Images by Jan Parmentier (NL)

Text By Brian Darnton (GB)

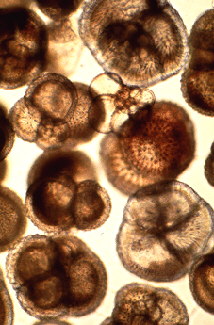

Greenhouse effect.

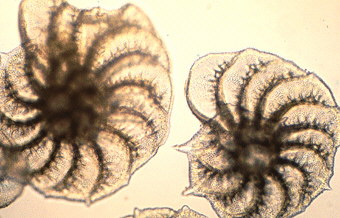

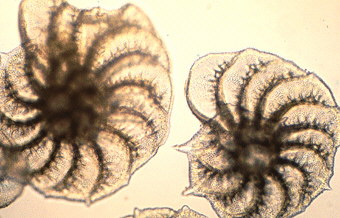

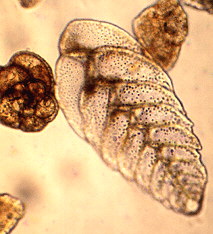

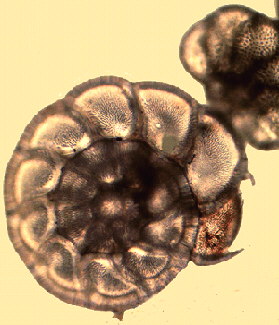

Greenhouse effect. The bays of the Irish and

Scottish Atlantic coast like Dogs

Bay (Ireland) and Calgary Bay (Isle of Mull) are excellent

sites where the forams are blown into dunes. Pure cultures can

discovered growing on seaweed in the early summer. The common

Foram Elphidium crispum enjoys the Sargassum muticum

fronds along the Southern English coast. In the Netherlands there

can be some confusion. In tidal lagoons like at Het Zwin, and

broad estuaries like the WesterSchelde, fossil Forams may be

found alongside recent ones as much of the Zeeland landscape

consists of covered or exposed tertiary beds. The United Kingdom

also has a few similar sites: Bracklesham Bay is a good example

of an area where Tertiary beds have an input into the marine

debris.

The bays of the Irish and

Scottish Atlantic coast like Dogs

Bay (Ireland) and Calgary Bay (Isle of Mull) are excellent

sites where the forams are blown into dunes. Pure cultures can

discovered growing on seaweed in the early summer. The common

Foram Elphidium crispum enjoys the Sargassum muticum

fronds along the Southern English coast. In the Netherlands there

can be some confusion. In tidal lagoons like at Het Zwin, and

broad estuaries like the WesterSchelde, fossil Forams may be

found alongside recent ones as much of the Zeeland landscape

consists of covered or exposed tertiary beds. The United Kingdom

also has a few similar sites: Bracklesham Bay is a good example

of an area where Tertiary beds have an input into the marine

debris.

|

In the bay situation the spread of Foraminifera is confined to a very limited deposition zone which is to be found towards the headland from which the tidal flow originates. Local newspapers usually indicate which local harbours have the earlier high tide times. Frequently the sample is marred by particles of discarded coal or natural lignite but the black and white banding is a useful indicator at the deposition zones. In the Mediterranean Sea the Foraminifera are numerous but because of the lack of strong tides, the deposition zone extends to most of the sandy coastline with large numbers to be found to the lee of headlands. In the open sea, depressions in the sand near submerged rocks can reveal pockets of "Shells" In gathering from the shore a good X10 hand lens is a useful tool and material is best scraped from the sand with a flat children's spade. Do not forget to label samples in a plastic bag. |

Cleaning.

Cleaning.

This suspension may be

decanted off into a 50 micron sieve or a fine sieve may be used

to fish for forams in the suspension. If the bucket is carefully

emptied and filled with a tap water at pressure some of the

forams will fill with air and float on the surface for a while

and may be captured. The Mediterranean types float well. The

physical separation from sand can become the most challenging

part of the business. When a fairly pure mixture of Forams has

been cleaned then sieves can be used to separate species. Each

seems to have a well defined size.

This suspension may be

decanted off into a 50 micron sieve or a fine sieve may be used

to fish for forams in the suspension. If the bucket is carefully

emptied and filled with a tap water at pressure some of the

forams will fill with air and float on the surface for a while

and may be captured. The Mediterranean types float well. The

physical separation from sand can become the most challenging

part of the business. When a fairly pure mixture of Forams has

been cleaned then sieves can be used to separate species. Each

seems to have a well defined size.

Smaller "Shells"

less than 100 microns may be strewn in water and when dry mounted

in Numount or a similar mountant. Its always a good idea to smear

the slide first with a trace of gum tragacanth paste in order to

prevent the "Shells "moving after mounting. Bubbles

emerge after mounting in Numount for about five days and can

spoil the mount. It is best not to use any heat for a week. The

larger faction will probably have to be dry mounted. A fine oooo

art brush is a good tool for manual selection. Here again Gum

tragacanth is a suitable adhesive because it tends to leave no

unsightly smear. At first, a simple 1 mm deep cell with a black

background is very suitable but when one becomes familiar with

species then some form of numbered grid is a good idea. NBS do

produce some plastic cell slides which are very useful for this

work.

Smaller "Shells"

less than 100 microns may be strewn in water and when dry mounted

in Numount or a similar mountant. Its always a good idea to smear

the slide first with a trace of gum tragacanth paste in order to

prevent the "Shells "moving after mounting. Bubbles

emerge after mounting in Numount for about five days and can

spoil the mount. It is best not to use any heat for a week. The

larger faction will probably have to be dry mounted. A fine oooo

art brush is a good tool for manual selection. Here again Gum

tragacanth is a suitable adhesive because it tends to leave no

unsightly smear. At first, a simple 1 mm deep cell with a black

background is very suitable but when one becomes familiar with

species then some form of numbered grid is a good idea. NBS do

produce some plastic cell slides which are very useful for this

work. Comments to the author Brian Darnton welcomed.

J.W.Murray. "An Atlas of Recent Foraminifera" 1971, ISBN 0 435 62430 X, Heinemann Press with 96 ESM plates

R.W.Jones "The Challenger Foraminifera" 1994, ISBN 19 854096 5, Oxford University Scientific Press

J.A.Cushman " Foraminifera" 1980 fifth printing, SBN 674 30802 8, Harvard University Press.

Tregouboff G an Rose M. 1957 "Manuel de Planctonologie de Mediterraneenne" (2 volumes).

Faber Dr.F.J "Geologie van Nederland" Deel 3 Nederlandsche Landschappen.

Editor's note: to read other Micscape articles on Foraminifera by Brian Darnton enter 'Foraminifera' into our Library Search engine.

Published in November 1998 Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK