John Nokes Furze, 1817 - 1859

by Brian Stevenson, Kentucky, USA

John N. Furze was an early member of the Microscopical Society of London (later the Royal Microscopical Society). He is best known to modern-day slide collectors for having placed distinctive green oval labels on the slides he owned (Figure 1). These labels bear Furze’s lithographed name, plus handwritten specimen description and date of acquisition. Slides from Furze’s collection tend to have been made by high-quality professional slide-makers or by well-known microscopists who gave/traded slides with Furze.

Figure 1. Four microscope slides from John Furze’s collection. Left to right: a deep, fluid mount of stained & corroded rabbit lung by professional slide-maker Alexander Hett (dated April, 1854); a shallow, fluid mount of corroded human lung tissue, also by Hett (dated January, 1857); a balsam mount of urinary calculi, from Dr. Lionel Smith Beale, author of several books on microscopy and medicine (dated April, 1853); and a balsam mount of a blowfly spiracle, by professional slide-maker John T. Norman (dated March, 1855). Furze’s labels covered over the descriptions that Hett etched into the glass of his slides.

John Nokes Furze was born November 18, 1817, son of John and Frances Furze. He was christened on December 12 of that year, in the parish church of St Dunstan in the West. At the time of son John’s birth, his father worked as a cordwainer. By the time younger brother William was born in 1820, the father had taken up boot making as his occupation. The 1823 Kent’s Original London Directory recorded John Furze as a boot maker, located at 65 Fleet Street. As an aside, today the rear of this building at 65 Fleet Street has been excavated to reveal a medieval crypt left from the monastery of Whitefriars. It is displayed to the public, and can be seen on the internet at the URL listed in the Resources section of this essay.

John N. Furze matriculated at Queen’s College, Oxford on May 21, 1836, at the age of 18. Oxford records report his father to have been a “gentleman”. Examination of 19th century English records show that it was fairly common for working-class men hid their low rank by claiming to be gentlemen of leisure.

By the summer of 1841, Furze was working as a brewer, and living in Newcastle Street, St. Mary Whitechapel, London. On November 7, 1843, Furze read a paper entitled “Observations on fermentation” to the Chemical Society. It was later printed in several publications, including the Philosophical Magazine. Furze first described his invention of an enclosed fermentation vessel, fitted with hoses to allow escape of fermentation gasses, and a water trap at the ends of the hoses to exclude air from entering the fermenter: “In consequence of the practical inconveniences arising to brewers from want of control over the fermenting tuns, and the changes in the worts dependent upon atmospheric temperature, I was led to the following experimental observations. The infusion of malt being made according to the usual practice of brewing, the wort, or infusion, is boiled with the hops, and being subsequently cooled, yeast to the amount of about one pound by weight to the barrel of wort is added, and the whole transferred to the fermenting tun, The general form of a brewer's fermenting tun being that of a simple open vessel, the worts lie exposed during their change of state without covering and with free access of air. This, as is evident, must expose the fermenting mass to the variations of atmospheric temperature, which, in their turn, either check or hasten the operation to such an extent, that the ultimate success of the brewing is endangered, and not unfrequently considerable loss is sustained. These disadvantages are occasionally avoided in some of the larger breweries by the use of fermenting tuns, which are so far inclosed as to leave but sufficient space for the escape of the gaseous matters arising from the surface of the worts when the fermentation is in full vigour. Having tried the above method without finding the desired advantage to result from it, new measures of proceeding were taken, as follows: A circular tun was erected, whose total content was 350 barrels, having a door in the side capable of being made air-tight by lining its edges with coarse serge and applying screw-pressure to the centre of it. To the upper part of this tun, which was fitted with windows in the top and sides to afford to the brewer an opportunity of viewing the apparent changes in the worts, two India-rubber pipes were attached, each of 1 inch internal diameter, to convey away the gas generated during the process; and, in order to prevent external interference, the ends of the pipes were immersed to the depth of about 3 inches in a vessel of water”.

It is notable that Furze thought that exposure to air led to spoilage because of the air’s temperature. I find it curious that Furze thought air temperature would effect the internal temperature of an enclosed vessel differently than it would an open vessel. Clearly, he was grasping at straws to explain his observation based on the knowledge of his time. It would be more than 10 years before Louis Pasteur demonstrated that spoilage was due to contamination with other microbes, which could easily get into the fermenting wort exposed to the air.

Furze also observed that significant quantities of alcohol would end up in his water traps. While the amount of alcohol was not sufficient to make it economically feasible to distill for sale, it was clear that a substantial amount of the brewer’s desired product was being lost. After much experimenting, Furze discovered that by immersing the ends of the gas escape hoses to a depth of 3 feet was sufficient to reduce the amount of lost alcohol, but did not create too much back pressure to rupture the tank’s seals.

Furze’s report ended with the note, “I have much pleasure in acknowledging the material assistance afforded me by my friend Mr. Robert Warington in these investigations”. Warington was a chemist and a fellow member of the Microscopical Society. In his Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Brian Bracegirdle pointed out that Furze had labeled a microphotograph slide of his friend as “Warington”, although Society records generally spelled the gentleman’s name with two “r”s (i.e. Warrington). However, writings by Robert Warington spelled his name with only one “r” (see the Resources section for some examples). It appears that his friend Furze got the spelling correct, but the Microscopical Society secretaries or printers frequently misspelled it (see Figure 2).

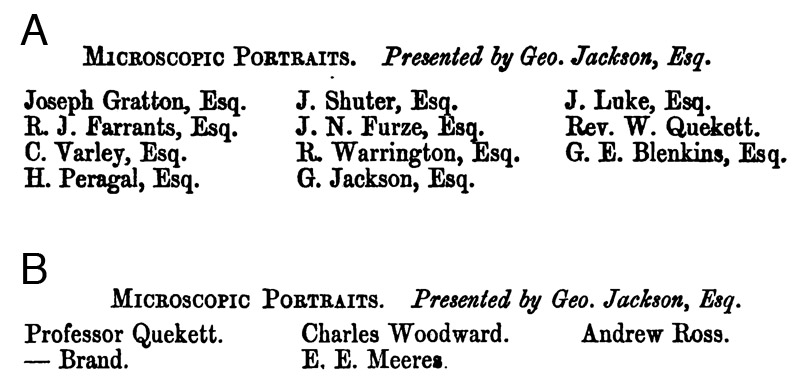

Figure 2. Microscope slides of microscopical photographs donated by George Jackson to the Royal Microscopical Society in (A) 1859 and (B) 1860. These included a microphotograph of John Furze. Brian Bracegirdle’s Microscopical Mounts and Mounters illustrates 3 of these slides, of Warington, Quekett and Ross. Dr. Bracegirdle suggested that the slide of Warington, which has only Furze’s green labels attached, was made by Jackson. This information, from the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, indicates that it was, indeed, made by Jackson. Note that the journal misspelled Warington’s name. The Furze-labeled slide shown by Bracegirdle is dated 1856, indicating that Jackson made several copies of these microphotograph slides.

On October 17, 1844, John married Mary Hodgson at the Islington parish church. They had 8 children over the next 15 years.

Furze named his Whitechapel operation “The Model Brewery”, which appears to have later been re-named “The St. George Brewery”. Records suggest he may have operated additional breweries in the London area. By the early 1850s, he was a member of Board of Directors of the Kent Mutual Fire Insurance Co., suggesting that he had substantial financial and/or political connections.

John Furze was elected to serve on the Council of the Royal Microscopical Society in 1855. He served for two years, then stepped down, according to Society rules. He also served as Society auditor in 1859, and possibly during other years.

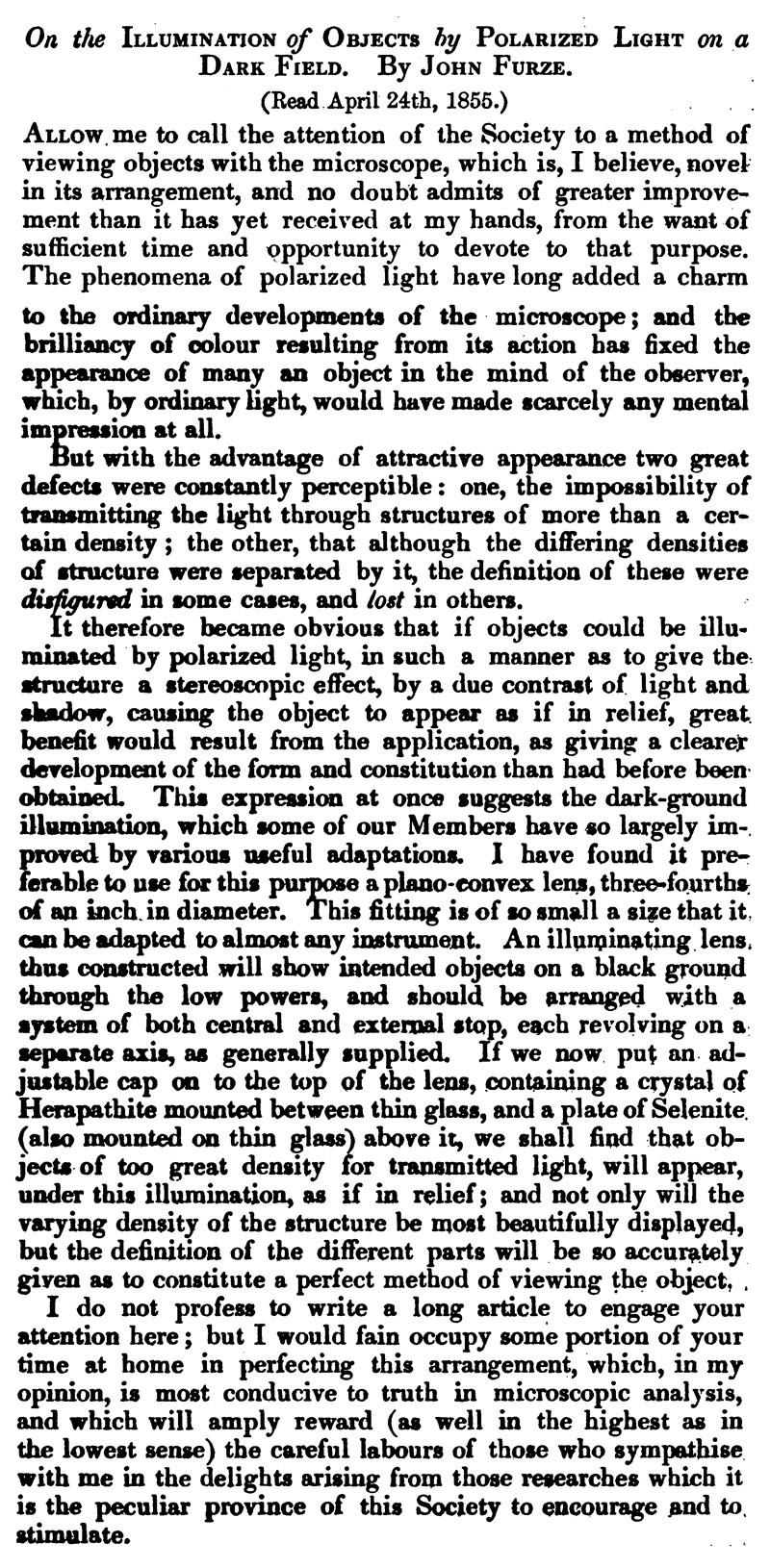

On April 24, 1855, Furze presented a talk on dark field illumination using polarized light (Figure 3). Several other notes from the Society mention Furze exhibiting specimens using this method, suggesting that it was a particular fascination of his.

Figure 3. Furze’s report on the use of polarized light with dark field. Reprinted from the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, 1855, Volume 3.

John Nokes Furze died at his home at 23 Leicester Gardens, Hyde Park, during the summer of 1859. He was buried July 20. He was only 41 years old when he died. His wife, Mary, lived until 1910.

In his 1860 Royal Microscopical Society President’s Address, Edwin Lankester stated, “The death of Mr. Furze is one that must have caused great pain and surprise to many of the members. He was a man in the prime of life, and carrying on a large and successful business; but in the midst of all he found time to cultivate a taste for microscopic research. Without contributing to our Transactions, he took a great interest in our proceedings; and the intelligence and energy with which he cultivated the microscope, as an instrument of research, must have done much to recommend its use amongst a large circle of his friends and acquaintance. I accidentally had a proof of this some years ago, when visiting a village by the sea-side, in the county of Suffolk, where I found Mr. Furze had been staying for a few weeks before I had arrived. I had not long been there before I heard of the impression he had produced on the minds of the villagers by his daily demonstrations, upon the sea-shore, of the microscopic structure of the creatures with which the coast abounded. I have often thought that this would form the subject for a picture to a painter of the nineteenth century - a naturalist exhibiting the wonders of animal structure through a microscope to a rural population. By such pictures the great history of our civilization might be told”.

Comments to the author will be welcomed.

Author’s note

I would greatly appreciate any information on the whereabouts of microphotographs of John Furze that were made by George Jackson in 1859. Other photographs of Furze would also be appreciated.

This and other biographies of historical microscopists are also available at http://microscopist.net

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Howard Lynk for providing images and for many constructive discussions on historical microscopy.

Resources

Alumni Oxonienses: the members of the University of Oxford, 1715 - 1886, Volume 2 (1888) Entry for John Nokes Furze, page 501

Bracegirdle, Brian (1998) Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, Quekett Microscopical Club, London

Burial record of John Noble (sic) Furze (1859) All Souls Cemetery

Catalogue of the Library of the Late J. N. Furze, esq. … (1862) Sotheby and Wilkinson, London. Noted in Répertoire universel de bibliographie, by Léon Techener, 1869

Christening record of John Nokes Furze (1817) St Dunstan in the West Parish Church

Christening record of William Furze (1820) St Dunstan in the West Parish Church

Christening record of Henry Furze (1822) St Dunstan in the West Parish Church

Christening record of Frances Furze (1824) St Dunstan in the West Parish Church

The City 14 photo – Niall Counihan photos at pbase.com (undated web page) Modern photograph and description of the crypt at 65 Fleet Street, London, http://www.pbase.com/nico100/image/78383173

England census, birth, marriage and death records, accessed through ancestry.co.uk

Furze, John N. (1855) Observations on fermentation, Philosophical Magazine, Vol. 24, pages 372-374

Furze, John N. (1844) On the illumination of objects by polarized light on a dark field, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 3, pages 63-64

The Gentleman’s Magazine (1859) Obituary of John Nokes Furze, Vol. 207, page 202

Lankester, Edwin (1860) The President’s address, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 8, page 88

Kent’s Original London Directory (1823) Furze, John, page 129

National Archives (1859) Probate will of John Furze, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/A2A/records.aspx?cat=074-o64&cid=-1#-1

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1855) Report of the fifteenth annual meeting of the Microscopical Society, Vol. 3, page 65

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1857) Vol. 5, page 258

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1859) Auditor’s report, Vol. 7, page 63

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1859) Donations to the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 7, page 125

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1860) Donations to the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 8, page 110

Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science (1860) Annual Soiree of the Royal Microscopical Society, Vol. 8, page 263

The Register Insurance Directory (1854) page 75

Varall, Brian H. (undated web site) Varall x Newbatt, http://www.varrall.net/wc34/wc34_095.htm

Warington, Robert (1845) Note on a means of preserving the crystals of salts as permanent objects for microscopic investigation, Memoirs and Proceedings of the Chemical Society of London, Vol. 2, pages 71-72

Warington, Robert (1853) On preserving the balance between the animal and vegetable organisms in sea water, Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Vol. 11, pages 319-323

Warington, Robert (1858) On the aquarium, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 6, pages 67-73

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the November 2010 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .