Slipping and Sliding - Bacillaria paxillifer

by Ron Neumeyer, Canada

www.microimaging.ca

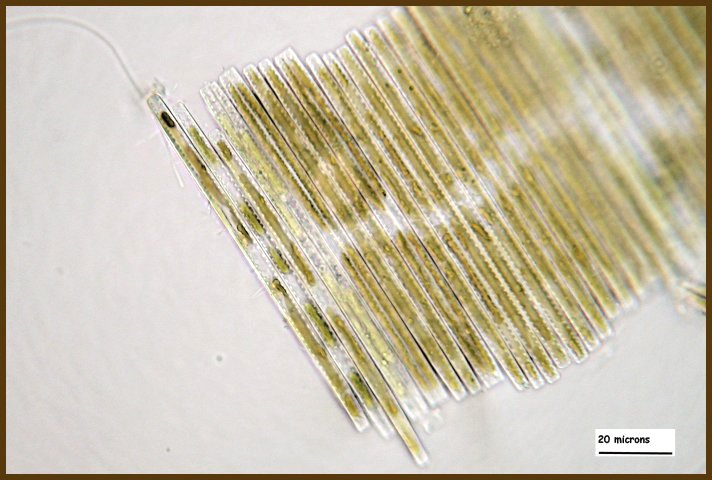

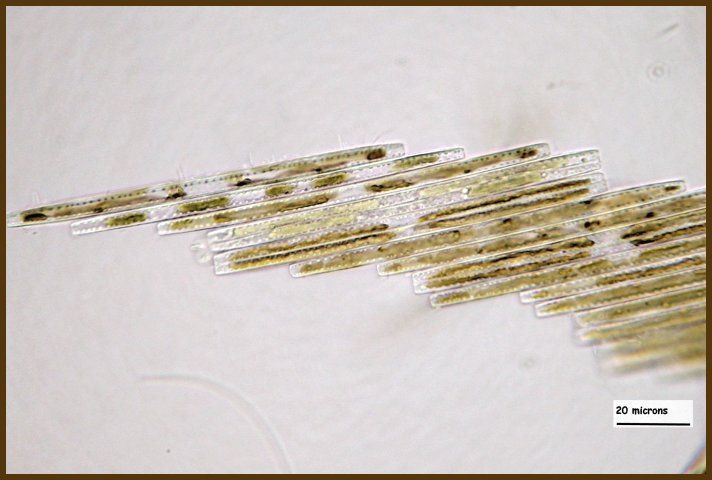

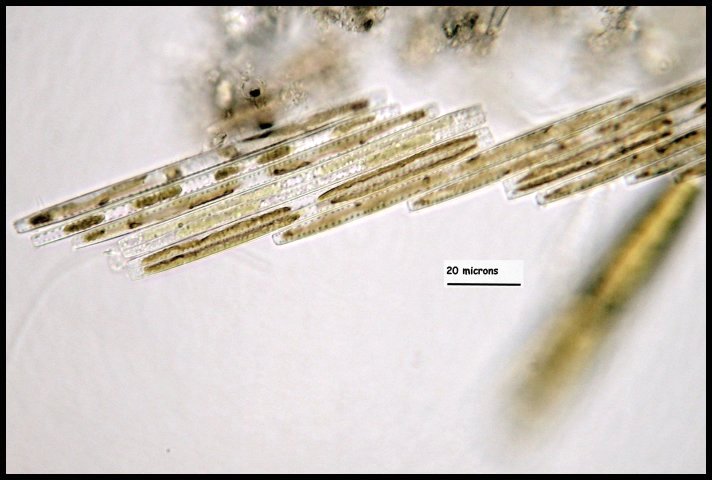

Bacillaria paxillifer (also known as B. paradoxa) is easily recognized when alive. It produces unique motile colonies in which the cells, though linked to each other via a ridge and groove arrangement of their raphe systems, are able to move over each other, so that the colony can alternate between a side to side chain (figure 1) and an extended, fibre-like configuration (figure 2, 3 and 4), in which each cell is connected to its neighbour only by the last quarter or so of its length.

|

|

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|

|

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

A search of the Internet reveals that diatom motility is generally confined to those pennates which possess the “raphe” - a long slit through the wall. The mechanism of motility has generated much speculation and now a good general understanding seems to have been reached. According to information on the Internet the jerky, irregular movement typical of raphid diatoms is generated by the active secretion of mucilage through one or two specialized pores at the end of the cell. The mucilage swells by uptake of water and pushes the cell along. (This form of motility is quite common elsewhere, for example, in desmids.)

As noted by Wim in his earlier article on this diatom, the interlinking of the raphe systems results in very fast movement between the compressed and extended forms of the colonies. I timed a few colonies and found the change to take about 10 seconds once it is initiated. Using the Coolpix motion capture mode I have put together a short video of this motion (click "video" to view, 2 Mbytes in Windows wmv format).

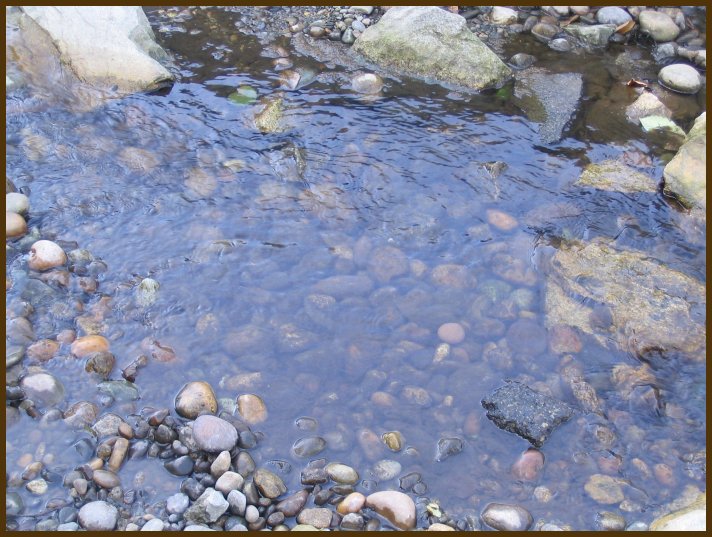

This diatom was found in a low gradient freshwater creek (figures 5 and6). The filamentous algae covering the cobble stones provided a habitat for the Bacillaria. The stream had a temperature of 72 degrees and a pH of 7.2. The area has had no significant rainfall for 30 days or so.