What we can discover on a spider's

leg

by Wim van Egmond

the Netherlands

|

|

| During

the last summer I have been making many 3D images of

spiders and insects. Since I was curious how they would

look under the microscope (and I am rather clumsy with

chemicals as well as a bit lazy) I ordered a series of

prepared slides. Maurice Smith sent me some very

interesting slides he sells in his on-line shop. (For

more information, see the bottom of the page) One of the slides contained a couple

of legs of a garden spider (Areneus diadematus). I

knew that just one leg contains many interesting

features. In this article I like to show you some of the

things you can find on a single spider leg.

Garden spider

eating a fly

(Click

image to view large version)

|

| The garden

spider belongs to the orb-web spider family (Araneidae).

It catches its prey with a large web. It does not rely

that much on its eyesight (which is rather poor) but more

on organs that can sense the slightest trembling of the

web. It is not strange that the legs contain many sensors

that can detect such vibrations in the web. It is easy to

demonstrate this by holding a tuning fork against the

web. The spider will leave its retreat thinking its the

beating of the wings of an insect. |

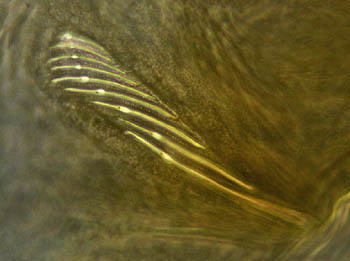

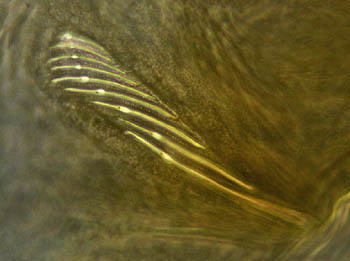

Tactile

hair, showing its texture The wide strand on the

background is a tendon (photographed with 25X obj.)

|

| But

what do these receptors look like? The spider's leg is

obviously very hairy. Almost all these hairs are sensory

hairs (in fact they are more like bristles), and act as

receptors that can detect touch and vibration. There are several types of sensory

hairs. You can identify them by the way they stand in

their socket. The large tactile hair above emerges

obliquely. There are also much smaller so called

trichobothria (they project vertically from their

socket). They are extremely sensitive to air currents or

low frequency air vibrations. Spiders can sense a flying

insect from several centimetres. Some spiders are able to

detect and catch a flying butterfly in mid-air.

There are also

chemosensitive hairs, the tip of the leg contains a

series of these hairs the spider uses to taste.

(Image

taken with 40X phase-contrast obj.)

|

|

|

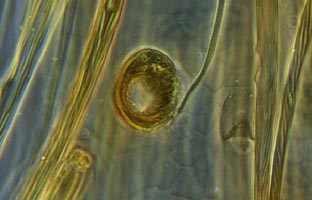

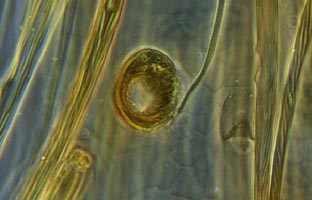

There is also a whole variety of

other receptors. So-called slit sensilla and lyriform

sensilla can be found all over the leg (most lyriform

organs are situated close to the leg joints.) With these

sensilla the spider senses it's own movements but they

also enable it to detect sound.

Each slit has

a thin membrane in which we can see a small dot. This is

a dendrite. This nerve cell detects deformation of the

slit.

(Image

taken with 40X phase contrast obj.)

|

Rather difficult to find is the

tarsal organ. It is a small spherical pit situated near

the end of the leg (the last segment called the tarsus).

They are supposed to detect odor as well as humidity.

(Image

of tarsal organ taken with 40X obj.

Cropped to show more detail)

Within the legs I could

also see the long tendons for the movement of the limbs.

The legs are stretched because they are under pressure of

body fluids. The spider only has to pull the cord to bend

the leg.

|

|

| But I saved the most spectacular

part of the spiders leg for last. The foot of a spider is

a very interesting object to study under the microscope.

You can see how the garden-spider is able to cling to the

threads of its web. The foot possesses two claws, one

downward pointing hook and several serated hairs. The

hooked claw grabs the thread and the serated hairs hold

the thread in the hook. There is a difference between web

building spiders and spiders that stalk their prey like

wolf-spiders and jumping-spiders. These don't possess the hooked claw.

But they often have tufts of hairs on their foot that

enable firm adhesion to a surface by means of capillary

force.

|

(Image

taken with 25X obj.)

|

| Detailed illustrations of how the

spider walks in it's web can be found in the Micscape

article Why a garden spider does not get

stuck in it's own web Since spiders are easy to find and

abundant it is not difficult to study these interesting

creatures. If you like to study a prepared slide like I

did, go to the OnView Shop to order spider legs or whole

mounts of spiders and insects.

|

Further reading:

Rainer F. Foelix, Biology

of Spiders (Harvard University Press)

Michael J. Roberts,

Spiders of Britain and Western Europe.

Spider websites:

Venomous

spiders

The slide was a Northern

Biological Supplies slide (N.B.S.) prepared by Eric

Marson

Comments to the

author Wim van Egmond are welcomed.

or visit Wim's HOME PAGE

Copyright

all material: Wim van Egmond 1999-2000

©

Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published

in the January 2000 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please

report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is

the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

WIDTH=1

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights

reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net.