Many years ago, I was given several microscopy books written at the beginning of the last century and published in Great Britain. The authors compared 'home-grown' microscopes, notably Watson stands, with the new 'Continental' types of Leitz and Zeiss. Not surprisingly, they considered the stability and range of controls of the British stands to be superior. From the photographs, the characteristic tripod profile of a Watson 'Edinburgh' stand seemed to me to be the perfect mix of form and function.

When the time came to purchase a second hand microscope for my own use back in 1975, I chose a Leitz polarizing stand of 1960's vintage. I have used this microscope for almost 30 years to take crystal photomicrographs and have never regretted the purchase. More recently I have obtained a Zeiss 'WL' stand for general microscopic use. In the back of my mind however, the dream of using an old Watson stand has never faded.

One day while searching on eBay, I noticed that the photograph of an old microscope lamp being sold also contained part of a strange, very large old Watson microscope. On a whim, I emailed the lamp seller a question about the microscope and was rewarded for my interest with information and pictures. The stand was a circa 1918 Watson "Mint" Metallurgical which had originally been ordered with complete transmitted light functionality as well as its normal reflected light capabilities. The owner offered to sell it to me for what I considered to be a very reasonable price and FedEx flew it across the Atlantic and delivered it to my door three days later.

The Stand

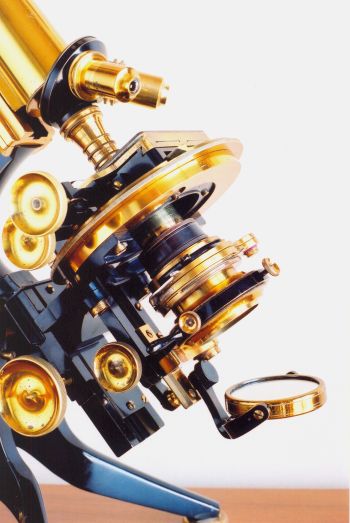

What struck me first was the massiveness of the stand and the excellent condition considering its age. My small collection of microscopes contains a 1908 Watson FRAM and a 1915 Watson Edinburgh "H". The Metallurgical towers over both (18" or 46 cm as shown) and is a real handful (7.4 kg or 16 pounds). The photograph shows all three for comparison with the Metallurgical on the left and FRAM on the right.

As can be seen in the photographs below, the stand is a greatly enlarged version of the Edinburgh type where the tripod legs span about 8.5 inches.

The coarse focus adjustment is by diagonal rack and pinion with the ability to control the force with which the pinion pushes on the rack. The fine focus is by horizontal lever with extremely delicate control. The finest graduation of the head is 1/33000 of an inch resulting in one complete rotation moving the body by 1/330 of an inch. This is the best fine focus of any microscope that I have used, particularly at high magnifications. Watson's unique compensating system of slots and bolts on all rackwork allowed me to easily adjust all focussing and stage controls to provide very smooth operation.

The circular stage is provided with the normal Watson horizontal and vertical mechanical controls and allows rotation through 270 degrees. It is fitted with a sliding bar containing the stage clips to hold a slide. There are verniers on the side and bottom of the mechanical stage reading to 1/10 mm.

For metallurgical use the entire stage and substage assembly can be raised or lowered by means of a rack and pinion in large dovetailed slides. This allows the metallic specimen to be focussed without moving the eyepiece-objective tube. The alignment of the illumination and apparatus to reflect it onto the specimen is not disturbed as the polished specimen is brought to focus.

In this particular stand, a large and complex substage apparatus is fitted. In addition to the normal centering and focussing controls, the entire substage can be swung away from the stand. As well, the top half of the condenser containing the optics can be rotated out of the optical axis leaving only the iris diaphragm. Because the stage thickness is so great, a threaded spacer is provided to allow certain optical condensers to get close enough to the slide.

The mirror is mounted on a triple pivot assembly to the rackwork that allows the stage to be moved up and down. This effectively allows the mirror to be aligned to the optical path without the chance of colliding with the substage rackwork when it is moved down. Even with this ability, it is still difficult to remove the substage assembly from the microscope.

In order to use the instrument as a reflected light microscope the normal objective carrier is removed and replaced by a vertical illuminator. This consists of a series of condenser lenses and an iris diaphragm. The light is reflected onto the specimen by a coverglass held in position by a well designed system of brass strips and bolts. I believe that the original light source was electric based upon the extremely old transformer mounted inside the mahogany box that housed the microscope. By experiment I found that the light source from my more modern Zeiss WL stand could be adapted to fit into the end of the vertical illuminator. The illumination produced is fine for optical use but a more intense light source would be required for photomicrographic use.

The Optics

The microscope came equipped with three Watson Holoscopic Eyepieces (x5, x7, x10) of the top hat variety that Watson refers to as their 'capped form'. These eyepieces are essentially Huyghenian, but allow the distance between the lenses to be changed. With ordinary low power objectives, the top is pushed in, reducing the distance between the lenses. With Holoscopic or Apochromatic objectives, the top is pulled out, maximizing the distance between the lenses.

At the moment, I have a variety of Watson objectives that are used with the stand. In optical terms, the best are two Holoscopic of focal length 8 mm and 6 mm and an amazing 4 mm Apochromat. The Apochromat rivals the best of my more modern Leitz and Zeiss objectives of similar focal length, although it certainly does not share their flat field capability. These objectives are designed for a variety of tube lengths from 200 mm to 250 mm. With the tube pulled out to the 250 mm length, the microscope is a neck stretching 23 inches high!

In addition to the objectives, the microscope has three Watson condensers: a 'Universal' Holoscopic achromat n.a. 1.0 of focal length 0.4 in., a 'Parachromatic' n.a. 1.0 of focal length 0.29 in. and an Abbe n.a. 1.2. All three allow the top to be removed for low power use.

Using the Microscope

I suppose that an amateur microscopist is somewhat like a sports car enthusiast. Even though a more reliable, newer car sits in the garage, he or she spends hours in the countryside driving an older, less reliable vehicle in order to experience a bit of automotive history.

Using this old microscope is just plain fun! The beautiful engineering is more obvious than in more modern examples, since moving parts are not hidden behind large expanses of grey metal or (shudder) plastic.

On the plus side, the focussing adjustments of the Metallurgical are quite the equal, in practical terms, of more modern stands. With the best old objectives the resolution is comparable in the center of the field of view. The 'Universal' condenser seems better optically than any of my more modern condensers.

On the minus side, there can be no doubt that modern microscopes with their coated flat field optics and binocular view make an evening of slide viewing a less arduous task. I admit that I have become lazy and expect the convenience of built in Kohler illumination. It does take some time to get everything properly aligned with this microscope even with transmitted illumination. Setting up for incident illumination is not a task for the faint hearted!

When all is said and done however, using the microscope is an experience that I enjoy immensely. The fortuitous sighting of this old Watson and the willingness of the previous owner James Battersby to relinquish it are distinct high points in my microscopical adventures.

All comments to the author Brian Johnston are welcomed.