|

Stentors

by

Howard Webb (St. Louis, MO,

USA)

|

Introduction

Stentors are a unicellular ciliate, noted for their trumpet

like shape (hence the name stentor, after the Greek herald of

the Trojan war). Stentors are one of the largest single celled

organisms, occasionally being several millimeters in length.

Where to Find

Stentors are usually found in the calm water of ponds and

lakes, usually near the surface attached to leaves or twigs.

While they are capable of free swimming, they are most often

noticed clustered together in small colonies. These particular

stentors were found in a cluster attached to the side of a

collecting jar. I had gathered a few twigs from shallow water

(I was actually looking for hydra), and they became apparent

after about a week. I used a small pipette to scrape the

colony from the side of the jar and transfered it to a slide

for observation.

Normally it takes a bit of hunting to find stentors, though I

have on occasion found them so thick that a sample is tinged

green with their presence.

Anatomy

Most notable of the stentor is the 'crown' of cilia

surrounding the trumpet 'bell'. This crown is not a complete

circle. These cilia are used to create a current of water from

which it sweeps food. Every little while, the stentor will

close up the cilia crown and contact, bringing the food within

its cell structure.

The crown is not the only cilia on the stentor, its whole body

is covered with shorter cilia, which are used for locomotion

when free swimming. When moving, the stentor is contracted

into an oval or pear shape.

Being single celled, there are no separate parts which make up a

"mouth" or other organs. For digestion, the cell wall

envelops the food, and separates to form a round bubble like

"vacuole" within the cell. After the nutrition from the

food is extracted, this vacuole moves to the outer cell wall

and 'pops', evacuating the remaining contents. Since

stentors have a cell density higher than the water in which

they live, osmotic pressure causes water to transport into the

cell. The stentor cell actively collects this excess water

into a vacuole, and expels it; thereby maintaining the

internal fluid density.

Behaviour

Stentors, like most ciliates, are filter feeders; passively

eating whatever happens to be swept in their direction. They

normally eat bacteria and algae, though large stentors are

reported to opportunistically eat rotifers or anything else

that they can catch.

Images

|

|

|

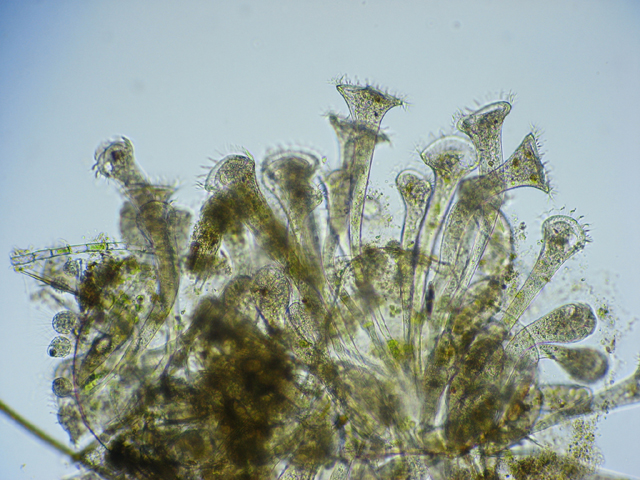

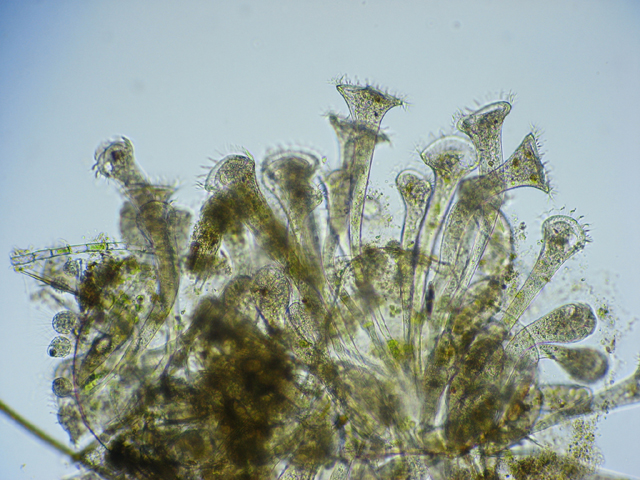

Unlike some vorticella, where the whole colony

is connected as a single organism, a colony of

stentors is a group of individual organisms

which just happen to be located together.

This colony looked like a spot of

mold beginning to form on the side of the

collecting bottle. I pushed it loose with a

pipette, and transferred it to a microscope

slide.

|

Stentors

|

|

|

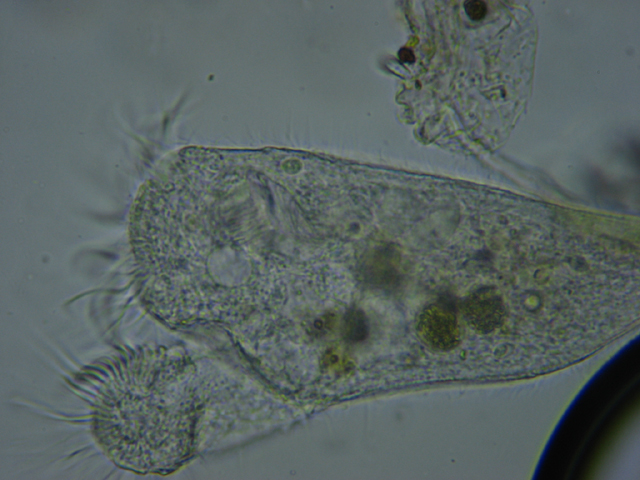

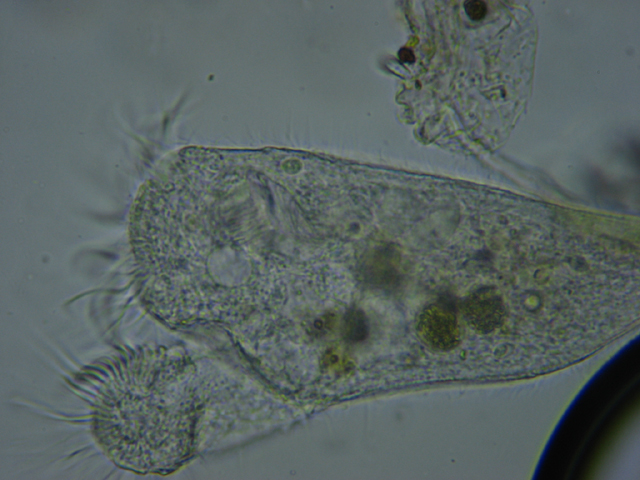

When stentors are

traveling, they are not in the typical trumpet

shape, but contract into a more oval shape.

The cilia on the trumpet bell closes up, and

the cilia on the body are used for locomotion.

The illuminator was moved down to give more

contrast (and also shows up more background

artifacts - compare to the next photo).

|

|

|

|

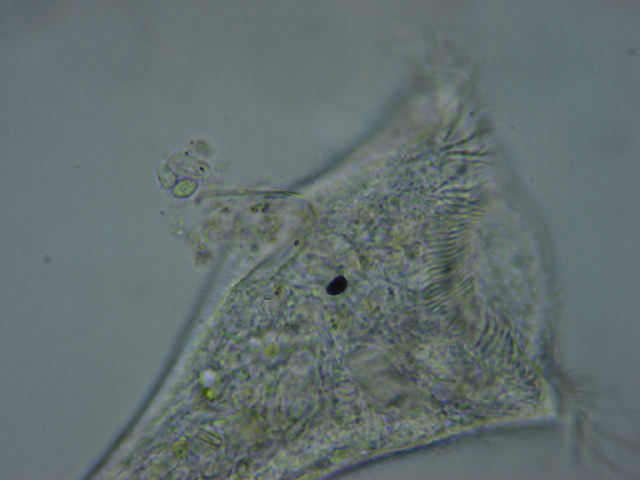

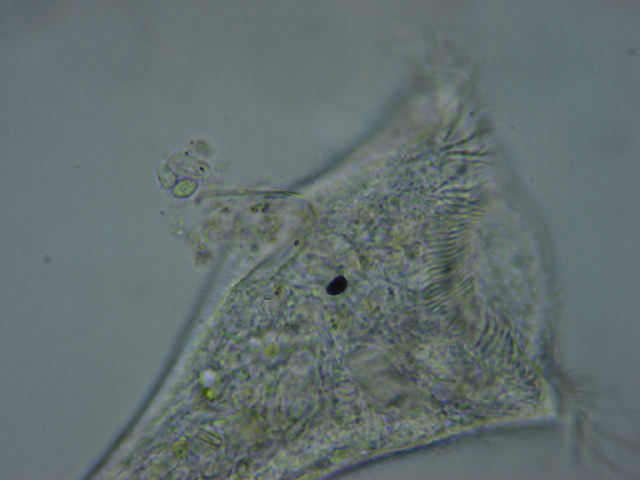

Another stentor in motion.

|

|

|

|

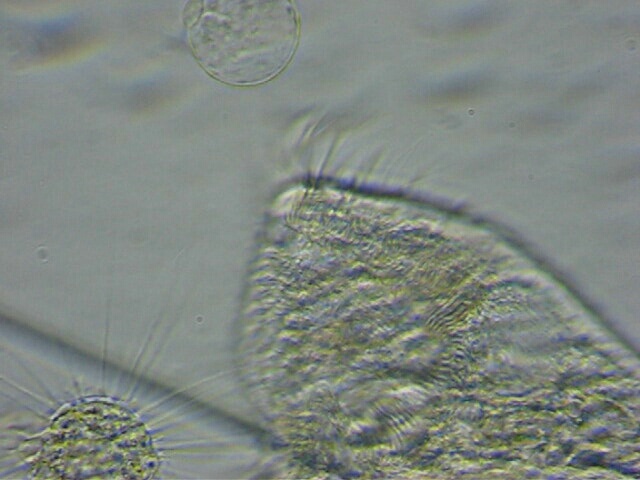

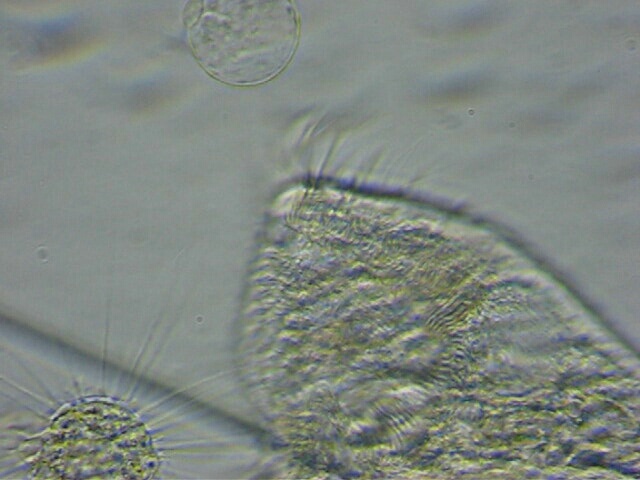

Stentors have a rather complex reproductive

cycle. Here a stentor undergoing division.

|

|

|

|

Food vacuole being evacuated.

|

|

|

|

Movie of the cilia around the bell of the

stentor. The bell is more than a

simple round shape.

|

|

|

|

Movie showing water current produced by cilia,

and contractile vacuole

shrinking.

|

Technical Details

Environmental Conditions:

Water temperature:23C

Depth: collected near the

shore, at less than 6 inches depth

Secchi visibility: 2 meters

Location: quarry at

Whitecliff Park, Crestwood, MO (lat: 38.5561, long:

-90.3688 (NAD83/WGS84)). The park contains an old, abandoned

quarry, which is probably one of the deeper bodies of water in

the area. The quarry is generally closed to the public, though

the city has been kind enough to give me access.

Microscope: Bausch & Lomb monocular, 10x ocular,

4x, 10x and 40x objectives.

Illumination: Luxeon K2 LED

Camera: Canon A540 (6 megapixel)

Software: Photoshop Elements, VirtualDub

References

Vance Tartar, The Biology of

Stentor, Oxford, New York, Pergammon Press,

1961

This is a classic work. Most of the text describes

studies of slicing and dicing stentors, and observing their

regeneration; though there is a thorough coverage of their

anatomy and behavior, as well as culture techniques.

Comments to the author

are welcomed.

© Microscopy UK or their

contributors.

Published in the July 2007

edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the

Micscape

Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at

http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/