|

An Assortment of Marine Invertebrates From the Philippines Part 1: Echinoids by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Over the past 10 years or so, I have occasionally ordered a variety of marine specimens from a couple of dealers in the Philippines. What I order at any particular time depends upon my consuming passions at the moment. For a considerable time, I was obsessed with sea urchins and starfish and, more recently, with chitons and sponges. These specimens have a special interest for me because they offer not only variety, but being tropical organisms, they are generally quite different from any of the other specimens which I have access to. In this gallery/essay, I want to share some of these with you to give you an idea of some of the wonders and marvels that one can investigate using dried specimens. First, I’ll show you a couple of Styrofoam trays of sea urchins and then we’ll zero in on selected specimens for a closer look.

Here you can get a glimpse of the variety in types of spines and color. First, let’s look at a closeup of Micropyga tuberculata. Two distinctive features of this species: 1) the test is somewhat flattened and the color of the spines is often a brilliant red. This species has some unusual tube feet which expand to terminate in a large disk. It also has an unusual organization on the ambulacral plates of pore-pairs.

Here is another view which shows the flattened test.

Then we have an urchin with really “crazy” spines, Psychocidaris oshimai. These are among the most unusual spines among all the echinoids.

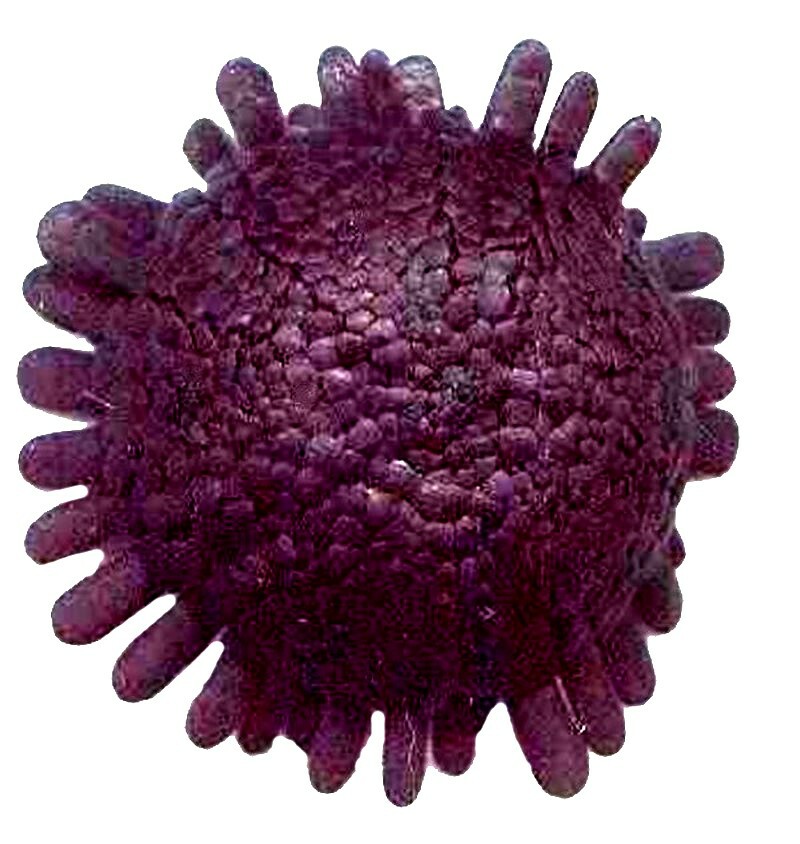

Next is a large urchin shell of an unidentified species from which all the spines have been removed, revealing a rich purple color with the typical pentagonal pattern with the double rows of openings for the tube feet.

Surprisingly, the spines in some species, especially tropical cidaroids, are frequently invaded by other organisms as is the case with the tiny barnacles on this specimen of Stereocidaris granularis var. rubra.

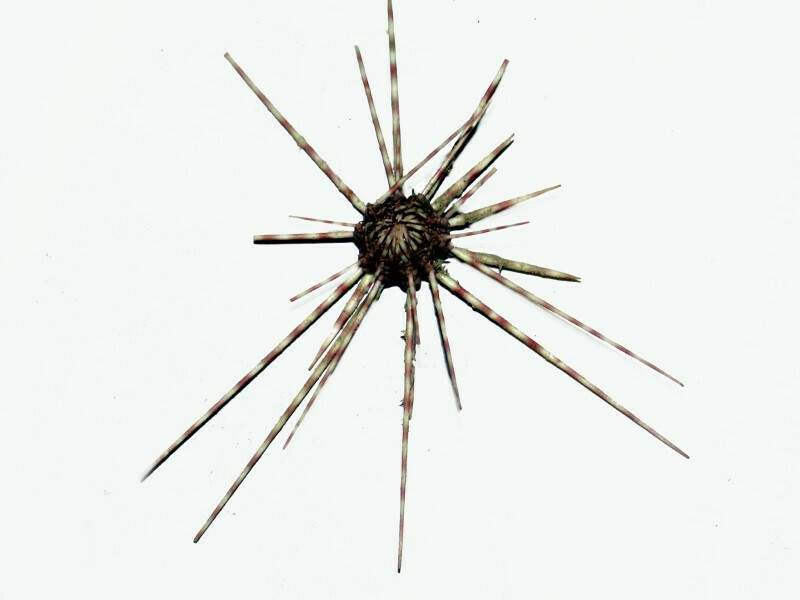

Some species, however, have spines that are acicular (needle-like) and therefore are difficult to colonize, as is the case with Astropyga radiata which is one of the Diadematoida. You will notice a very distinctive pentamerous pattern in this species and also some small white spheres. The latter are infuriating artifacts of the manner of packing by the dealer; that is, they are remnants of “pearl styrofoam”. It took hours to remove the hundreds of “pearls” which surrounded this specimen for shipping. I contacted the dealer immediately to let them know that I would no longer accept any specimens packed with that material and we have had no problems since.

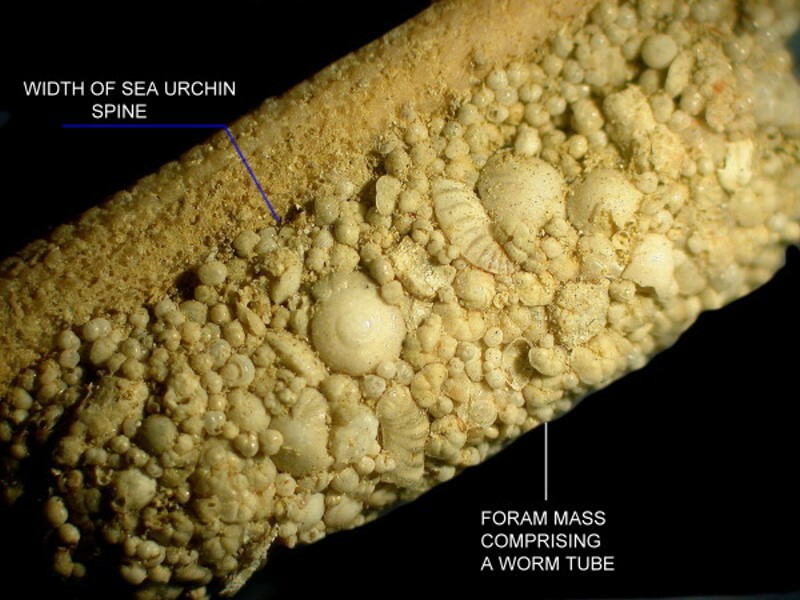

On certain species, these infestations can become very significant indeed. This next example, however, is not barnacles, but foraminifera surrounding a worm tube.

And here’s a closeup.

While we’re looking at spines, let’s consider a few more that are quite unusual. Clearly the character of spines is sometimes a function of environment and this is certainly the case with Podophora atratus. It is almost always found in areas where there is heavy surf action and thus it has evolved flattened spines as a protection.

A quite wonderfully whimsical spine is to be found on Goniocidaris clypeata. A number of possible descriptions occur to me: a spherical collection of trumpets, a series of inverted mini-umbrellas, or tiny bathing basins for passing plankton. I do have a couple of specimens in which a “basin” or two have been inhabited by a small sponge. Note that the secondary spines are quite regular in their appearance and the incredibly small tertiary spines in the center look rather like stacks of needles.

A view of a different specimen reveals a small brachiopod, at the upper left, which has attached itself.

A closeup of one of the spines reveals to us that there are rings around the rod and, in this example, near the edge of the bowl, the curved remains of the shell of a very wee tube worm.

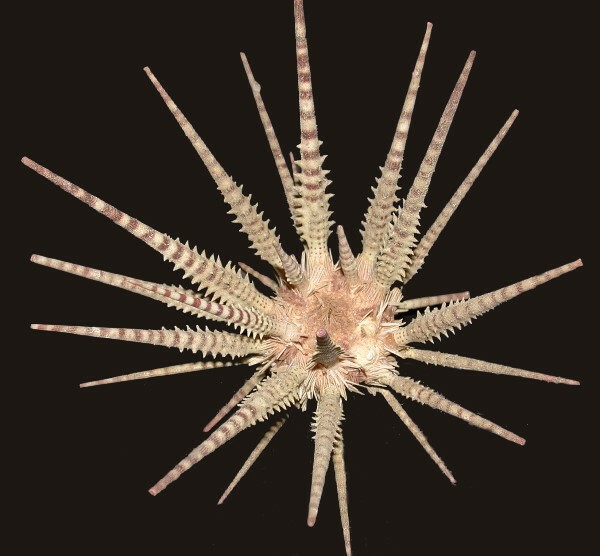

Next up is a specimen with lovely, colored, striped spines. This is a specimen of Prionocidaris baculosa.

Within this same genus, we can find interesting variations in the character of the spines. Here is a specimen with very spiny spines, Prionocidaris australis.

Some species with quite small tests can have remarkably long spines and this is in general true of the genus Coelopleurus whose spines can be more than 3 times in length the diameter of the test.

The tests of this genus are especially attractive and a relatively recently discovered species, C. exquisitus is especially beautiful.

Quite a number of echinoids have stubby, relatively short spines and Eucidaris tribuloides is a good example.

Sometimes just the simple variation of shadings can produce a very striking and pleasing pattern. Here the combination of browns and beiges is very attractive indeed in this specimen of Pseudoboletia maculata.

As a conclusion for this part, I’ll show you a specimen of an irregular echinoid. All of the ones we looked at up to this point were regular urchins. The irregular ones in curio and craft shops are almost always “cleaned;” that is, bleached to remove the spines and to make them “Persil white”.

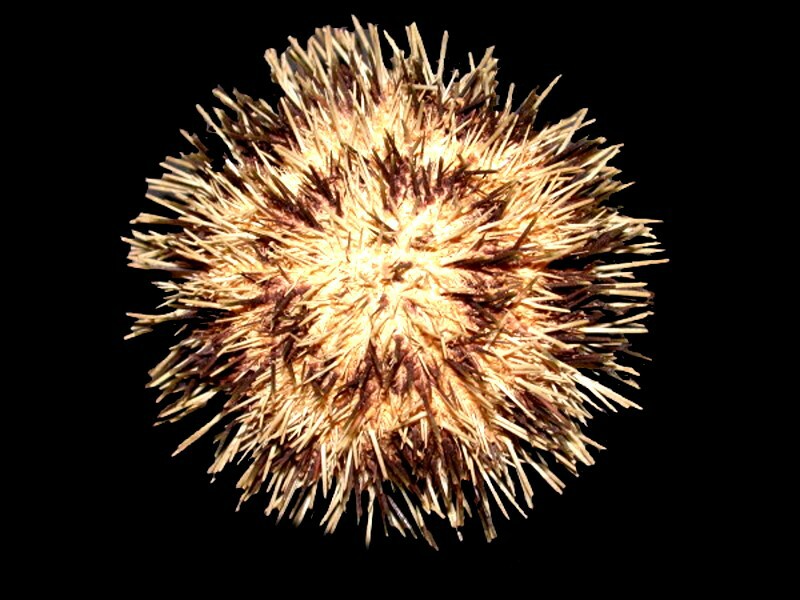

This is a specimen of Maretia and, as you can see, it has an incredible number of spines (if you don’t think so, just try counting them!).

In Part 2, we’ll look at some organisms from other groups.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the July 2017 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .