Snow

Critters

by

Bill Amos,

Vermont,

US

Winter brings stress, crisis, behavioral and metabolic languor

to most wild creatures. Some, like summer birds and a few

butterflies in search of warmer climes, avoid harsh conditions by

leaving the north, while many resident animals hibernate in

winter-long torpor. For others, life is over by the end of

summer, their legacy left in protected eggs. Mammals, active or

asleep, grow thick insulating coats, and spiders and insects

descend from treetops to find shelter close to the ground.

Earthworms, toads, salamanders, and reptiles seek refuge as far

underground as possible where, with altered lifestyle, their body

fluids become resistant to freezing.

Birds that remain in the north cram themselves at our feeders.

Chipmunks, woodchucks, and bears sleep in their winter quarters,

and deer hunker down in protected forest glades. Grasshoppers and

field crickets vanish completely, leaving only their eggs in the

soil, while mole crickets (and moles themselves) dig deep beneath

the frost line. Although torpid wasps remain more or less

isolated in nests or sheltered crannies, bees in their hives and

ants in subterranean chambers huddle together where the slowed

metabolism of their combined body mass is sufficient to generate

a bit of warmth.

There is only one cardinal rule for animals in winter:

survive.

Winter not only brings rigors, it brings solutions too. In the

depth of winter, life is everywhere around us—on, in, and

beneath snow. Life of many kinds remains plentiful under

ice-covered ponds and streams. Snow and ice are superb insulators

for plants and animals underneath. Small creatures may not be in

evidence, but all we need do is look in the right places.

It is no surprise that moths and butterflies survive the

winter under conditions other than as adults; they exist as eggs

and in immature stages. What truly startles is the sudden

fluttering of a small moth across the snow on a mild February

day. You might even come across a conspicuous Mourning Cloak

butterfly hibernating in an unheated shelter. I discovered one in

my garage last winter.

The usual winter

evidence of moths and butterflies is either a dormant caterpillar

or a transformational pupa, bare or wrapped in a silken cocoon.

Larvae and pupae of all sorts of insects are found in forest

litter, in chambers deep in the earth, tucked into the inner

recesses of an old stone wall, burrowed into last summer's plant

stalks. If you seek insects in the rough bark of trees, search

the sunny side of a trunk, not the colder north side. Examine

knot-holes and woodpecker borings, as nuthatches do. Out in the

fields, each swollen goldenrod gall contains a tiny moth or fly

waiting to emerge in spring.

The usual winter

evidence of moths and butterflies is either a dormant caterpillar

or a transformational pupa, bare or wrapped in a silken cocoon.

Larvae and pupae of all sorts of insects are found in forest

litter, in chambers deep in the earth, tucked into the inner

recesses of an old stone wall, burrowed into last summer's plant

stalks. If you seek insects in the rough bark of trees, search

the sunny side of a trunk, not the colder north side. Examine

knot-holes and woodpecker borings, as nuthatches do. Out in the

fields, each swollen goldenrod gall contains a tiny moth or fly

waiting to emerge in spring.

A decomposing log on the forest floor not only is soft enough

to permit entry, but its bacterial decay creates warmth that

comforts as it provides safe haven for insects, spiders,

centipedes, millipedes, worms, and snails. Such creatures also

find protection in forest soil, an earthen incubator warmer than

soil in open meadows where the frost line plunges three or four

feet deep in our north country. A covering blanket of forest leaf

litter alone, with its labyrinth of insulating air spaces and

frosty cover, provides winter shelter for a wide array of small

active creatures.

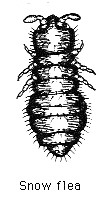

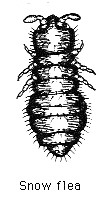

A few insects

are true denizens of winter. Snow fleas assemble at the base of a

tree where warmth creates melt-water on a sunny day. Hordes of

these tiny primitive springtails may blacken sunken patches of

snow, such as footprints and tire tracks. How do they survive and

what do they eat? Their active metabolism (also that of many

winter and high-altitude insects) is due to a natural antifreeze.

Micro-algae and decaying plant material constitute their staple

food. One kind of snow flea eats smaller springtails, but when

the sap rises late in winter, most species congregate near

outbreaks of the sweet flow.

A few insects

are true denizens of winter. Snow fleas assemble at the base of a

tree where warmth creates melt-water on a sunny day. Hordes of

these tiny primitive springtails may blacken sunken patches of

snow, such as footprints and tire tracks. How do they survive and

what do they eat? Their active metabolism (also that of many

winter and high-altitude insects) is due to a natural antifreeze.

Micro-algae and decaying plant material constitute their staple

food. One kind of snow flea eats smaller springtails, but when

the sap rises late in winter, most species congregate near

outbreaks of the sweet flow.

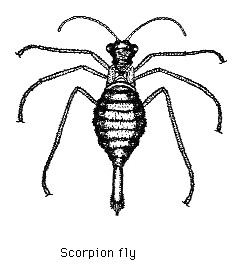

In early winter, I may discover scorpion fly larvae and pupae

around the base of a tree trunk, or in leaf litter. Later on,

fat-bodied, long-legged adult scorpion flies emerge and darken

patches of snow. Wingless, with a long pointed head, a scorpion

fly looks like no other fly we're familiar with.

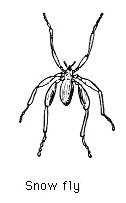

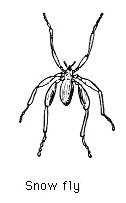

Another

flightless insect, the snow fly, is a crane fly whose summer

relatives resemble giant mosquitoes. Not the winter species,

however, which lacks wings and has long fuzzy legs. Most of the

winter it remains in leaf litter or under logs and stones, but on

mild, sunny days, snow flies crawl over the snow in search of

mates. Resembling little spiders, it takes a sharp eye to

determine what they really are.

Another

flightless insect, the snow fly, is a crane fly whose summer

relatives resemble giant mosquitoes. Not the winter species,

however, which lacks wings and has long fuzzy legs. Most of the

winter it remains in leaf litter or under logs and stones, but on

mild, sunny days, snow flies crawl over the snow in search of

mates. Resembling little spiders, it takes a sharp eye to

determine what they really are.

If I visit our ice-rimmed brook and turn over stones in the

swift frigid current, I'll surely find stonefly nymphs. It is

even more amazing when large stonefly adults emerge into winter

air to fly, feed, and mate as a natural part of their life cycle.

It is said that some years they even swarm and alight in huge

numbers upon snow-laden trees, although I've seen no more than a

few individuals on my forays.

Immature insects of many sorts are present in an icy brook,

with mayfly nymphs and water pennies (beetle larvae) as the most

predictable. They and stonefly nymphs find plenty to eat by

gathering dead insects and plant fragments that whirl downstream

in the swift, swollen current. This is not a time of stress for

them, because cold-adapted brook insects are present throughout

the year. As we brook-dabblers know well, the summer temperature

of a clear little upland stream still carries a touch of winter.

Low temperatures are a problem for terrestrial insects if

excess moisture is present, so many species rid themselves of as

much body water as they can before the onset of winter,

converting what remains into a form that is incorporated into

cell substance, thus resisting freezing and crystallization that

destroys tissues.

In northern New England each kind of insect copes with winter

differently. If disturbed in their winter quarters, some stir

themselves at once, while others require hours of warmth before

they can move. With the onset of autumn, many insects are frantic

to complete a portion of their life cycle: mating, laying eggs,

or eating their last meal as a larva before metamorphosing into a

pupa. Some settle into the first available protected spot, while

others seek exactly the right sort of place— a certain kind

of plant stem to bore into, for example—before coming to

rest. Numerous adult insects die after ovipositing, their kind

surviving through winter only as tiny protected eggs.

While winter is the peak season for snow insects and presents

few problems for brook creatures, the rest of the insect world

remains quietly unseen. Inactivity leading to dormancy may begin

as early as late summer in some species, but for others

December's cold is required to put them into a torpid state. Name

your insect and it is here—somewhere.

Much the same can be said for spiders. Some adults survive by

preparing a winter nest of silken webbing under loose bark within

which they are insulated from the cold. Other spiders die in

autumn, but their kind lasts through the winter as undeveloped

eggs. In several species, young spiderlings hatch out, then

remain in a communal webbed egg sac through the winter. Those

spiders that hibernate in leaf litter and in rock piles often are

not deeply asleep, and on mild winter days may crawl about in

search of insect food that is plentiful and easy to secure in its

dormant state.

Young spiders often take refuge in moss, and should you bring

a clump into the house, be prepared to have spiderlings and many

other little hibernating creatures crawl out as warmth unlocks

their muscles and increases their metabolism and consumption of

oxygen. If you insist on poking about in moss—or leaf litter

or under rocks—you will surely also come across hibernating

land snails, deeply withdrawn into their shells and protected

with a mucus plug or, if so-equipped, behind an operculum, a

"door" expressly designed for protection at any time of

year.

Last month, within an hour after bringing our just-cut

Christmas tree in from the cold, little critters skittered across

the living room floor. They were gathered in a jar and taken

outdoors to a nearby treeline where I brushed away snow and

scooped up a bit of leaf litter, dumped the jar's contents into

the depression, then covered it with a thick layer of leaves.

Christmas is a time to be particularly considerate of others,

even the least of those amongst us, and it seemed to me that the

gift of life was the least I could do for small creatures rudely

awakened from their winter sleep.

© 1999 William H. Amos

Comments to the author Bill

Amos welcomed.

Bill Amos, a frequent contributor to Micscape, is a

retired biologist living in the wooded hill country of Vermont in

northern New England. He is an active microscopist and author of

many natural history books and articles.

Editor's note: Other articles by Bill Amos

are in the Micscape library (link below). Use the Library search

button with the author's surname as keyword to locate them.

© Microscopy UK or their

contributors.

Published in January 1999

Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

WIDTH=1

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights

reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net.

The usual winter

evidence of moths and butterflies is either a dormant caterpillar

or a transformational pupa, bare or wrapped in a silken cocoon.

Larvae and pupae of all sorts of insects are found in forest

litter, in chambers deep in the earth, tucked into the inner

recesses of an old stone wall, burrowed into last summer's plant

stalks. If you seek insects in the rough bark of trees, search

the sunny side of a trunk, not the colder north side. Examine

knot-holes and woodpecker borings, as nuthatches do. Out in the

fields, each swollen goldenrod gall contains a tiny moth or fly

waiting to emerge in spring.

The usual winter

evidence of moths and butterflies is either a dormant caterpillar

or a transformational pupa, bare or wrapped in a silken cocoon.

Larvae and pupae of all sorts of insects are found in forest

litter, in chambers deep in the earth, tucked into the inner

recesses of an old stone wall, burrowed into last summer's plant

stalks. If you seek insects in the rough bark of trees, search

the sunny side of a trunk, not the colder north side. Examine

knot-holes and woodpecker borings, as nuthatches do. Out in the

fields, each swollen goldenrod gall contains a tiny moth or fly

waiting to emerge in spring.  A few insects

are true denizens of winter. Snow fleas assemble at the base of a

tree where warmth creates melt-water on a sunny day. Hordes of

these tiny primitive springtails may blacken sunken patches of

snow, such as footprints and tire tracks. How do they survive and

what do they eat? Their active metabolism (also that of many

winter and high-altitude insects) is due to a natural antifreeze.

Micro-algae and decaying plant material constitute their staple

food. One kind of snow flea eats smaller springtails, but when

the sap rises late in winter, most species congregate near

outbreaks of the sweet flow.

A few insects

are true denizens of winter. Snow fleas assemble at the base of a

tree where warmth creates melt-water on a sunny day. Hordes of

these tiny primitive springtails may blacken sunken patches of

snow, such as footprints and tire tracks. How do they survive and

what do they eat? Their active metabolism (also that of many

winter and high-altitude insects) is due to a natural antifreeze.

Micro-algae and decaying plant material constitute their staple

food. One kind of snow flea eats smaller springtails, but when

the sap rises late in winter, most species congregate near

outbreaks of the sweet flow.  Another

flightless insect, the snow fly, is a crane fly whose summer

relatives resemble giant mosquitoes. Not the winter species,

however, which lacks wings and has long fuzzy legs. Most of the

winter it remains in leaf litter or under logs and stones, but on

mild, sunny days, snow flies crawl over the snow in search of

mates. Resembling little spiders, it takes a sharp eye to

determine what they really are.

Another

flightless insect, the snow fly, is a crane fly whose summer

relatives resemble giant mosquitoes. Not the winter species,

however, which lacks wings and has long fuzzy legs. Most of the

winter it remains in leaf litter or under logs and stones, but on

mild, sunny days, snow flies crawl over the snow in search of

mates. Resembling little spiders, it takes a sharp eye to

determine what they really are.