|

Infrared Images Are Not Infradig by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

“Infradig” is one of those words that sounds like it came out of the Hippie days of 60s America. However, in fact, it is a shortened version of the Latin phrase, “infra dignitatem” which means “beneath one’s dignity” and in this form, it came from the distinguished critic, artist, and philosopher, William Hazlitt. The first occurrence of the shortened form “infradig” shows up in 1825 in a novel of Sir Walter Scott. The attitude incorporated by the term is ironically at odds with those who it might be imagined would use it. Imagine a wealthy matron chastising her daughter for having an interest in rap music. It would be infradig of her to use the term “infradig”. So, instead she might tell her daughter: “Penelope, your interest in that so-called music is infra dignitatem!” And one can imagine her rebellious daughter saying: “Are you for real? Like what are you saying?”

In any case, my point here is twofold: 1) I love the eccentricities of language and 2) infrared images are perfectly respectable in the microscopic community and I’ll try to demonstrate that to you.

For reasons that I no longer recall, some of my images turned out to have a distinct light-rose tint and others a light-blue tint. I’ll show you one of each here. The first is of a large tree in a neighbor’s yard and the second is the foot of a fly.

The only alteration I made in these 2 images was to reduce size for the Micscape format, otherwise they are untouched.

The next image is of a juniper bush along the stairs leading up to our front porch. It looks as though there is lots of snow but, in fact, this is simply a result of the infrared–the image was taken in spring after the snow had melted. This appearance is not uncommon with shrubbery and trees.

It is psychologically more comfortable to transform this image by using the monochrome function which also, in my view, reveals a bit more by sharpening the image.

This next scene is part of our side-yard and this is a very dominantly green scene.

However, infrared and especially the monochrome transformation show us that green becomes snow-colored with infrared.

Furthermore, infrared/monochrome reveals to us that tulips are really albino plants.

Visually things start to get really interesting when we begin to look at insect structures. Consider the remarkable detail of the hairs on this fly.

It is even more remarkable when the infrared image is transformed to monochrome.

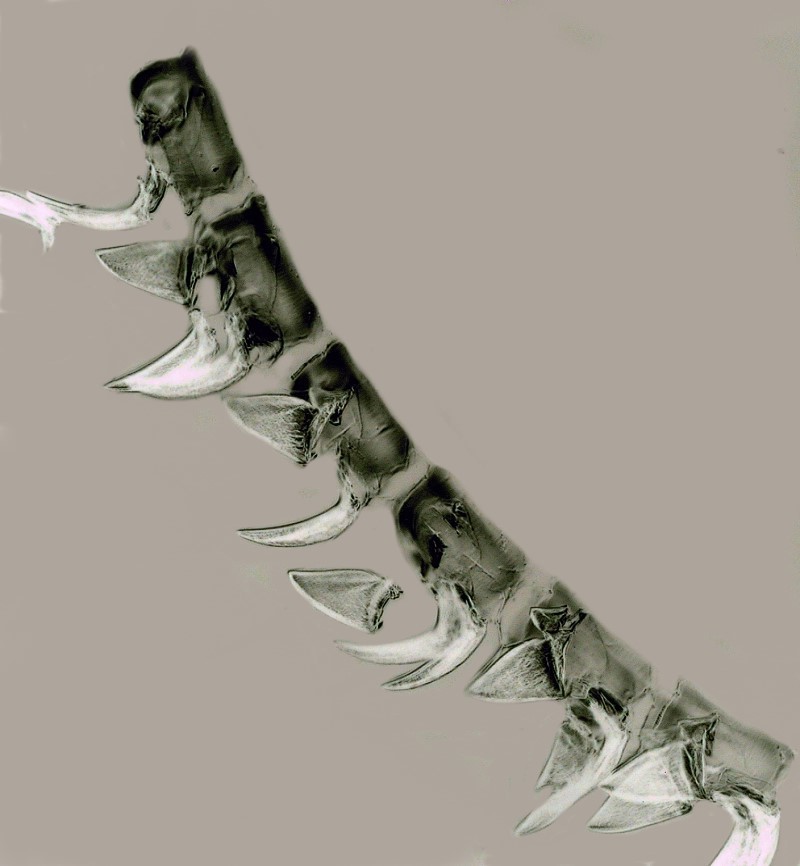

And here is the foot of a fly–an interesting structure of an obnoxious creature.

Dave Walker has done a fascinating article in which he uses a modified system employing a video camera. He presents some images of insects which using near infrared produces results that almost look like X-rays.

Perhaps the most interesting results which I have obtained thus far are of a radula and some of sea cucumber spicules.

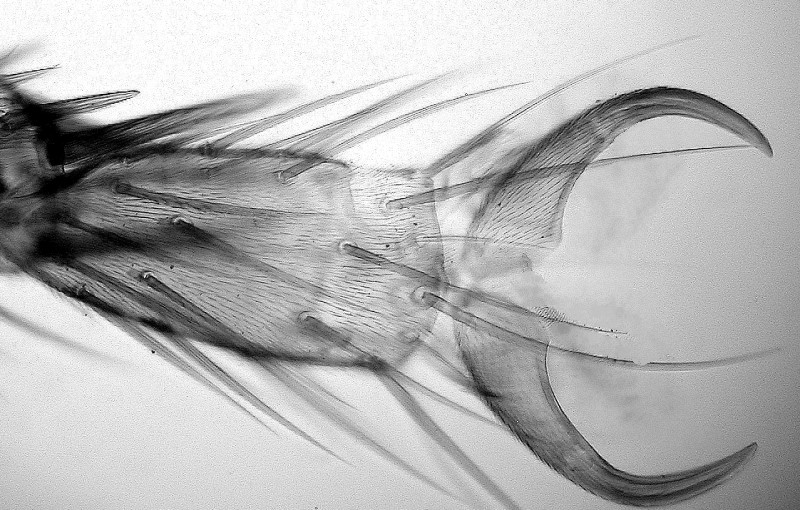

Let’s start with the radula. A valuable lesson which I learned from experimenting with this image is that one can produce some views that provide enhanced contrast and interesting shifts in perspective.

Then, by shifting the light level, cropping the image very slightly, and altering the background, I was able to achieve an image in which the teeth were emphasized, but in which the tissue was rendered more transparent in such a way that a bit more detail is revealed.

Now, by applying the INVERSE function to this image, we can see the teeth as being pseudo-transparent while the tissue is rendered semi-opaque creating an interesting contrast.

It next occurred to me that it might be worthwhile to look at the teeth quite apart from any surrounding tissue, so I created a white background and painted out all of the tissue. Here is the result.

Then I thought, why not apply the INVERSE function to this image and see what it produces and here again there are some nice subtle visual hints regarding structure within the teeth.

Finally, I took a few images of calcareous spicules from a sea cucumber and I’ll show you 2 of them.

Note that in the largest spicule near the center, there are some diffraction patterns which suggest a bit about the complex morphology of these crystalline structures.

And here is an image which shows some of the variety of types of spicules in this same sea cucumber.

As with most optical techniques, one has to select the “right” sort of specimen types. Clearly, infrared will not give useful results with all types and so it is important to choose those which allow one to explore the dimensions that are unique to this approach. I look forward to doing some further investigations with a different range of specimens in the near future and if I find some intriguing goodies, I’ll share them with you.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Richard remarks that the near infrared images were taken with a secondhand Nikon Coolpix 995 that had previously been modified for NIR imagery.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the November 2016 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .