The six slides which are the standard 3x1 inch with diamond inscribed labels.

|

Six whole mount insect slides: With notes on imaging routes for large slides with a 35mm film scanner, DSLR with macro lens and near IR. by David Walker, UK |

The skill, patience and dexterity that some Victorian mounters demonstrated when arranging and mounting whole insect slides is very impressive. Named examples by the most famous mounters do come up for sale but they often attract top prices.

The gallery below shows images of six whole insect slides by an unknown mounter but they have been prepared to a high standard. With large mounts I frequently enjoy the 'bigger picture' just with a 10x loupe used for viewing 35 mm film slides and using a 35 mm slide viewing light box. This allows armchair enjoyment while browsing the books or surfing the web to learn about the subject. Smaller features can subsequently studied with the microscope.

The older slides also have a certain tactile pleasure in just handling them, with their often thicker glass, bevelled edges, mounter's own handwritten script and wondering what long history of owners there have been since they were made.

Note on imaging: The larger mounts can often prove the trickiest to digitally photograph well; the typical 2x - 3x compound microscope objective combined with the cropping factor of some digital cameras will require multiple stitching to image the whole insect. The depth of focus at sensor plane is smallest for the lowest powers thus requiring critical focus and high performance objectives to achieve quality results. Evenly illuminating subjects to photographic standards at the lowest power can also be tricky with the typical Köhler illuminator using a small filament bulb as light source.

The lowest power on a stereo would give a wider field but unless a high quality model is owned, images taken using a stereo are invariably poorer than images taken using compound microscope objectives.

However, the increasingly affordable high resolution flatbed scanners and dedicated film scanners offer an easy route for imaging large subjects if such a scanner is available. My A4 Plustek flatbed scanner is ancient but does passable scans of larger slides for web page images (see Topical Tips 3); the modern hi-res flatbed scanners especially those with a 35 mm slide scanning function should do much better print quality imaging. The dedicated 35mm film scanner can do even higher quality imaging in seconds as they have been designed to extract the finest detail in the small imaging area of 35 mm film and this is the route I used for the whole insect images below unless stated otherwise. The scanner was a Minolta Dimage Scan Elite 5400 dpi; safe ways of supporting the microscope slides in the film holder and scanning tips are described in a previous article.

Buying a dedicated film scanner for this sort of work alone can't be justified, the author uses the Minolta for digitising 35 mm slides and home developed B/W negs. The most cost effective way to buy one is secondhand off a dealer or eBay. As many photographers buy them, realise how much work is involved in digitising large numbers of 35 mm slides and sell them, often mint for half the new price (e.g $375 as new on US eBay is not atypical). Buying one model behind current model, scanners can sometimes be a third of original new price.

The

six slides which are the standard 3x1 inch with diamond inscribed labels.

Image

Gallery using a Minolta Dimage Scan Elite 5400 dpi 35 mm film scanner

Heading for each is as stated in the diamond scribed script on each slide.

Note

that detail in the original scan is lost on drastic resizing for the web page;

the master scans can be up to 5000x3500 pixels despite the insect not filling the

35 mm scan area.

Images essentially as scanned apart from background particles removed, image resize and white balance correction on background to correct for slight oxidation of balsam mount. Very little tonal balance correction is required as the scanner has a high dynamic range.

'Trichocera

hiemalis Winter gnat'

(Size - body length 16.4 mm)

This

slide shows the expert way the delicate long legs and antenna have been neatly

arranged. Its common name 'winter gnat' is apparently still in use as its

commonly seen in winter months although it is not a gnat but a crane fly in

the family Trichoceridae.

Links:

Excellent images of live insect on

Pavel Krásenký's 'Macrophotography

of insects' website.

'Winter

crane fly - Trichocera species' (in Dr David Larson's 'Insect of month'

series). A fascinating discussion on how this insect's physiology may be suited

for activity in winter months.

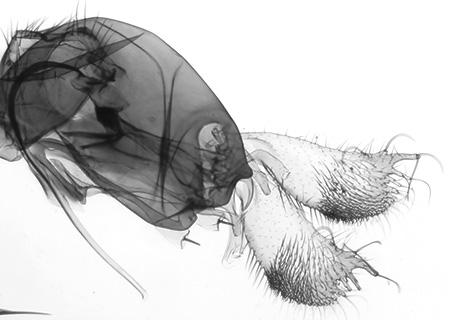

'Laccophilus

minutus Water

beetle'

(Size 11.2 x 7 mm as arranged)

Click here for master scan (1.5 Mbytes)

As

a pond dipping enthusiast, this water beetle is probably my favourite of the

six slides I possess by this mounter, although being more robust than the more

delicate insects it was probably easier to lay out. The scanner has retained

the attractive golden brown tint which the slide has acquired over the years.

The back legs have a fascinating variety of spines and hairs. This species is

illustrated in Chinery's invaluable insect guide (ref. 1) and is in the

Family Dytiscidae which includes the more familiar members such as the

great diving beetle Dytiscus marginalis. On-line species checklists indicate

that the species occurs in the UK.

Links:

Images of beetle on the Zoological

Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences website.

|

Slide scanner compared with digital SLR: I also imaged the above beetle with my Nikon D50 6 megapixel DSLR. To fill the frame I had to put 56 mm of extension tubes onto a Nikkor 60/2.8 macro lens. Not surprisingly the slide scanner easily out resolves the DSLR. Even assuming with the D50 that lack of camera shake (there's no mirror lock), a slight focus error or diffraction was not contributing which they could well be, a 5400 dpi scanner is theoretically resolving ca. 213 'dots per mm' if subject fills scan frame cf a 6 megapixel camera sensor with Bayer filter which gives ca. 60. The DSLR gives a competent resized image for a web page, but a single exposure from a camera tries to register the white backlight to grey which can't be fully compensated by overexposing or post capture tonal balance adjustment. A scanner is not taking a single exposure so with its high dynamic range it gives much brighter punchy looking images. Slide scanner compared with a compound microscope: In an earlier article the practical resolution of the 5400 dpi scanner was estimated to be ca. 7-10 microns by scanning a micrometer slide. This assumes the subject fills the scan area but is often much less; in this case the water beetle is only filling ca. a third of the 36 mm wide scanning field. The scanner's resolution is no match for even the humblest low power achromatic microscope objective (e.g. a 3.5x NA0.10 objective has a theoretical resolution of ca. 3 microns). So the microscope will be the imaging route of choice when fine detail needs to be studied or photographed as shown right. |

Left

above:

Nikon D50 DSLR, crop of RAW image with insect filling frame.

|

'Seven

spotted ladybird Coccinella 7 punctata'

(Size - 23.2 x 12.2 mm as arranged, including wings)

The

seven spotted ladybird is a very familiar insect in the UK. The mounter has

done well to flatten the globular beetle including the wing cases and laying

out the wings. The slide demonstrates the importance of not relying on just

a prepared subject to learn about an unfamiliar insect. Three dimensional information

is lost as well as colour, especially in old slides and the ladybird is

not immediately recognisable as the bright red beetle familiar to us.

Anne

Bruce wrote a fascinating illustrated article

on this species, how it is threatened by a parasitic wasp and the potential

impact that can have on the ladybird's role in agriculture.

|

Near infra red cf visible light: Regular readers may recall that I'm a fan of near infra-red imaging of insect mounts. The ladybird above with dense exoskeleton is more transmissive to near IR thus revealing detail which visible light struggles with. |

Detail

of right hand rear leg. |

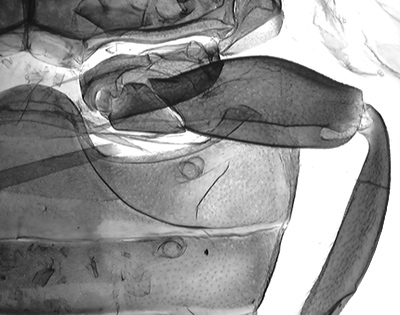

'Micropeza corrigiolata'

(Size

- body length 7mm)

This

species is illustrated in Chinery (1), apparently common and described as

a 'stilt-legged-fly' in the family Micropezidae. The legs are particularly

skilfully arranged in this mount. The head (as in some other slides shown

here) seems to have been arranged to show the mouthparts and appendages

more clearly.

Image

right, near IR image taken under LOMO compound microscope to show body detail.

Image presented as a digital negative.

Image

right, near IR image taken under LOMO compound microscope to show body detail.

Image presented as a digital negative.

Links:

Attractive image of

the live insect on the 'La

galerie de photos du monde des insectes' web site.

'Chironomus Plumed gnat'

(Size

- body length with antennae 21mm)

The species was not mentioned on the

slide and 'plumed gnats' seems to be one of the common names for members

of the parent Family Chironimidae. The family will be a familiar one to

the pond dipper as it includes the larvae known as bloodworms.

Links:

First

Nature's web page illustrating the larvae, pupae and adult of a typical

species, Chironomus plumosus.

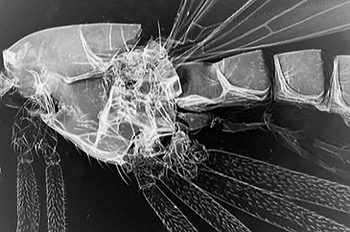

'Dolichopus aeneus'

(Size

- body length 9mm)

A Google search suggests that it is also known as Dolichopus ungulatus and in the family Dolichopodidae. The parent family common names include 'long legged flies'. The males are apparently noted for their large genitalia which may be the structures shown in the above image. There is also a common name on the slide by the mounter which I can't fully make out, it looks like 'Bra?y fantail'.

Detail

of genitalia. LOMO microscope and 9x planachro objective.

The dense exoskeleton again responds well to transmitted near IR lighting under a compound microscope. The image above is presented as a digital negative after tonal balance emphasis as the near IR originals tend to be very flat.

One

of the advantages of digital imaging is the ease at which slight imperfections

can be corrected for aesthetic image uses. The insect as mounted had

a broken leg (shown right) so was taken to the 'digital insect hospital' (Adobe

Photoshop Elements!) to repair it. The clean background readily

permits using one of the 'select part of image' tools and moving it to the more

likely correct position (as above).

One

of the advantages of digital imaging is the ease at which slight imperfections

can be corrected for aesthetic image uses. The insect as mounted had

a broken leg (shown right) so was taken to the 'digital insect hospital' (Adobe

Photoshop Elements!) to repair it. The clean background readily

permits using one of the 'select part of image' tools and moving it to the more

likely correct position (as above).

Links:

'Long-legged

flies' on the Canadian Biodiversity website.

Comments to the

author

David

Walker

are welcomed.

All images

by the author.

References

1)

Collins

Guide to the Insects of Britain and Western Europe by Michael Chinery. 1986.

Acknowledgements: With thanks to the many insect enthusiasts and entomologists who share their knowledge and photography on the web (including the authors of websites linked to above) to provide a valuable resource. Thanks also to Brian, the original seller of the slides, who provided a valuable insight on the mounts and currently unknown mounter.

Published in the March 2006 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is

at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk

with full mirror

at www.microscopy-uk.net

.