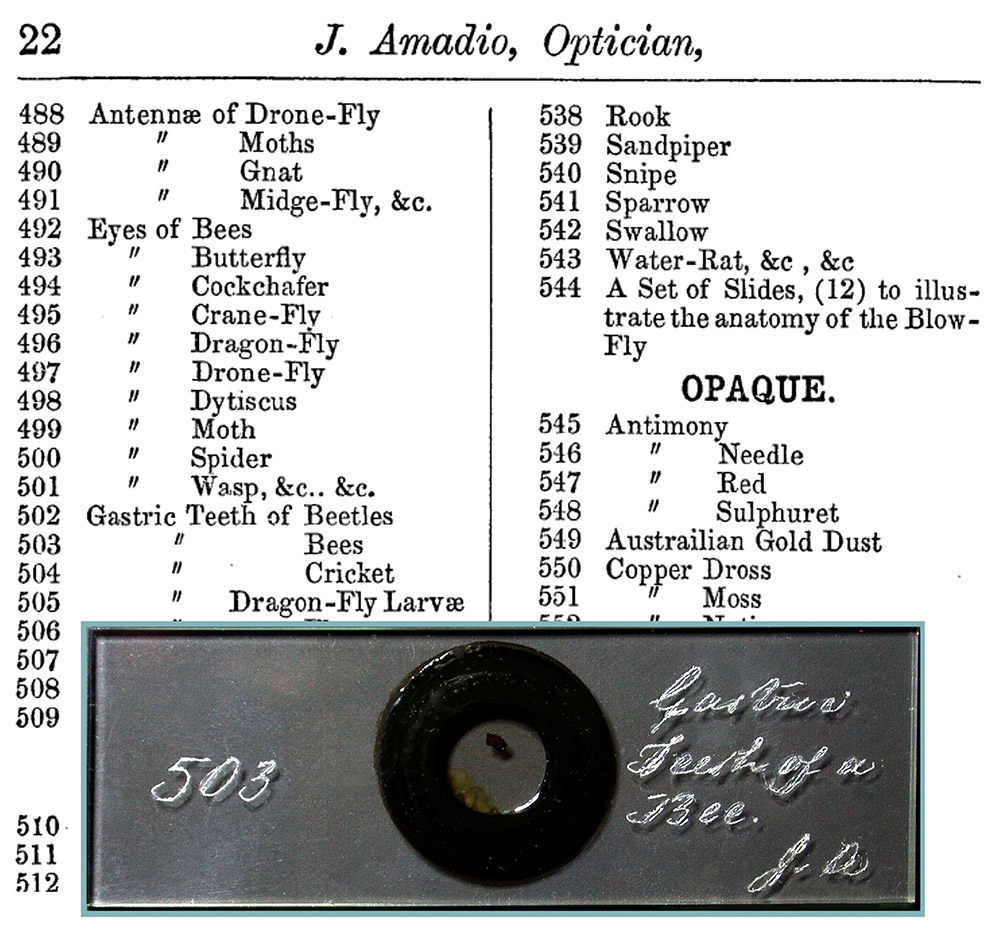

Figure 18.

A selection of Topping slides that were sold by microscope retailer Francis Amadio. The slide numbers correspond to extensive numbered lists of specimens advertised in Amadio’s catalogues for 1858 and 1864.

Figure 19.

An unusual engraved slide by Topping, corresponding to an item in Amadio’s 1858 catalogue. All of the other Amadio slides that we have seen are covered with Topping’s red custom papers.

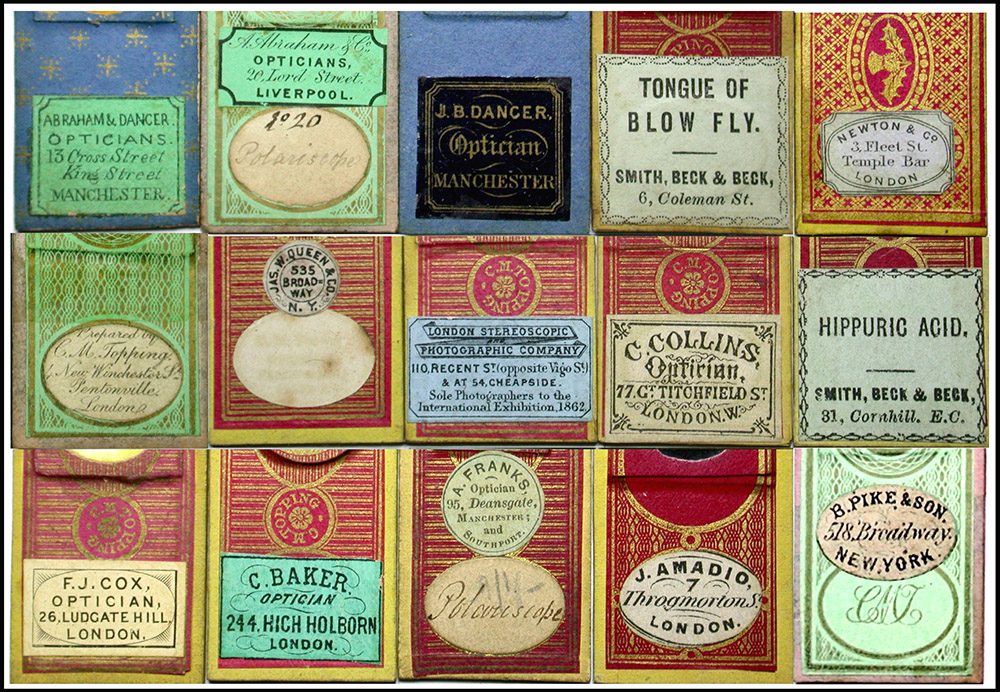

Figure 20.

Some of the many secondary reseller labels that can be found on Topping’s preparations. We have seen them from locations across the globe, including India, Australia, and the big Eastern cities in the US, as well as the many UK retail opticians. Preparations by Topping were always in demand, due to the variety of specimens and consistent high quality.

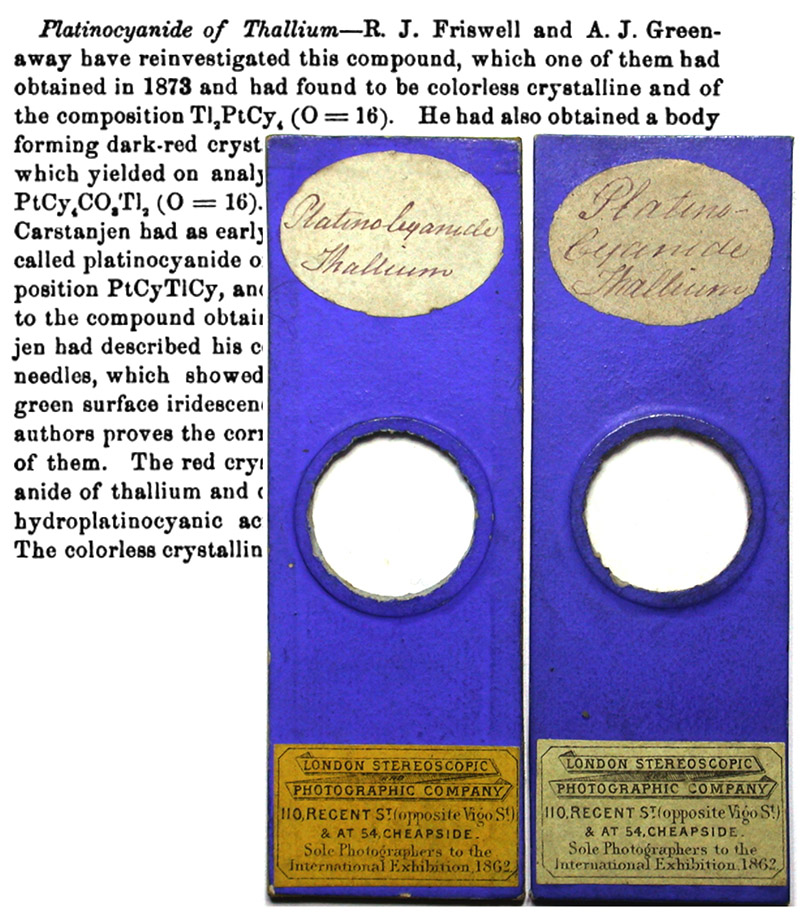

Figure 21.

Two preparations of Platinocyanide of Thallium, unsigned but attributable to C.M. Topping due to the handwriting. This chemical was first produced in 1871, so these were made very close to the end of Topping’s life. They were made using Topping’s original papering method, with bright blue covers and yellow edge papers, and were evidently custom-made for the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company.

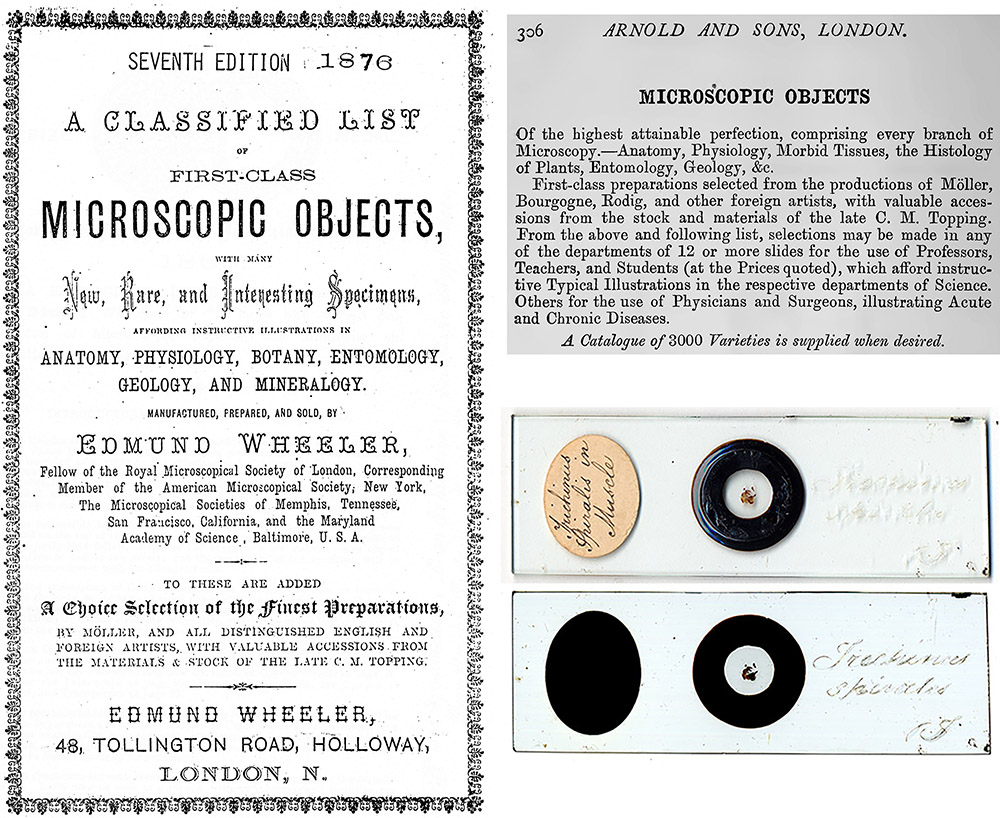

Figure 22.

Edmund Wheeler and Arnold & Sons both purchased substantial amounts of Charles Topping’s slides after his death. Occasionally, microscope slides are seen from those transactions, such as the illustrated slide that has the engraved handwriting and initials of C.M. Topping plus a glued-on label that is written in Wheeler’s hand.

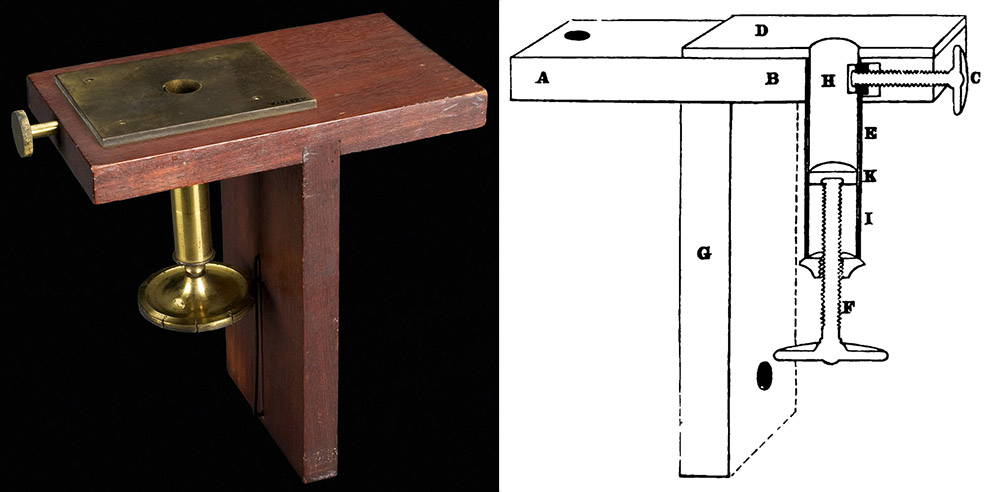

Figure 23.

A microtome of the type designed by C.M. Topping, circa 1840s. The microtome has a brass well to hold the specimen, a screw to raise the specimen, and a screw-clamp to hold the specimen in place for cutting. The user would slide a razor along the horizontal brass plate to slice off a thin section of specimen. Right image from Quekett, 1848. Left image adapted for nonprofit, educational purposes from http://collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects/co117910/topping-type-microtome-europe-1840-1850-microtome.

Charles Morgan Topping’s father, Amos Topping, was a master printer. He was the son of a silversmith (also named Amos), born during 1749 in Newcastle. He moved to London and learned the printing trade. By 1797, he was the printing overseer for The Times newspaper. Amos purchased membership in the Innkeeper’s Guild on January 19, 1802, which granted him substantial privileges (by that time, a guild’s name did not necessarily dictate the profession of its members). He took over the printing business at 3 Playhouse Yard, Blackfriars, London, at about the same time. He was sufficiently established by June 7, 1803 to take on an apprentice. The title page from a book printed by Amos Topping is shown in Figure 24.

He married Elizabeth Dellesalle on September 24, 1786, at the parish church of St. Andrew Holborn, London. They had two daughters, born in 1788 and 1790. The first son, Charles Morgan Topping, was born on May 21, 1799 (Figure 25). Three daughters and another son followed.

Amos was known to some extent among the citizenry of London. His 1817 death was announced in The Gentleman’s Magazine: “Sept. 7. Mr. Amos Topping, printer, of Playhouse-yard, Blackfriars”.

Charles inherited his father’s business (Figure 26). He was recorded as owning the print works at Playhouse Yard as late as 1825.

Charles M. Topping married Sarah Preston on March 15, 1824. They followed the tradition in re-using family names for their children. Their first child, Charles Amos Topping, was born in 1827. A daughter, Sarah was born in 1828. The third child, Amos, who was christened on March 6, 1831, followed in his father’s tracks and also became a celebrated maker of microscope slides. Another daughter, Harrietta followed in 1837, then another son, Henry, in 1838.

All of the Topping children were born at different locations: Frog Lane, Islington (1827), Queen’s Street, Islington (1828), Colebrooke Row, Islington (1831), Park Lane, Islington (1837), and Bride Lane, Islington (1838). That extensive moving around is not consistent with a person who owns a printing company. Additionally, Topping was not recorded as being a printer in directories or other records after 1825, and the Playhouse Yard print shop was owned by Lowe and Harvey by 1828. Yet, the 1841 census and many later records described Topping’s occupation as “printer”. This suggests that he worked for another printer(s), after selling his business to Lowe and Harvey circa 1825.

For whom Topping worked is not known, but a reasonable guess can be made. Most of the streets on which the Toppings lived do not appear to exist now, but two that do may be significant. Colebrooke Row is a roughly 14 minute walk from 57 Skinner Street, the site of the printing business of William Wilson, and Bride Street is about a 10 minute walk from 3 Cloudesley Street, the site of the printing business of James Darkin. Those two printers produced the microscope books of Andrew Pritchard. Although firm evidence is lacking, these circumstances suggest that, if Topping worked for Wilson and/or Darkin, he would have met one of the pre-eminent microscope makers of the era. That might have piqued Topping’s interest in preparing specimens for microscopical investigation (Figures 16 and 17).

We can confidently state that Topping began to commercially prepare microscope slides while still working as a printer. A note in the January, 1841, issue of The Microscopic Journal stated, “Microscopic Objects - We have much pleasure in recommending to the notice of Microscopists Mr. C.M. Topping, of No. 26, Bride Street, Liverpool road, Islington, who has devoted himself with much zeal, for the last three or four years, to this increasing business. His terms are moderate, and the objects very carefully prepared”. This indicates that Topping began seriously working at preparing slides around 1837-38.

Questions have been raised about how Charles Topping learned to prepare microscope specimens. Among Topping’s earliest slides are thinly-sectioned minerals and fossils (Figures 11 and 16). Falcon-Lang and Digrius speculated that he might have learned the necessary techniques during an apprenticeship with William Darker (ca. 1811-1864). That is highly unlikely. Darker did not own a shop until the mid-1830s, and began producing microscope slides some time after that. Moreover, Topping was about 10 years older than Darker, and Topping’s known history would not allow for a substantial period of time with Darker in Lambeth. Instead, Topping probably learned lapidary slide preparation the way Darker and others did, by trial and error. He could have learned the basics from Henry Witham’s 1831 book, Observations on Fossil Vegetables Accompanied by Representations of Their Internal Structure as Seen Through the Microscope. It included detailed directions for producing slides of thinly-sectioned fossils, stating that, “A lapidary, by attending to the above directions, will find no difficulty in reducing any piece of petrified wood to that degree of thinness sufficient to render its structure visible; and any one, even without the aid of the mechanism employed by the lapidary, may accomplish that object by attending to the following directions”.

Topping’s early output included additional types of slides. The Microscopic Journal wrote in 1841, “Topping's Objects illustrative of the Process of Felting - We have recently received from Mr. C.M. Topping … a set of twelve slides, containing the hairs of various animals, the fur or wool of which is used for felting. The objects are numbered according to their tendency to felt, and, independent of their being generally interesting as objects of structural beauty, they are the more so to those particularly interested in the subject as a branch of manufacture. We recommend the set to all classes of observers. We observe that Mr. Topping uses strips of mahogany veneer, (instead of slips of glass) with a hole bored through the centre for the glass to fix the object upon. This is a decided improvement over the old plan” (Figures 6 and 7).

Within a few years, Topping had established a strong reputation. George F. Richardson’s 1842 Geology for Beginners listed, “objects for microscopic investigation, both recent and fossil, are prepared by Mr. Topping, 26, Bride Street, Liverpool Road, Islington”. Richardson also gave Topping as a source for gummed paper, probably made by Topping at the print shop. For making one’s own slides, The London Physiological Journal recommended in 1842, “plate glass of different sizes and thickness, drilled in this way, can be obtained of … Mr. Topping”. In addition, Topping aided surgeon W.B. Kesteven with micro-dissection of bone structures in 1842, and discovered mange mites by “examining microscopically the contents of the pustules in a mangy dog” in 1843.

During 1843, the Toppings moved a short distance, from 26 Bride Street, Islington to 1 York Place, Pentonville (Figure 28).

Gideon Mantell’s 1844 Medals of Creation recommended, “Topping, Mr.,1, York-place, Pentonville-hill; supplies boards and cases, and every kind of fossil infusoria, &c.; polished slices of fossil wood and teeth; and all kinds of microscopical objects, admirably prepared, and at moderate prices”. Alfred Smee wrote in 1846, “strips of thick, and pieces of thin glass, I always procured of Mr. Topping, No. 1, Penton-place, Pentonville-hill, who is moderate in his charges and exceedingly obliging”.

The 1846 Post Office Directory of London listed Topping as a “preparer of microscope objects”.

In February, 1846, Charles Topping became an Associate Member of the Microscopical Society of London. The Society later wrote that this was “in recognition of his services to microscopical pursuits”. Why he did not become a Fellow is not known. It may reflect social standing, although tradesmen such as William Darker were Fellows. Another possibility is that dues were lower for Associates, and Topping was satisfied with that level of access to the wealthy and well-connected microscopists of London.

John Quekett, also a member of the Microscopical Society of London, quoted Topping extensively in the first edition of his Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope (1848). This included descriptions of Topping’s methods on mounting specimens and applying cover papers to slides, an illustrated description of Topping’s microtome (see Figure 23, above), an extensive list of items suitable for microscopical examination that was provided by Topping, and descriptions of mounted and unmounted objects available for sale by Topping. John Quekett’s daily journals from the 1840s include numerous entries of Topping visiting him, trading specimens, and discussing various aspects of microscopy. The entries give the impression of friendly and mutually-respectful relationship between the two men. It is no surprise that Topping would have been one of Quekett’s favored resources. Little was written about any other slide-maker in Quekett’s first edition. One can imagine that this popular book was very helpful for Topping’s business. Successive editions of Quekett’s book also quoted heavily from Topping.

Topping moved his home and shop a short distance during 1848, to 4 New Winchester Street. Topping described this shop as being “opposite my late residence” (Figure 28).

The 1851 census listed Topping as a “preparer of anatomical and microscopical objects”. The 1851 Post Office Directory listed Topping as “preparer of microscopic objects, & dealer in second-hand microscopes”. Despite his successes as a microscopist, Topping retained his old occupation, as evidenced by being described as a “printer” on daughter Sarah’s May 18, 1851 marriage record.

He entered 1851’s Great Exhibition with “Microscopic objects. Test objects and fossil earths. Fossil and recent vegetable structures. Dissections of insects. Bone, teeth, shell, &c. Injected preparations”. The resulting medal was prominently declared in future advertisements (Figure 29).

“Five cases of microscopic objects” were displayed by Topping at the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

As with Quekett’s books, Jabez Hogg’s The Microscope made extensive references to Topping. Some examples, from the 1856 edition: “Mr. Topping, of New Winchester Street, Pentonville, has furnished me with the following list of 100 interesting and popular objects prepared by him”; “Mr. Topping, the careful preparer of microscopic objects, generally furnishes three kinds of test-objects, which he covers with the thinnest glass, in order that object-glasses of the highest powers may be used in the examination of them. The following are arranged according to their difficulty as test-objects”; “Another process, which may be termed the chemical process, was published in the Comptes Rendus, 1841, as the invention of M. Doyers. According to this, an aqueous solution of bichromate of potass, 1048 grains to two pints of water, is propelled into the vessels; and after a short time, in the same manner and in the same vessels, an aqueous solution of acetate of lead, 2000 grains to a pint of water, is injected. This is an excellent method, as the material is quite fluid, and the precipitation of the chromate of lead which takes place in the vessels themselves gives a fine sulphur-yellow colour. Mr. Topping prepares many fine injections in this way”; “The fluid which Mr. Topping uses for mounting consists of one ounce of rectified spirit to five ounces of distilled water; this he thinks superior to any other combination. To preserve delicate colours, however, he prefers to use a solution of acetate of alumina, one ounce of the acetate to four ounces of distilled water: of other solutions he says, that they tend to destroy the colouring matter of delicate objects, and ultimately spoil them by rendering them opaque”; and included an engraving of a housefly proboscis that was made from a preparation by C.M. Topping (Figure 30).

The 1861 census described Topping as a “microscopic anatomist”, and further noted that he employed 3 men. Two of these were undoubtedly his younger sons, Amos and Henry, who lived nearby and were each described as being “opticians” on that census. The eldest son, Charles Amos Topping, lived in Ipswitch, Suffolk, working as a “printer machine manager”. The third worker is unknown, but was presumably an unrelated slide-maker. All of Topping’s sons and daughters probably worked for him at some time, as children of a tradesman would be expected to do. Youngest son Henry died in 1868, when only 29 years old. Amos went on to become a famous slide-maker in his own right.

Between the time of the April 7, 1861, census, and the following May, Topping moved a short distance to 7 Haverstock Street (Figure 15). Guides to the 1862 London International Exhibition, which began in May, 1862, listed Topping at that address.

Topping joined the Quekett Microscopical Club on October 26, 1866.

Charles Morgan Topping’s wife, Sarah, died during the early- to mid-1860s. We have not been able to locate her death record.

Lionel Smith Beale’s 1867 The Microscope in Its Application to Practical Medicine, third edition, recommended Topping as a supplier of microscope preparations, living at “11 Loader’s-terrace, Manor-road, Bermondsey”. This is across the Thames and a substantial distance from his previous addresses.

This move probably coincided with Sarah’s death, and Charles going to live with his other wife and family. The details of Topping’s second life were sorted by Steve Gill, and his masterful detective work was published in 2011 in the Quekett Microscopical Journal. The 1871 census listed Topping at 41 Evelyn Street, Deptford, living with his wife, Emma, and 6 children. All of them were Charles’ children. The eldest, Martha, then 17 years old, later listed on her marriage record her father’s name: “Charles Morgan Topping, microscopist”. Topping was also listed as the father on the christening records of son Charles (13 in 1871) and daughter Emma (8 in 1871). Young Charles even gave the name Charles Morgan Topping to one of his sons. Wife Emma’s 1905 death record stated that she was the “widow of Charles Morgan Topping, microscopist”.

The 1871 list of members of the Royal Microscopical Society, which would have been prepared in late 1870 or early 1871, gave the same address in Deptford.

Charles Morgan Topping died on September 6, 1874 from “uremia”. He was then 75 years old.

The circumstances of C.M. Topping’s burial suggest that he was estranged from Amos and other members of his first family. He was buried in a common grave (i.e., a “pauper’s grave”) in Kent.

The Royal Microscopical Society published a memoriam of Topping in early 1875. Curiously, it has the wrong dates for both his birth and death; we have obtained official records with the dates of C.M. Topping’s birth (May 21, 1799) and death (September 6, 1874). “Charles Morgan Topping was born May 23, 1800 (sic), in the parish of St. Bride's, Fleet Street, London. In 1840 he adopted the profession of preparing and mounting objects for the microscope, in which he acquired great skill, so that his slides were very generally sought for, and occupy an important place in most collections. Mr. Topping was remarkably successful in preparing minute injections; some of his preparations injected with chromate of lead are amongst the finest that have been produced. In recognition of his services to microscopical pursuits, he was elected an Associate of this Society on February 10, 1846. He died on September 5, 1874 (sic)”. This obituary may explain why Brian Bracegirdle’s Microscopical Mounts and Mounters gives the incorrect year for Topping’s birth.

Slide-maker and retailer Edmund Wheeler purchased a substantial quantity of Topping’s remaining slides, and advertised them for sale (Figure 22). Another London dealer, Arnold and Sons, acquired another portion of Topping’s stock for resale (Figure 22).

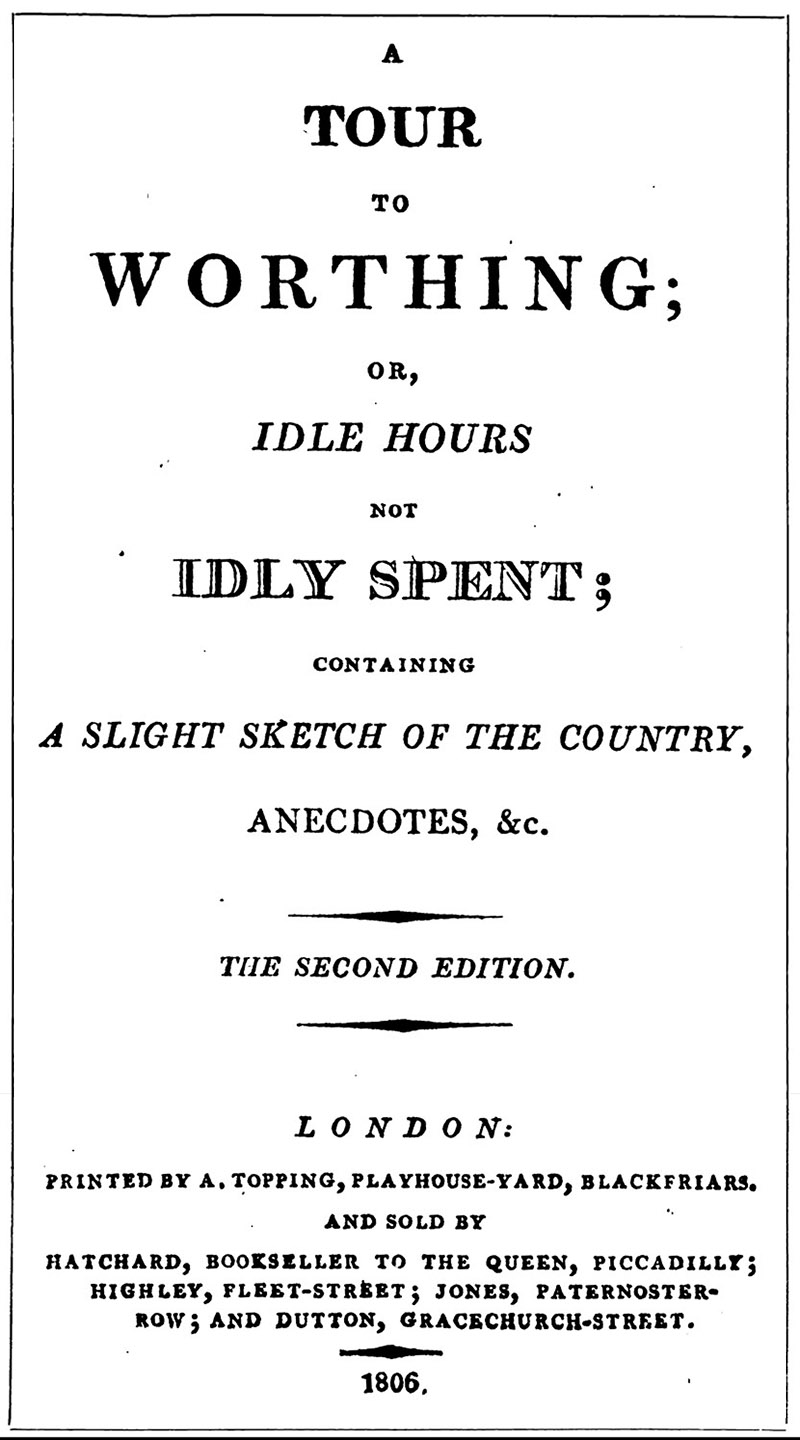

Figure 24.

Title page of a book that was printed in by C.M. Topping’s father, Amos.

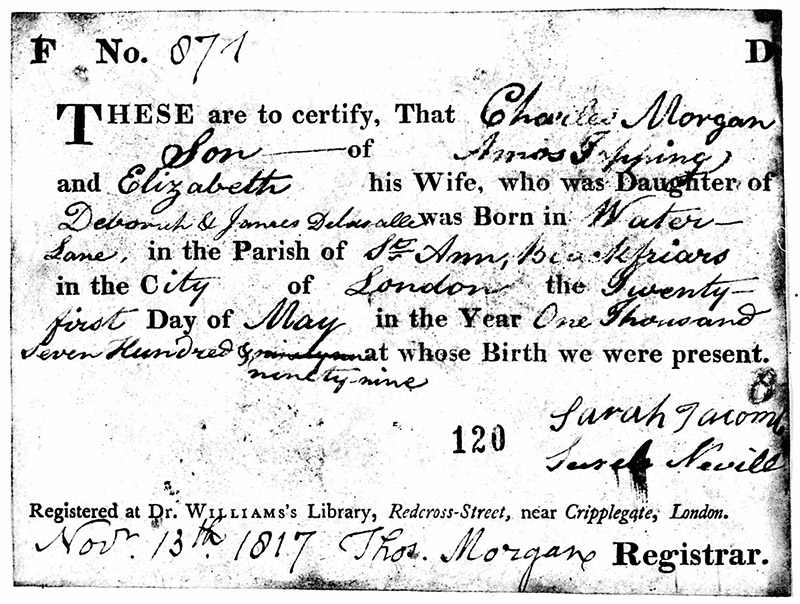

Figure 25.

May 21, 1799 record of the birth of Charles Morgan Topping.

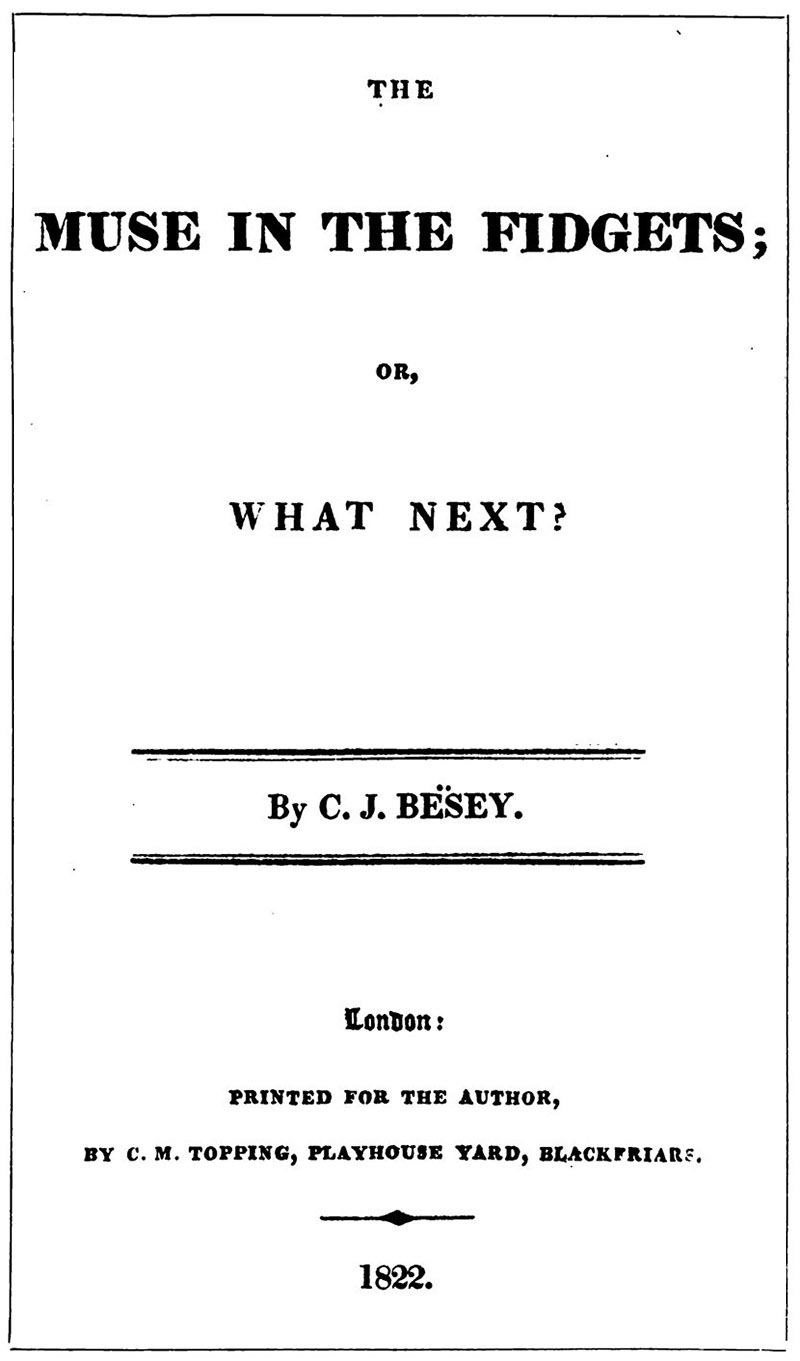

Figure 26.

Title page of a book printed by Charles M. Topping in 1822. He owned this printing shop until at least 1825, but had sold it by 1828.

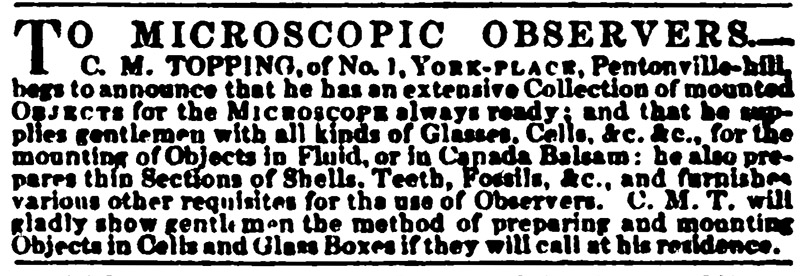

Figure 27.

An 1843 advertisement.

Figure 28.

Advertisements from 1848.

(A) from John Ralfs’ “The British Desmidieae”.

(B) from John Quekett’s “Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope” (first edition).

Figure 29.

Advertisement from Adolphe Hannover’s 1853 “On the Construction and Use of the Microscope”.

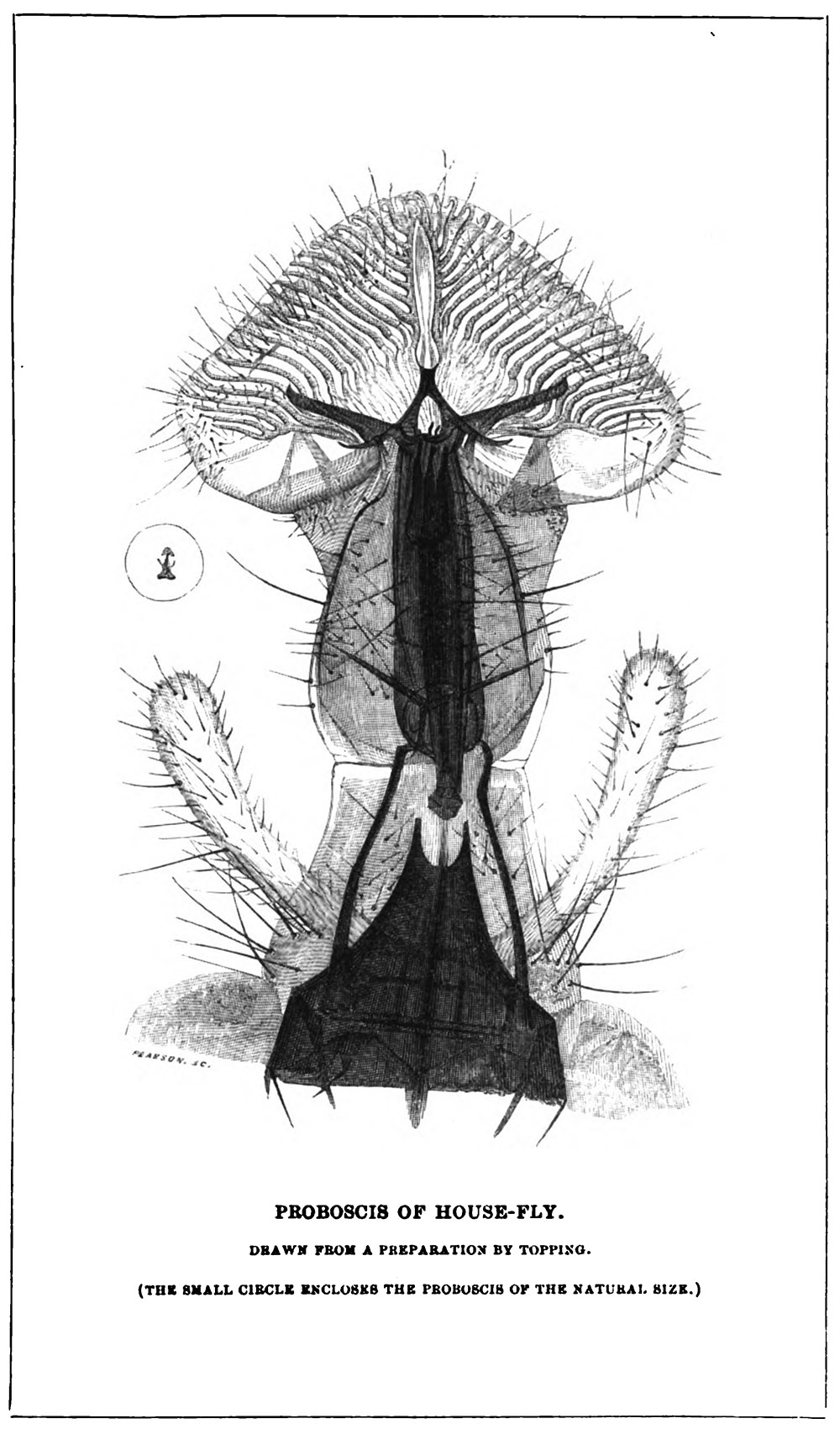

Figure 30.

Proboscis of a housefly, “drawn from a preparation by Topping”. From Jabez Hogg’s 1856 “The Microscope”, second edition. This is the only plate in the book that noted the source of the specimen.

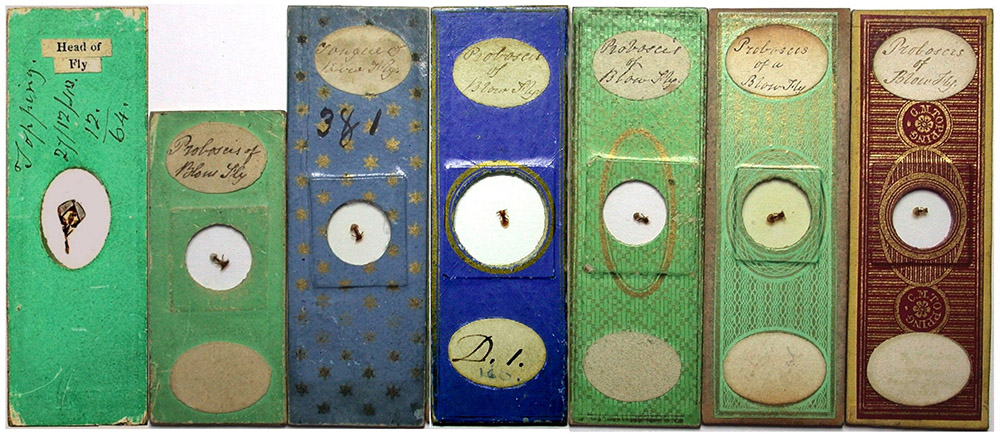

Figure 31.

Several decades of C.M. Topping preparations of “Proboscis of Blow Fly”. He was well known for his skill in preparing this delicate object.

Acknowledgement

Our thanks to Trevor Gillingwater for generously providing a copy of the photograph of Charles Topping.

All comments to the authors Brian Stevenson and Howard Lynk are welcomed.

Resources

Amadio, Joseph (1858) A Catalogue of Achromatic Microscopes and other Optical, Philosophical, and Mathematical Instruments, Manufactured and Sold by J. Amadio, Optician to the Admiralty, 7, Throgmorton Street, London

Amadio, Francis and Joseph Amadio (1864) A Catalogue of Achromatic Microscopes and other Optical, Philosophical, and Mathematical Instruments, Manufactured and Sold by F. & J. Amadio, Opticians to the Admiralty, 7, Throgmorton Street, London

Arnold and Sons (1880) Catalogue of Surgical Instruments, page 306

The Athenaeum (1843) Advertisement from C.M. Topping, Vol. 2, November 25, page 1033

Beale, Lionel S. (1868) How to Work With the Microscope, fourth edition, Harrison, London, page 363

Besey, C.J. (1822) The Muse in the Fidgets, printed by C.M. Topping

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London, pages 94-95, 168, 176, 202, 204, 222, and 224, and Plates 32-O, 36-A to N, 49-G, 50-E, 59-B, 59-D, 60-B, and 60-C

Christening record of Charles Morgan Topping (1799) Parish records of St. Ann, Blackfriars, accessed through ancestry.com

Christening record of Charles Amos Topping (1827) Parish records of St. Mary, Islington, father’s occupation: “printer”, residence at Frog Lane, accessed through ancestry.com

Christening record of Sarah Topping (1829) Parish records of St. Mary, Islington, father’s occupation: “printer”, residence at Queens Street, accessed through ancestry.com

Christening record of Amos Topping (1831) Parish records of St. Mary, Islington, father’s occupation: “printer”, residence at Colebrooke Row, accessed through ancestry.com

Christening record of Harrietta Topping (1837) Parish records of St. Mary, Islington, father’s occupation: “compositor”, residence at Park Lane, accessed through ancestry.com

Christening record of Henry Topping (1838) Parish records of St. Mary, Islington, father’s occupation: “printer”, residence at Bride Lane, accessed through ancestry.com

Cowie's Printer's Pocket-Book and Manual (1835) C.M. Topping is not listed among the master printers of London

Davidson, Brian (2007) Topping slides 1840-50, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 40, pages 375-388

Davidson, Brian, and Howard Lynk (2010) The papered slides of C.M. Topping, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 41, pages 311-321

Death record of Charles Morgan Topping (1874)

England census and other records, accessed through ancestry.com

Exposition Universelle, 1855, Catalogue des Objets Exposés Dans la Section (1855) “415 Topping, C.M., 4 New Winchester-street, London. Five cases of microscopic objects”, page 24

Freedom of the City papers for Amos Topping (1902) accessed through ancestry.com

“G.” (1806) A Tour of Worthing, printed by A. Topping

The Gentleman’s Magazine (1817) Obituaries: “Sept. 7. Mr. Amos Topping, printer, of Playhouse-yard, Blackfriars”, Vol. 87, page 378

Gill, Steve (2011) The two families of Charles Morgan Topping, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 41, pages 553-555

Handover, P.M. (1956) The Site of the Office of the Times, Times Publishing, London, page 63

Hannover, Adolphe (1853) On the Construction and Use of the Microscope, Sutherland and Knox, Edinburgh, advertisement from C.M. Topping at back of the book

Hogg, Jabez (1856) The Microscope, second edition, H. Ingram & Co., London, pages 87, 95, 99-100, and 307, and plate VII

Hogg, Jabez (1858) The Microscope, third edition, G. Routledge & Co., London, page 138

Holden’s Triennial Directory for 1805, 1806, 1807 (1805) “Topping Amos, printer, Play-house yard, Blackfriars”

Kesteven, W.B. (1842) Letter, The Medical Times and Gazette, page 224

London and County Directory (1811) “Topping A. printer, 3, Playhouse yard, Blackfriars”

London Physiological Journal (1843) Hints to microscopists, Vol. 1, pages 88-90

London Physiological Journal (1843) Microscopical Society of London, Vol. 1, page 124

Lynk, Howard (2108) The slides of C.M. Topping - another look, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 43, pages 181-193

Lynk, Howard, and Robert H. Nuttall (2005) A note on some newly-identified Topping slides, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 40, pages 61-63

Mantell, Gideon A. (1843) The Medals of Creation, H.G. Bohn, London, page 988

Marriage record of Amos Topping and Elizabeth Dellesalle (1786) Parish records of St. Andrew, Holborn, accessed through ancestry.com

Marriage record of Charles Morgan Topping and Sarah Preston (1824) Parish records of St. George the Martyr, Southwark, accessed through ancestry.com

Marriage record of Charles Amos Topping and Jane Williams (1849) Occupation of his father, Charles Morgan Topping: “printer”, Parish records of St James, Clerkenwell, accessed through ancestry.com

Marriage record of Sarah Ann Topping and John George Swann (1851) Occupation of his father, Charles Morgan Topping: “printer”, Parish records of St James, Clerkenwell, accessed through ancestry.com

The Medical Times (1846) “Microscopical Society, March 18 … Mr. C.M. Topping was admitted an associate, and Mr. Z.D. Hunt a member”, Vol. 14, page 64

The Microscopic Journal (1841) Microscopic objects, page 16

The Microscopic Journal (1841) Topping's objects illustrative of the process of felting, page 160

The Microscopical Society of London, Report of the Seventh Anniversary (1847) “Topping, C.M., Esq., (Associate), 1, York-place, New-road, Pentonville”, page 31

Mitchell, John (1823) An Ode to France, printed by C.M. Topping

The Monthly Microscopical Journal (1871) “Members … Topping, Charles Morgan. 41 Evelyn-street, Deptford, S.E.”, Vol. 6, page 21

The Monthly Microscopical Journal (1875) Obituary for Charles Mogan Topping, Vol. 13, page 107

Morrison, Stanley (1950) The History of the Times: “The Thunderer” in the Making, 1785-1841, page 39

Nuttall, Robert H. (2002) Artefacts as evidence: an early collection of slides prepared by C.M. Topping, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 39, pages 409-426

Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851) “667 Topping, C.M. 4 New Winchester St. Pentonville Hill - Microscopic objects. Test objects and fossil earths. Fossil and recent vegetable structures. Dissections of insects. Bone, teeth, shell, &c. Injected preparations”, page 70

Pigot’s Directory (1825) “Topping Cs., 3 Playhouse-yard, Blkfrs”, page 203

The Printers’ Assistant (1810) Master Printers: “Topping, Playhouse yard, Blackfriars”, page 31

The Printers’ Manual (1829) Printers: “Lowe and Harvey, 3, Playhouse-yard”, page 44

Pritchard, Andrew (1834) The Natural History of Animalcules, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by W. Wilson, 57 Skinner Street

Pritchard, Andrew (1838) Microscopic Illustrations of Living Objects, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by Wilson and Son, 57 Skinner Street

Pritchard, Andrew (1840) Microscopic Illustrations of Living Objects, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by Wilson and Son, 57 Skinner Street

Pritchard, Andrew (1842) A History of Infusoria, Living and Fossil, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by J. Darkin, 3 Cloudesley Street, Islington

Pritchard, Andrew (1843) A General History of Animalcules, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by J. Darkin, 3 Cloudesley Street, Islington

Pritchard, Andrew (1844) Notes on Natural History, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by J. Darkin, 3 Cloudesley Street, Islington

Pritchard, Andrew (1847) Microscopic Objects, Whittaker and Co., London, printed by J. Darkin, 3 Cloudesley Street, Islington

Post Office Directory, London (1846) “Topping, Charles M., preparer of microscope objects, 1 York place, Pentonville hill”, page 516

Post Office Directory, London (1851) “Topping Chas. Morgan, preparer of microscopic objects, & dealer in second-hand microscopes, 4 New Winchester street, Pentonville”, page 1027

Post Office Directory, London (1856) “Topping Charles Morgan, preparer of microscopic objects, 4 New Winchester street, Winchester street, Pentonville” and “Bird and Beast Stuffers … Topping Chas. M. (microscopic), 4 New Winchester street, Pentonville”, pages 1425 and 1546

Quekett, John Thomas (1848) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures, 1st Edition, H. Bailliere, London, pages 257, 285, 308-309, 351, 366, 369, 376, 377, 408, 410, 431, 437, 450, 464, and advertisement from C.M. Topping at the back of the book

Quekett, John Thomas (1852) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures, 2nd Edition, H. Bailliere, London

Quekett, John Thomas (1855) A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope: Including the Different Methods of Preparing and Examining Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Structures, 3rd Edition, H. Bailliere, London

Quekett Microscopical Club, Fourth Report and List of Members (1869) “Oct. 26, 1866, Topping, C.M., A.R.M.S, 11 Loaders-terrace, Manor-road, Bermondsey, S.E.”, page 31

Ralfs, John (1848) The British Desmidieae, Reeve, Benham, and Reeve, London, advertisement from C.M. Topping at back of the book

Richardson, George F. (1842) Geology for Beginners, pages 86 and 88

Smee, Alfred (1846) The Potatoe Plant, Its Uses and Properties, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, London, page 14

Stevenson, Brian, and Howard Lynk (2016) William Hill Darker, the scientist’s engineer, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 42, pages 559-575

Stevenson, Brian, and Stanley Warren (2015) Edmund Wheeler: a man of parts, Quekett Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 42, pages 339-354

Wheeler, Edmund (1876) A Classified List of First-Class Microscopic Objects, etc., 7th edition

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the February 2019 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .