It was a cold, rainy, and hectic day.

Despite all my efforts I had missed my scheduled flight back

home. Without any intention of buying anything, I looked

around some shops which were still open, and aimlessly

entered a small display area where only postcards and some

new year calendars were sold. I bought one card, which had

the script shown

below on its back cover:

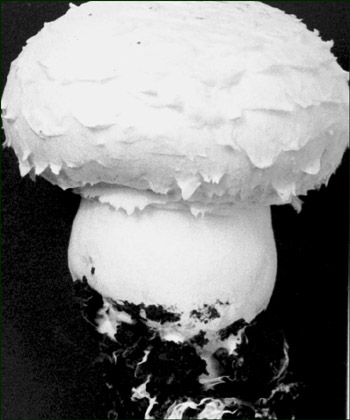

Afterwards, I sat down, as I had to wait over two hours for the last flight. Then, I carefully looked at the card through its transparent envelope. It was a beautiful, handmade illustration of a mushroom; a fairy mushroom with a red cap showing white spots (see image below). Suddenly, the disturbing feeling that I had always neglected fungi, made me ashamed for a while. How could I neglect fungi? Aren’t they living organisms - as are mice, cats, flowering plants, amoebae, bacteria and human beings?! Sure, fungi are living organisms; some may be microscopically small and not directly visible. But a certain number of them are macroscopic and form fruiting bodies in different shapes, sizes and colours. Some are even edible and delicious too, although some fungi can be very dangerous to health and even deadly.

The baker needs yeast to make bread, the brewer needs yeast to make beer; fungi are also essential in winemaking and for antibiotics. Fungi are vital to us for so many things and Nature needs them as well. Fungi have always been indispensable to our biosphere!

White Button Mushroom, Agaricus bisporus, during commercial cultivation.

This is a macro fungus with a cap size of about 5 cm.

The fungi shown above is a fruit-body arising from the mycelium. The basal part of its stipe, which is still carrying remnants of the mycelium and casing, will be cut and discarded.

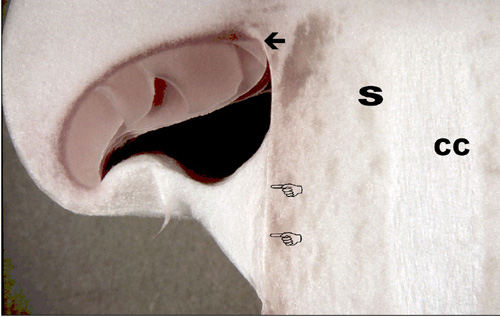

Of course, our interests will be immediately focused on the internal structure of this macroscopic Basidiomycete fungus. One of the usual methods to appreciate such structures is to bisect the fruit-body from its central point through the cap and stipe. In technical terms this is a vertical median section that provides us with two symmetrical halves. Let’s look at the left part of a sectioned fruit-body (shown below) and try to identify tissues and organs that may be visible.

Do you recognize the gills (arrowed above), cap and stipe (S)? Gills produce the basidiospores of A. bisporus. The surface covering of the gills is called the hymenium. It consists of a row of specialized cells called basidia. These cells are determinants of the large group of fungi classified as Basidiomycota. Beneath the gills there is a cavity, the hymenial chamber, which is still closed in this illustrated sample. When a fungus matures, this cavity opens and basidiospores are shed to germinate into new mycelia.

Nowadays, commercial mushroom cultivation has become an industrial scale concern, although initiating a new cycle of a fungus from spores remains a domain of the laboratory. Two pointing fingers in the image above show the zone called the annulus and the whitish tissue is the veil which will rupture when a fruit-body is mature. The stipe, cap, annulus, veil, gills etc are anatomical features very useful in the identification of the genera and species of mushrooms. Other microscopical and genetic properties are also important in identification. When a fruit-body is very young it is called a primordium. When it develops and its veil opens, it is called a mature, open mushroom. Most white button mushrooms you can find in markets are young, developing examples of closed ones. Open mushrooms are prone to different kinds of diseases. Mushrooms, like any living organism, inevitably die and decay after playing an invaluable role in nature. (See ref. 1).

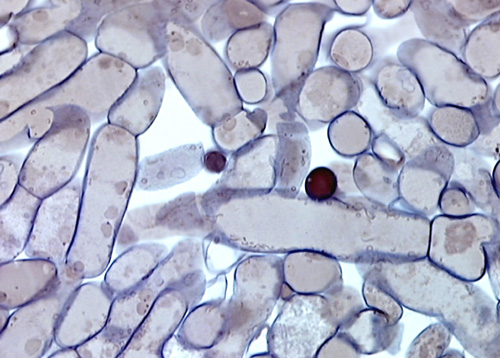

Microscopically, fungi

have a filamentous structure. Such filaments are called hyphae.

Cells of fungal tissues are thus tubular and are delineated

by a chitinous cell wall. Fungal cells may frequently have

many nuclei in their cytoplasm. Around the hyphae of fungal tissues there is always empty looking air space, the

so-called interhyphal space. These spaces are, of

course, not empty and serve for the continuity and structural

integrity of the tissues. The accumulating gases, the

extracellular matrix, and water-based materials are all

there. Many chemical signals, needed for development for

example, are transported along the external side of the

hyphae. In the high quality image above, made from a 2

micrometer thick tissue section stained with Safranin

-Toluidine blue - Haematoxylin, the cell organelles

mentioned, such as cell walls (darkly stained) and nuclei

(yellow-brown round structures with eccentrically situated

nucleoli which are

dots stained dark blue), and other cytoplasmic

substances are visible. Note the empty looking interhyphal

spaces outside the hyphae.

The image above features three specimens of Amanita muscaria found around a pine tree, on a rainy September day in the Netherlands: the left hand specimen is a developing primordium with still closed hymenial chamber, at the center an open and mature one showing radiating gills and a very young primordium on the right.

This card, illustrating an Amanita muscaria (fly agaric), ignited a love at first sight, and it became one of my dearest treasures. When I think about ‘interaction in Nature’, I first think of fungi. If I look carefully around me, I’ll always find nice examples of the interaction between many living organisms and fungi; from the one-celled to multi-celled, from microscopical to macroscopical in size. Life - isn’t it a continuous interaction between organisms?

Comments to the author M. Halit Umar are welcomed.

Editor's note: To complement this article Jan Parmentier has kindly written Attractive But Deadly, which looks at why some fungi are so poisonous, using three infamous examples.

References

(1) Umar & Van Griensven. (1997). 'Morphological studies on the life span, developmental stages, senescence and death of fruit bodies of Agaricus bisporus'. Mycological Research 101 (12): 1409-1422. ('Mycological Research' is the scientific Journal of the British Mycological Society.)