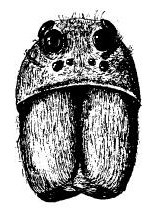

| A front view of a typical wolf spider, showing the arrangement of the eight eyes and impressive fangs. |

|

BRIGHT-EYED SINGERS by William H. Amos, Vermont, US |

"There's a wolf spider over there on the tree," I told an unbelieving grandson. He had reason to doubt, for it was a dark night, the tree was fifty feet away, and Grandpa was known for pulling legs. My flashlight picked up tiny greenish points of light, different from others that clearly were dew. We followed the beam of light and before we reached the tree, the bright pinpricks suddenly moved and disappeared. "Wow!" The boy was clearly impressed. Once at the tree, close searching revealed the spider wedged in a crack.

A few months ago in a Trinidad rain forest, also long after dark, my flashlight picked out a tarantula poised on a broad leaf. "Wow!" said my friends, impressed more by the great spider's size than by my trick of finding it.

I've used this method most of my life, from demonstrations in a darkened laboratory to expeditions far away. The most remarkable instance occurred in Hawai'i's wide mountainous Ka'u Desert close to midnight, when my friend Maile and I went bouncing into that forbidding arid land searching for wolf spiders, or lycosids. Her jeep's headlights picked up thousands of gleaming jewels scattered across the cinders and rocky plain. As we drew near, they darted away from the car, or with a half turn simply winked off. "Wow!" she said, which seems to be the appropriate response to shining spider eyes.

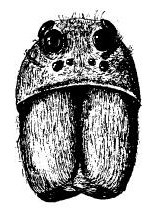

Vision in wolf spiders is vital for stalking and capturing prey, and for identifying the opposite sex during courtship, when scent, or production of pheromones, confirms sexual identity. Wolf spiders have eight eyes as other spiders do and their primary pair lacks a reflective layer on the retina, but their secondary eyes have light-reflecting crystalline deposits that shine brightly in a beam of light. Unlike the primary eyes, these eyes have inverted retinas much like those of humans and other mammals. Because they have a very short focal length, wolf spider eyes don't change focus, therefore they enjoy excellent depth perception for objects at close range.

| A front view of a typical wolf spider, showing the arrangement of the eight eyes and impressive fangs. |

|

Wolf spiders are included in a larger group of similar creatures

collectively called hunting spiders. Lycosids, a more scientific

name for wolf spiders, are some of the swiftest of all, running

almost two feet a second, but at this speed after a few seconds

they are thoroughly exhausted. Like any good sprinter who values

his track shoes, wolf spiders gain traction with adhesive hairs

on the soles of their feet. Sprints are necessary mostly to

escape danger or to pursue prey. Once a victim is spotted, the

chase is soon over and the hapless locust or beetle is quickly

grabbed, injected with paralyzing venom, and its now-dissolved

tissues sucked out.

Like other spiders, lycosids extend their legs hydraulically by an increase in blood pressure, but contract them with muscles. If a wolf spider is injured enough to lose blood, it will run a short distance, then stop and be unable to move again.

Lycosids range widely throughout all kinds of habitats. I've watched one species construct silk-lined burrows in southern sand dunes, and there they spend the hot day, emerging at dusk to hunt for food through the night. This sand wolf binds excavated sand together with webbing, then carries it a distance from the burrow to be discarded, leaving no evidence of the spider's presence on the smooth surface.

I've found lycosids at very high altitudes, deep within sulfurous volcanic craters, and in luxuriant tropical rain forests. A half mile into the utter darkness of a Hawaiian lava tube I've come across completely eyeless wolf spiders, first discovered by another scientist only the previous year.

While inspecting our northern snow-freed garden early last spring, I saw a familiar figure scurry from my approach. It was a wolf spider, searching for prey in seemingly unseasonable weather. Good luck, I thought, until I saw a few insects in the air and several sluggish ants on the ground. The lycosid had timed its emergence from winter hibernation precisely right and was on its way to a successful hunting season—if only a sharp-eyed bird didn't get it first.

Female wolf spiders are very good mothers. Prior to egg laying they construct cocoons of webbing, creating first a disk of silk, then adding walls to form an egg receptacle. After eggs have been deposited in this, the chamber is closed and the whole case is wrapped in a loose mesh of webbing. She then carries the cocoon around holding it under the tip of her raised abdomen. A large similar-looking nursery web spider straddles her egg case and carries it underneath her body, clutched in her fangs, or chelicerae. When the young are sufficiently developed after two or three weeks, a mother lycosid opens the seam of the cocoon with her chelicerae and waits for the young to clamber upon her back where they hang onto her abdominal hairs. She carries several dozen youngsters for a week while they continue to be nourished by yolk within their bodies. After the first molt of their skin, they descend and go off on their own.

Should a youngster fall off its mother, it can live on its own but may attempt to crawl onto other wolf spiders if they come near, including males. If you are of the dirty tricks crowd, you can substitute a small ball of cork or cotton for the female's cocoon and she will carry it around for the prescribed length of time, then attempt to tear it open to release non-existent young. Her limited mental powers are sufficient to eventually tumble to the fact something is wrong, whereupon she discards the inanimate object. But to give them credit for a degree of maternal instinct, sand lycosids cooling off deep in their burrows will periodically take their egg sacs to the surface to warm up, thereby assuring continued development.

One common domestic species is known as the "purring spider," for it uses its anterior leglike appendages, the pedipalps, as drumsticks on a dry surface. It also has a hardened underside to its abdomen that is covered with knobbed hairs and when these strike the ground, they add to the complexity of sound production. In a quiet forest floor littered with dry leaves, a singing wolf spider can be heard twenty feet away. The song isn't much by our standards, for it consists of pulses or strumming in pairs, triplets or in a long series, each strum lasting less than a quarter of a second.

Despite how we evaluate them, songs in the animal world aren't sung for their beauty, but to convey information, such as claiming territory or during courtship. Although they are tone deaf, wolf spiders respond quickly and sensitively to distinctive "songs" that may consist of a brief burst of short pulses, followed by a long sequence of pulses that increase in rate and intensity, finally ending abruptly with a period of silence before the next burst begins. Each species has its own dialect consisting of sound intensity, pattern of pulses, and timing that speak of things important in the life of a wolf spider.

Lycosids respond to sound transmission through the substrate as well as airborne sound. Tapping with pedipalps and abdomen is not the whole story, however, for wolf spiders create still other sounds by rubbing "files" against "scrapers" located near their feet. The sound that results, known as stridulation, is found among a great many insects, other spiders, crustaceans, fishes, and even certain birds that rub their feathers together. One doesn't need vocal cords to produce sounds with meaning.

Spider songs have been recorded, but they can't compete with loons and whales and wolves in commercial appeal. The way to do it is to have an amorous male wolf spider strum on a thin piece of cardboard to which a small microphone has been fixed. The resulting pattern of pulses not only can be captured on tape, but rendered visible by means of a sonogram. Please don't ask me how to tell when a male wolf spider is feeling amorous—just provide a female nearby and listen to him sing.

Make no mistake: when a male wolf spider bursts forth in song, it surely is in the heat of passion. His heart rate may rise from around 50 to 175 beats a minute while singing to a female, or when warning away a male interloper. Sound familiar?

The author wishes to acknowledge the valuable contributions of David Richman, New Mexico arachnologist, who critically read the manuscript, and the research publications of R. F. Foelix, W. J. Gertsch, B. J. Kaston, R. Preston-Mafham, and T. H. Savory.

© 1999 William H. Amos

Comments to the author Bill Amos welcomed.

Editor's note: Other articles by Bill Amos (including those on spiders) are in the Micscape library (link below). Use the Library search button with the author's surname as keyword to locate them.

Published in February 1999 Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK