|

Get The LED Out by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Recently, I have been reading about the virtues and many applications of LED lights and so a few months ago, I came across a compact little unit with a single, blue lamp mounted at the end of a 5 ½ inch flexible cable which allows for a variety of positioning options and it was less than 10 dollars. I know that some of the blue LEDs emit ultraviolet light and thus should be used with caution. I’m not sure about this one, but as a general rule, I avoid looking at bright lights and sitting on hot stoves. The images I’m going to share with you here were taken with my Olympus stereo-zoom and I held the light rather than putting it in a clamp or holder–which I am almost sure, I will try next time–and I look at the image only on the mini-screen of my digital camera, so I think it unlikely that I incurred much risk.

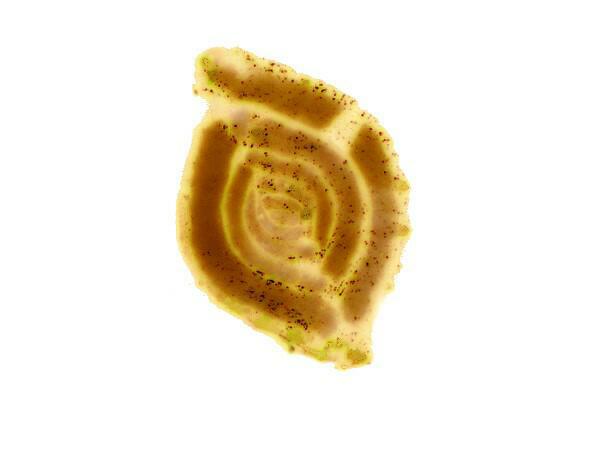

Some of the blue images turned out quite nicely; some struck me as pleasing, but others as rather artificial, and with some it doesn’t do at all what I want, because once I get the blue image, I want to transform it using the INVERT function in my graphics software. Why on Earth or Mars or Venus (well, we can understand about Venus) would I want to do that? As it turns out, the image reversal, in some instances, produces a very interesting effect, a sort of pseudo-Xray image. This is not just my imagination nor have I been imbibing too much Lagavulin (unfortunately).

Not too long ago, I was browsing through a beach sample from Malta which the wonderfully generous and splendid microscopist, Brian Darnton, sent to me several years ago. In re-examining it, I found some splendid specimens of forams, bryozoans, and tiny gastropod shells and since he is known especially for his distinguished work on forams, let’s begin with a specimen of one of those. This is a probably a specimen of Quniqueloculina. The taxonomy of foraminifera is a nightmare and is revised and updated almost constantly, so my interest here is in the imaging rather than the taxonomy.

This was photographed using brightfield, specifically a halogen fiber optic illuminator with an Olympus SZ III stereo-dissecting microscope.

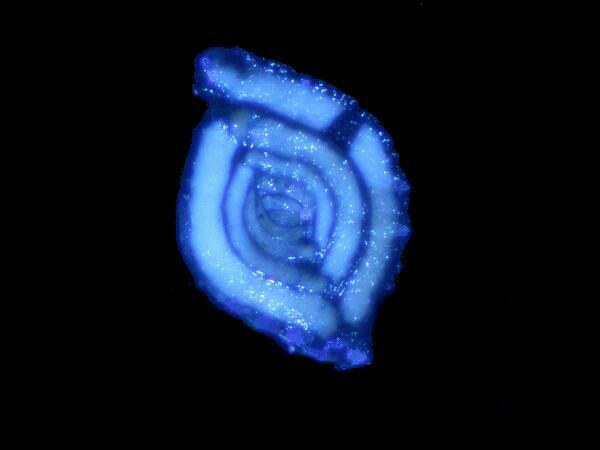

This is the same shell illuminated with the single blue LED.

As you can see, the contrast is somewhat different and some detail is rather better defined both along the edges and in the center. Nonetheless, I must admit that I find the intense blue color somewhat distracting and that is what prompted me to try out the INVERT function in the graphics program with the following result.

Here, there is, to my eye, the sense of looking into and through the shell in a manner rather different than that in the 2 previous images. The difference in background color may to a degree contribute to that.

I decided to try another foram and this time paint in a black background for the brightfield and the LED images; that meant, of course, that the application of the INVERT function would create a white background in the third image. So, here’s the brightfield image.

Here is the LED image.

Again some interesting and subtle differences, but still very blue. And then the INVERT image.

Now, “let me make one thing perfectly clear” as a former president used to say: The INVERT image is of the LED image, NOT of the brightfield image. This third image does, I think, present a rather different perspective than the other 2 and I find it both pleasing and informative.

The thought has occurred to me–and let me emphasize that I am not anti-blue– to cut some plastic filters of different colors to use as filters with the LED. I suspect that the results will be only marginally interesting but, nonetheless, I feel it’s worth a try. (As it turned out, it wasn’t.)

In this sample, I also found some nice specimens of the small tubeworm Spirorbis. There are many different modes of construction that tubeworms use and this one produces a predominately calcareous, spiral shell which is flattened on the bottom side. It must produce some kind of very effective adhesive for these are not easy to pry loose from a substrate without damaging them. I’m going to show you 3 images of the underside and 1 of the top side to give you an idea of this intriguing house for a little worm that extends its tentacles out of the end of the spiral in order to feed.

This is the top view using brightfield.

As it turned out the underside produced more interesting views using the LED and INVERT modes.

The same view using LED illumination.

And then the LED view modified with the INVERT function.

The differences in detail are not dramatic, but are significant enough to make a comparison of the 3 images interesting.

Clearly much depends upon the structure of the specimen and also the way in which the image was captured. Here is a photograph of a small snail which is “stacked” consisting of 20 images using the program Helicon Focus. This is an image which I quite like; however, when I apply the INVERT function to it, there is not only no improvement, but a degradation of the image.

This is the compiled or “stacked” image.

This is the INVERT image which, as you can clearly see, is inferior.

Much depends not only on the specimen, but on how both the brightfield and the LED images are processed after the application of the INVERT function.

This afternoon, I tried processing photographs of the madreporite of a small starfish, the surface of a coral-like sponge, a cluster of spicules from a glass sponge, the surface of a stalked sponge, and a plate from an echinoid, but none of them produced satisfactory images.

My best results thus far have come from forams, bryozoa, and small snails all of which are “chambered”. So, in the next few days, I plan to try out 2 other experiments: 1) to continue to search for suitable types of specimens including radiolaria and 2) to try out a little technique which I discovered some years ago (back in the 14th Century, I think) which involved using oil (immersion, mineral, or castor) with forams to enhance contrast in such a way as to make the chambers more readily visible. I hope to be able to include some of those results in this essay but, in the meantime, I want to look at 3 other specimens which have produced some interesting results.

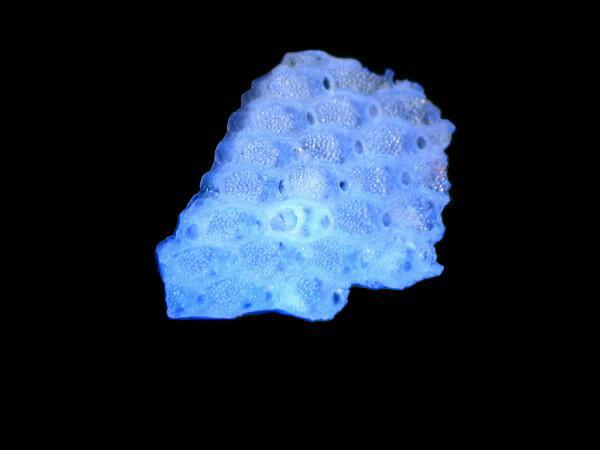

The first is a fragment of a bryozoan colony.

From this brightfield view, you can clearly see the “chambered” nature of the specimen; when alive each compartment contains a tiny animal with ciliated tentacles which it can extend from its minute refuge in order to feed.

Here, obviously, is the blue LED image and the compartments are still clearly visible but, perhaps not as distinctive as in the brightfield image. It is a peculiar and mysterious thing about human vision that, although we are strongly attracted to vivid, dramatic color differences, we, nonetheless sometimes can discover more detail from monochromatic images. Many photographers have used black and white images to create an emotional impact that would be diminished by color . With microscopes, a green filter is often used with phase images to help us notice subtleties that we might otherwise miss.

Now, let’s consider images of 2 little snails; the first is a rather ordinary looking little beastie, certainly not a candidate for the Escargot Institute and this is because this is not really a snail, but a sneaky little foram masquerading as a snail. It is a species of Cornuspira.

And then, of course the Cordon Blue LED image.

And the INVERT:

To my weak old eyes, this image suggests some detail not visible in the other 2 images. The issue then becomes whether or not this involves some significant, new information or whether it is simply irrelevant “noise.”

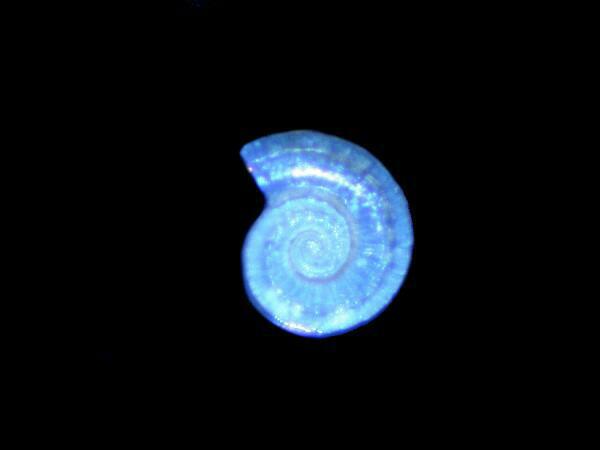

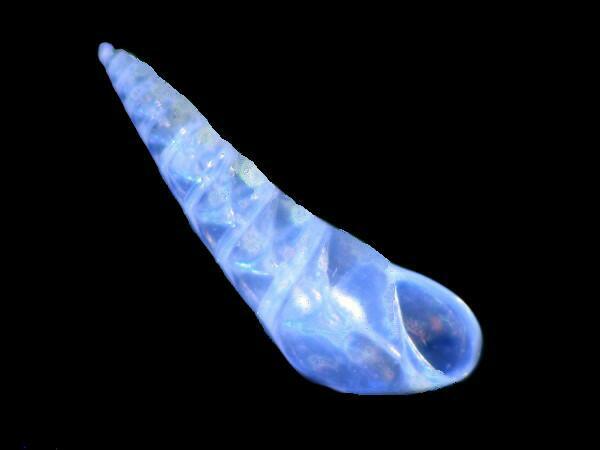

The next example, this time of a genuine small gastropod, presents that issue, in my view, even more strikingly. This is a lovely little specimen.

One of the things that makes this such a good candidate for this experiment is its translucence.

To my mind, this is probably the best LED image which I have captured thus far and it seems almost luminescent.

This image I find rather striking and out of the LED INVERT images, it suggests to me most a similarity to an X-ray (or if you think that’s too strong a claim, perhaps a Y-ray). These 3 images in concert do, I think, underscore how different contrast and processing techniques can lead us to see detail in an object which we might otherwise have missed.

I did, as promised, try out some additional types of specimens but, so far, I am not yet pleased with the results. However, rest assured that if Ido find some I like, I will write yet another article which you can ignore–ain’t Internet freedom wonderful?

I also did try out a series of different sorts of oils on forams and with enough success to prompt me to deal with this subject in a separate essay which will be coming soon to a local theater near you.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .