|

Magnificent Silence: Some Reflections by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

To borrow from Simon and Garfunkel, I fear for the loss of the sound of silence. The population of our poor, ravaged planet has exploded to about 6.7 billion people and that’s probably a conservative number. Accurate census-taking in the jungles of Borneo, the Amazon Basin, remote areas of China and India, and scattered Pacific Islands is a difficult, in fact, almost impossible task. Even in the United States, The Census Bureau has to rely on questionnaires and then juggle the figures to try to account for those who seek isolation and those who are homeless. The reason that population matters is that people are very noisy and many have pets and livestock that are noisy. However, the industrial and now the technological revolution have escalated the amount of noise exponentially. If Mars were inhabited by sentient, intelligent beings, I’m sure that by now we would have received a message saying: “Hey, keep the racket down over there!”

When I wander up into alpine meadows bursting with wildflowers or climb down to a string of spring-fed beaver ponds or walk along the edge of a lake where the only sounds are the lapping of the waves, the sound of ducks, geese, pelicans, and blue herons accompanied by the occasional splash of a leaping fish, I experience a sense of inner peace and calm joy that is indescribable and of transcendental importance to me. To sit at the edge of a pond and watch dragon flies and damsel flies darting and weaving through the still air is glorious and in the background there is the soft hum of the activity of life–bees, beetles, small birds, all carrying out their routines essential to survival. Such events provide me with a sense of connectedness to a small part of nature and I am reminded of the vastness of the universe in which we live ever so briefly.

The ancient Greeks developed a wonderfully rich concept designated by the word thauma which means awe, wonder, astonishment, amazement–an incredible accomplishment what with their wine-driven symposia and their orgies–Puritans they weren’t with the exception of a few Attic ultraconservatives, such as, Lush Limbopolous. These early thinkers were surrounded by phenomena which they didn’t understand and yet they were no longer willing simply to accept the mythological explanations which their culture had created and nourished. They had none of our science and technology which explains so much while at the same time revealing new mysteries and puzzles for us to investigate. This ancient sense of astonishment arose out of the immediacy of the simple act of looking up into the sky on a clear night and experiencing a complex mixture of awe, grandeur, and overwhelming insignificance which should move any thinking being to silence and contemplation. Now, in many areas of the world, the air is so polluted that seeing the stars has become a rare event. Years ago, when my wife and I were graduate students in Los Angeles, the smog was so bad that I used to joke that we would wake up in the morning and hear the birds coughing.

Now we know about blue giants, white dwarfs, nebulae, galaxies, black holes, about the atmospheres of Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter and yet we know almost nothing–just look at the images from the Hubble telescope and if they don’t amaze and humble you, then nothing will.

As Einstein remarked: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.” And, in the vastness of empty space, there are these unimaginably immense cathedrals of silence. I find this very comforting while admitting that there may be other kinds of intelligent beings who experience that silence as a cosmic symphony.

As social organisms which live in increasingly dense proximity to one another, we confront a paradoxical conflict; on the one hand, an increased need to be in almost constant communication and, on the other, a need for isolation. In an almost perversely ironic way, we have used technology to provide us with a set of solutions. You can now own a handheld device that is a telephone, a camera, a miniature computer, a music library and a means of accessing the Internet–you never need feel lonely again and you also have the illusion of control and power, for you can avoid real contact with other people; you can ostracize them by ignoring their calls or e-mails or even block their access to your system if they do something to annoy you. By putting a profile on Facebook or MySpace, you can have hundreds, even thousands of “friends”; you can create a blog and share your most intimate feelings, thoughts, and even photographs, and, by means of Twitter–a sort of public/private diary–, you can provide constant brief updates of everything that you are doing. Frankly, I find such an egocentric compulsion to communicate, to “be in touch” both desperate and pathetic, in part because it has become a deep-seated psychological addiction for many.

One of the most profound aspects of deep friendship is the ability of two people to sit quietly and share silence, to not feel the need to say something interesting or witty or simply make idle chatter to fill up the silence. There is a wonderful story, perhaps apocryphal, but I prefer to believe that it is true. It concerns two well-known writers who would meet one evening a week to have a drink or two, smoke their pipes, and talk. On one occasion, they sat for several hours with their drinks and pipes in front of the fireplace without exchanging a word. On departing, they both agreed that it had been one of the most pleasant evenings they had ever spent together. I regret that I no longer recall their names; what is left of my memory these days, I largely reserve for microscopy, natural history, and rants against contemporary stupidities. [I happened to mention this to a colleague of mine on the English Faculty and the story sounded familiar to him as well. So, I am indebted to Eric Nye for the some ingenious computer searches which came up with the following passage from a book called Tobacco Talk and Smokers’ Gossip published in London in 1885 which I will share with you here:

Emerson and Carlyle

“The friendship formed by these two men at Craigenputtock lasted during their lives. There is an unpublished legend to the effect that on one evening passed at Cragienputtock by Emerson in 1833, Carlyle gave him a pipe, and taking one himself, the two sat silent till midnight, and then parted, shaking hands, with congratulations on the profitable pleasant evening they had enjoyed.” (p. 43)]

We are creatures who have evolved in such a way that we often have conflicting desires, needs and abilities. We have succeeded in creating machines that are quite good at multi-tasking and we have tried to convince ourselves that we also are good at it but, in fact, our abilities in this regard remain quite limited when creative or contemplative mental activity is involved. If I were younger and more technologically savvy, I would invent a cellphone that would self-destruct when anyone tried to drive and text at the same time.

Apparently more and more people are insecure with silence or simply with the sounds of nature. I would always rather listening to a babbling brook than a babbling teenager. It is also depressing to encounter a hiker with an iPod striding along listening to rap “music”. Maybe, just maybe, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, the “Pastorale”–but, no, I would veto even that. The point of being out in nature is, in significant part, to escape the tethers of technology and revel in the sounds of nature (ruling out the buzzing of swarms of mosquitos and biting flies). Furthermore, those natural sounds can focus one’s attention on visual delights as well, the whirr of a hummingbird’s wings, the song of a lark, the busy buzzing of bees pollinating, can make one look at the surrounding landscape differently.

Such solitude is becoming rarer and rarer especially in populated areas and, of course, most especially in urban areas. However, even parks and wilderness areas are experiencing, more and more frequently, 4-wheel drive vehicles, All-Terrain-Vehicles, snowmobiles, RVs the size of Greyhound buses, and diesel pickup trucks that I swear have never been near a muffler. If you want a quietness tempered only by the sounds of nature, don’t go to Yellowstone nor any National Park, State park, nor anyplace where people can drag in the paraphernalia of the industrial and/or technological revolutions. I also think that anybody caught littering should be sentenced to a year of hard labor cleaning up parks and highway verges. I know, I know, I’m just a cranky old curmudgeon and few will take any of this seriously until the air becomes unbreathable, what potable water remains is scarce and expensive, and the exponential spiral of overpopulation radically intensifies the violence, disease, mismanagement, war, and corruption that are already well on their way to becoming hallmarks of modern life (or, I suppose, I should say postmodern life).

Any attempt to return to a Romantic idyll of natural simplicity, such as, Thoreau’s Walden Pond, is entirely futile. I think that it is imperative that children be provided the opportunity to learn about the wonderful complexities of nature for two fundamental reasons: 1) the sheer delight of discovery and 2) in the hope that they might have more sense than most adults in realizing that we MUST stop the destruction of our home, planet Earth.

Without the magnificent silence of nature, there can be no true contemplation and creative reverie and without those we are in danger of losing contact with crucial aspects of our own psyche that shape and direct our intelligence and creativity. These are not gifts which we are given at birth; our enormous brain capacity makes us highly dependent and vulnerable. Had I been born and raised in a coastal village in Bangladesh which was subject to yearly flooding, it is highly unlikely that I would ever have submitted a single essay to Micscape. In fact, I could well have ended up illiterate, malnourished, directing all of my energies to the task of simply surviving the ravages of nature–I told you I’m not a Romantic. This is all the more reason that we must use all of our abilities to try to live in harmony with nature to minimize our harm to it and its harm to us. To accomplish that we must educate children and that doesn’t mean just incarcerating them for 8 hours a day, 9 months a year in buildings designed by prison architects, but coming to grips with the fact that education begins in our first year of existence and should extend through to our last breath. Furthermore, it is an enterprise of community and not simply that of a public institution. The ancient Greeks had a powerfully intelligent conception which they called paideia. It meant that virtually every aspect of culture was a dimension of education–architecture, public discourse, sculpture, athletic contests, the agora or market place and, of course, the theater. Here over 2000 years ago, Greek tragedians gave citizens much to think about in terms of the nature of society, politics, the cosmos and their place in the mysteriousness of existing. The radical freedom granted to the ancient comic playwrights, such as Aristophanes, was unprecedented. Here was a playwright who poked fun at Socrates, at the tragedians, at the politicians, at the moral hypocrisy of the Athenians, and would even use the names of prominent citizens whom he thought had violated the good of the larger social fabric. He was perhaps the first defender of women’s rights in his outrageous, and hilariously brilliant and ribald play, Lysistrata. These same Greeks also tolerated that incisively sane “madman” Diogenes of Sinope, the Cynic. The Greek word for cynic means “dog”, which is a tad judgmental but nonetheless, he was tolerated and on the occasion when some youthful Athenian rowdys, the equivalent of British soccer fans, broke Diogenes’ “house”, the Athenians not only punished the rowdys, but took up a collection to buy him a new ‘house”. You see, his house was a large pottery vessel up on the Acropolis and the rowdy youths threw rocks at it and ruined it. Athenian citizens replaced his “house”. Many hated Diogenes, but prized freedom above all. He was a constant critic of the Athenians and their institutions, but an informed one, so this even was a radical exercise in democracy–demos=the people; democracy=rule by the people. Unfortunately, as newspapers, radio, television, and more recently blogs, texting, and tweets evolved, these means of communication have shown that radical technological democracy is a catastrophe, because an appalling percentage of the population is uninformed about the majority of significant issues that affect them and the survival of the human species. Nonetheless, a few ancient Greeks among them Gorgias, perhaps the most radical of the Sophists, was the most extreme relativistic subjectivist and stated that any individual’s opinion is as good as that of anyone else. This is, of course, sheer nonsense and, I think that perhaps even Gorgias might reconsider his notion in the age of the Internet. Part of education should focus on teaching the young that when they don’t have the relevant information and the critical abilities to analyze and evaluate the relevant data, then they should remain silent until they have learned how to do that very demanding work. Thus silence can also have important social, political, and cultural consequences.

While I don’t want Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, or Haydn with me when I’m out walking and collecting, my laboratory is, for me a least, another matter. As I observe certain organisms, there are pieces of music that seem particularly appropriate. If I had to chose between music and microscopy, I would be hard put; one is an auditory festival and the other a visual feast which is why I try to blend them as much as possible. In one corner of my lab, I have a stereo amplifier (to complement my stereo microscope, of course), a CD player and two 2½ foot high speaker cabinets. It’s not the system of a fanatic audiophile, but it produces very good sound. I have a substantial collection of CDs, predominately classical and a modest number of recordings of mellow jazz and folk music, some Beatles, and a bit of rock from the 60s and 70s. There are a number of types of noise which I refuse to recognize as music–hard rock, acid rock, alkali rock, champagne music, elevator music, country and western, rap, etc. and, in addition, I must admit that I have certain cultural biases I cannot abide Indian music, either American or Eastern–five minutes of Ravi Shankar is more than enough; I despise Mexican Salsa Music when you’re trying to eat enchiladas; Gypsy music when you’re savoring a spicy goulash, Arabian vocal music that involves ululation; Flamenco, German beer hall music, Japanese koto music–in other words, when it comes to music, I am a terrible snob and have a very narrow range of tastes. There is even a fair amount of Western Classical music that I either despise or find boring or ludicrous. For sheer giggles, you can’t surpass Albrechtsberger’s Concerti for Jews-Harp, Mandora, and Orchestra. Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory is a lumbering elephant; Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon is a grotesque monstrosity; Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto gives me a migraine; Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach should be titled Einstein on the Beach on the Beach on the Beach on the Beach, etc. He is the musical Gertrude Stein. Don’t misunderstand, there is a lot of experimental classical music and jazz that is truly interesting, adventurous, alluring, intellectually and aesthetically exciting and is yet still musical (e.g. Giya Kancheli and his use of silence) and which is not the anti-musical piffle of John Cage or Stockhausen. If this little outburst has offended your sensibilities, please spare me outraged e-mails; I’m 71 years old and thus bloody unlikely to change my tastes and I don’t trust anyone under 70 and regard those over 70 as potentially senile. If you disagree with me, that’s alright, for as Nietzsche said: “All life is a matter of taste and tasting.” However, when it comes to music, Nietzsche was a dimwit too. He thought Carmen was the greatest opera composed up until that time–if I’m ever forced to liste to the Habanera one more time, I will scream. Furthermore, until Nietzsche wised up, he thought Wagner was a great composer. I detest Wagner’s politics, his racism, and his music. I used to upset some of my students when I told them that I thought Wagner was a 10th rate composer and I regard that assessment as generous.

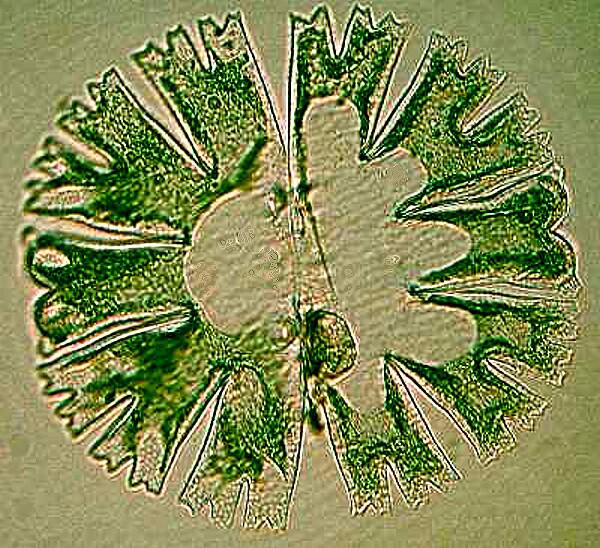

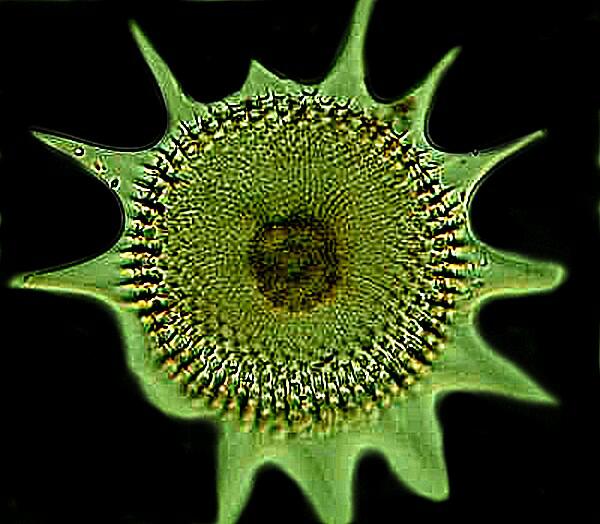

So, now that I’ve provided a framework, back to microscopy and music. When I’m looking at desmids, especially species of Micrasterias which have lovely convolutions and frills, I like to listen to Mozart whose music is also full of lovely frills.

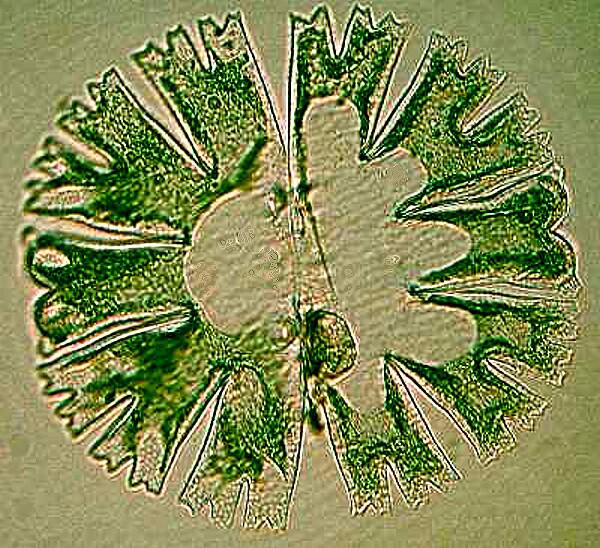

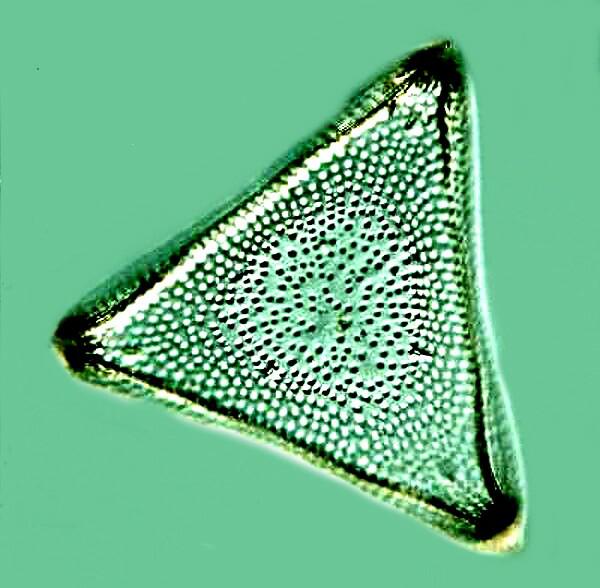

However, Mozart won’t do at all for diatoms; here one requires

the structural and mathematical precision of Bach.

I find the Partitas particularly appropriate, but Bach created such a rich, extensive body of work that the diatomist need never fear running out of good listening. Of course, the same is true of the desmidiologist and the enormous output of Mozart or “Wolfie” as his wife called him.

One can get even more specific and associate a particular piece of music with a particular species of organism. For example, when watching a large species of Spirostomum, Johann Strauss Jr.’s Blue Danube Waltz is a nice accompaniment to the slow, gliding elegance of the organism as it floats through the water.

It also works well for Volvox. Look up Wim van Egmond’s splendid article on Volvox which you can find here:

Of course, a trumpet concerto or even a nice trumpet voluntary is an ideal accompaniment to viewing Stentor.

The mildly whimsical Trois Gymnopedie of Erik Satie are a nice fit for the lovely transparent vase-like rotifer Asplanchna with its glides and pauses. If you’re not familiar with Satie, do explore his music. He composed mostly for piano and had an irrepressible sense of humor. He would write “instructions” above certain passages of his music, such as, “Open the head!” or “To be played like a nightingale with a toothache.”

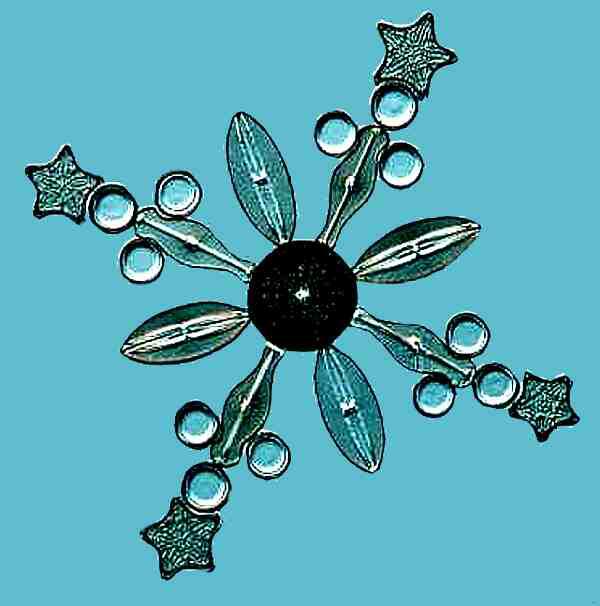

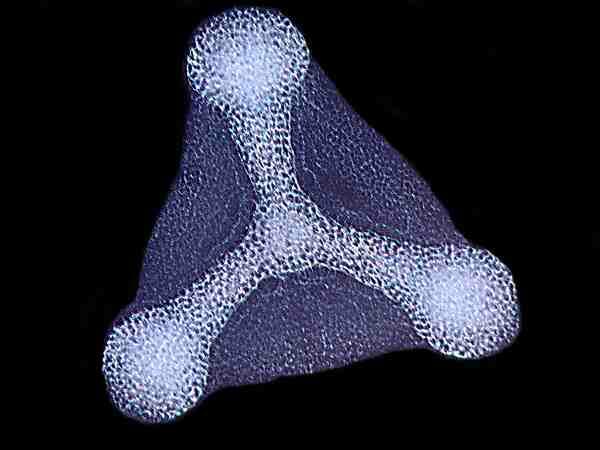

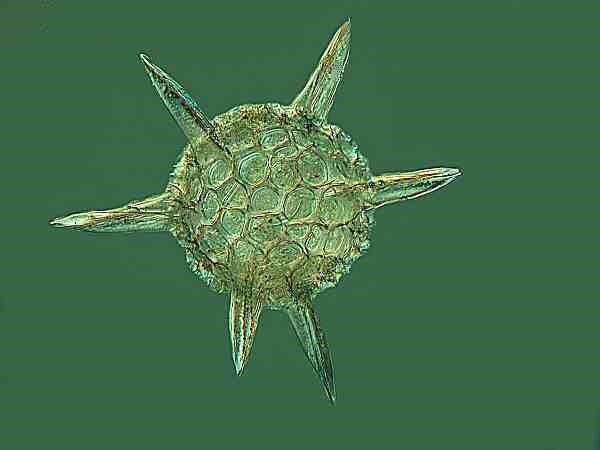

Radiolaria are common numberwise, but are uncommonly beautiful and the same may be said for Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man” from his Third Symphony. Radiolaria float into view and display themselves gloriously just as the Fanfare opens and expands like a musical flower.

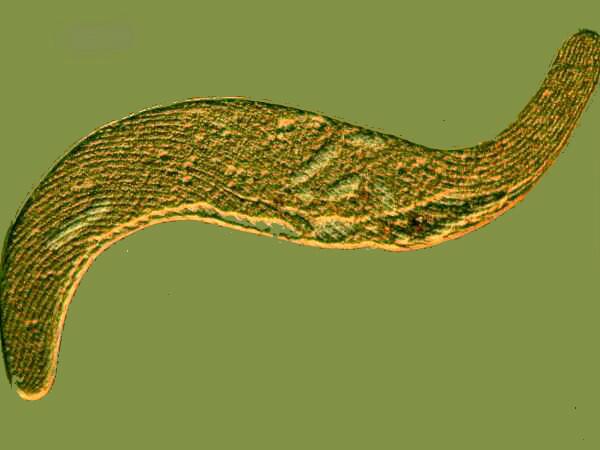

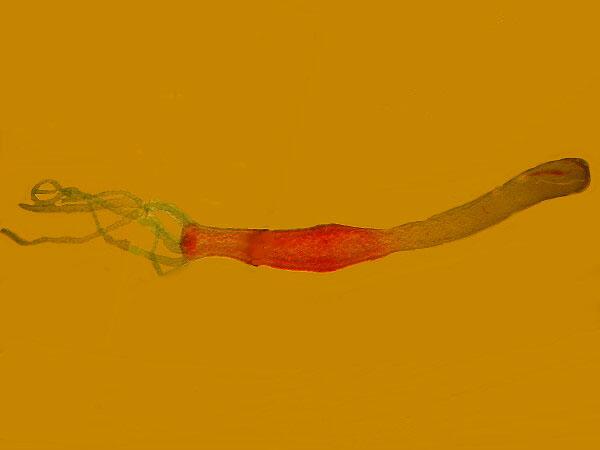

Aquatic nematodes, which are small “worms”, seem to be in a constant restless state of undulation. Visually they remind me of the of the period of Soviet “socialist realist” art. In the Tretyakov art gallery in Moscow, above the landing of a wide staircase was a gigantic painting of Lenin addressing the masses, his arm outstretched in the familiar pose of a fanatical autocrat. There were paintings of laborers and their tractors, some even done in large stained glass windows in the Agricultural and Engineering Exhibition–in other words, a celebration and glorification of Soviet industrialism (not all that unlike some of the W.P.A. projects of the 1930s and 1940s in the United States). In the Soviet Union, there were composers who wrote pieces of “industrial” music which were meant to embody the mechanical sounds and rhythms of factories. Nematodes never tire, hour after hour repeating the same boring twists and turns in a manner most mechanical (to paraphrase Gilbert & Sullivan). So, if you can stand it, Soviet industrial music is the ideal accompaniment to viewing nematodes.

I was thinking just now about Bursaria truncatella and its great, grand gliding motion and thought that the Great Gate of Kiev from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Pictures at an Exhibition would be a fitting companion–majestic and imperial.

Halteria grandinella, that leaping, twitchy little hypotrich would, I think, be well served by some gymnastic ballet music–your choice. Coleps, those odd little armor-plated barrels which whirl and attack, relentlessly feeding like jackals on Paramecia, I can readily associate with Khatchaturian’s Gayne Ballet Suite.

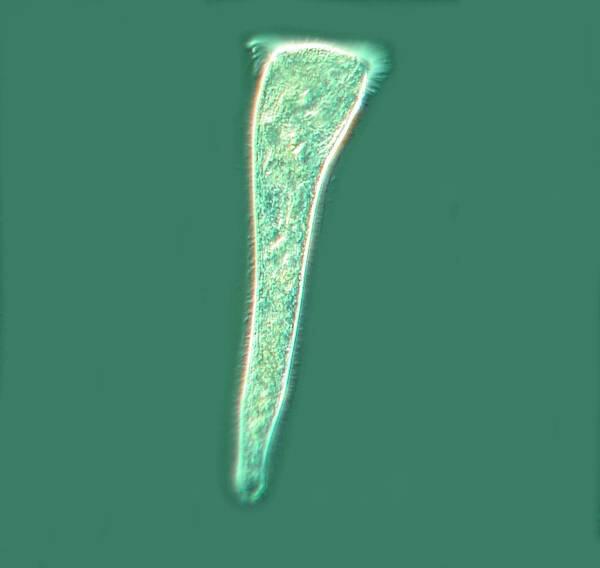

Phacus, a wonderful relative of Euglena, is constructed like a multi-dimensional leaf which rotates and twists as it moves through the water and some of the slower waltzes of Chopin are an excellent accompaniment. This marvelous creature does indeed appear to be dancing to its own aquatic-cosmic music.

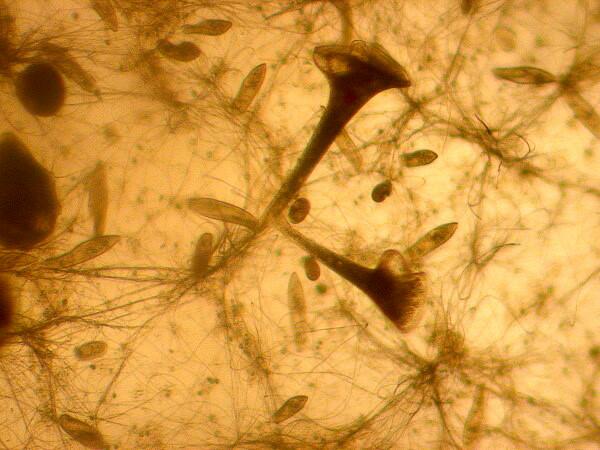

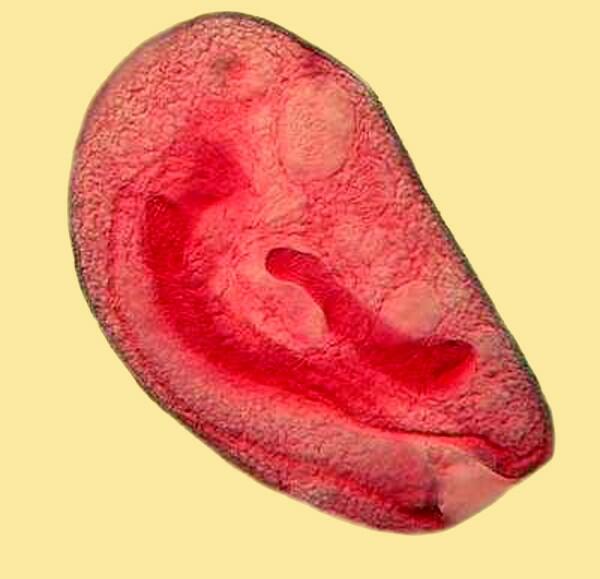

Virtually every amateur microscopist is familiar with either the freshwater Hydra or marine hydroids or both.

They expand, extending their tentacles and wait, the tentacles floating in the currents like delicate threads which are armed with deadly nematocysts or “stinging cells”. They seem endlessly patient and passive until a potential prey happens to brush against a tentacle and then it’s like the cannons going off in Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

I realize that all of this is a bit fanciful and highly subjective, but quite fun nonetheless. I would be delighted to know if there are other weird souls out there that associate particular composers or compositions with specific organisms.

One final note is that the death of an organism or a whole culture brings me back to the stunningly powerful opening of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, that section entitled “O Fortuna”, a reminder that we are all ultimately subject to the dictates of Fate.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .