With various microscopy projects in progress but none at completion to share, this is an admittedly rather self-indulgent ramble for this month's issue. It reflects on various aspects of books that hopefully others can relate to, using examples from my own collection.

A lack of space seems to be no excuse to stem the book buying 'addiction'

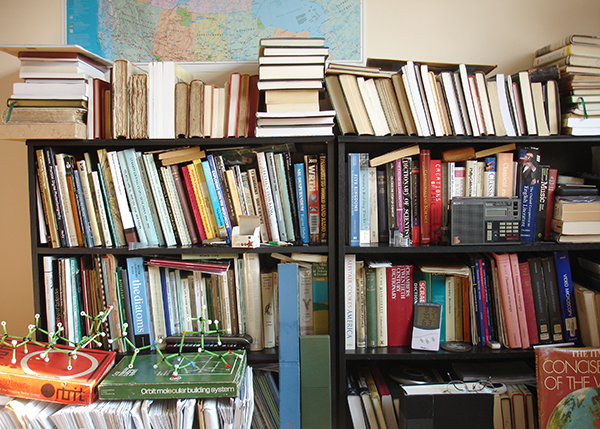

The image below is I suspect a typical scenario in many fellow microscopy enthusiast's houses. I have quite a modest book collection with none of the floor to ceiling populated bookshelves seen in some lucky folk's abodes. But I do live in a fairly modern house where the designers seem to have forgotten the importance of plentiful storage space. The logical solution is either to stop buying any more or to totally embrace the paperless age (more on the latter aspect later). But logic doesn't seem

to apply to the book lover. Attempts to keep books neatly ordered in shelving have long since been abandoned. Newly acquired books are squeezed into any remaining space and the final solution is to stack them flat on top until either the ceiling prevents further progress or the floorboards collapse under the stress.

An overstretched bookcase likely typical of many reader's houses? Some clues to other interests can be seen. Collecting slide rules, the two slim vertical boxes enclose 20 and 10 inch models by Nestler and Faber-Castell. The large map of Northern Canada reflects an interest in the fascinating history of the search for the North West Passage. The molecular model kit comes from my college days studying chemistry in the 70s and in idle moments like to build naturally occurring molecules (my alternative to adult colouring books or large jigsaws as a gentle pastime!). The models shown are testosterone and penicillin. The Sony world radio reflects a past interest in radio DX-ing but is now just used for local radio as the airwaves are too cluttered with interference in my area.

Books that recall memories of where bought

Books that recall memories of where bought

With the increasing demise of the bricks and mortar used bookshop which has now been replaced with portals such as Abe, Alibris and Amazon Marketplace, most of my books bought since the mid 90s have been purchased online. None of these books when handled raise memories of where bought. But some of my older books do, bought before the rise of the Web. The example right is one such book.

I was at a deserted Staines, Middlesex railway station some years ago in winter waiting for a late train home. To keep out of the bitterly cold wind I waited in the small ticket hall. This station had a row of unattended used books for sale on a bench and a buyer was invited to pick one and put whatever monies seemed reasonable into the charity box embedded in the wall. With no reading matter for the journey home I scanned what was on offer. I chose the classic 'Possible Worlds' by J B S Haldane, this example was a cheaply produced wartime paperback dated 1940.

They are a delightful series of essays by a noted scientist and popular writer (see his Wikipedia entry). 'The Cambridge Dictionary of Scientists' 1996 has an entry for him which includes the remark that 'Haldane is one of the most eccentric figures in modern science'. There are no doubt much more finely bound more recent editions but I have a fondness for this cheaply acquired edition because of the clear memory of how I acquired this example.

A library's loss but the private buyers gain, but why are some modern books discarded?

A library's loss but the private buyers gain, but why are some modern books discarded?

The used book buyer will be very familiar with the pros and cons of buying unseen the 'ex-library' copies. The bookdealer's descriptions are often almost apologetic describing the peeled off labels, possibly well used etc. But on the positive side, if the contents are sound they can be the cheapest, any dustcover may been protected at purchase and is often the type of edition I seek out on a budget. I can appreciate why the often very dated books on

various specialist topics can be discarded by a library but I am increasingly finding very recent books that have suffered the same fate. An example is shown right.

This biography by Joseph P Ferry of Maria Goeppert Mayer, a Nobel Prize winning physicist, was published in 2003. It is well produced, well written and has excellent illustrations. This seems a potentially inspirational book, particularly for a young lady considering the career path of a scientist. Apparently the Plainville Public Library, MA didn't think so and has been stamped 'Discarded'.

Another example not shown is my copy of Colin Tudge's delightful 'The Variety of Life. A survey and a celebration of all the creatures that have ever lived'. My edition was published in 2002 and seems a very useful addition to any library as a very accessible path through the minefield of modern systematics. The 'Library Boston University' in Harrington Gardens, London didn't seem to agree and is stamped 'Withdrawn'.

The unexpected bonus - a previous owner's bookmark

The unexpected bonus - a previous owner's bookmark

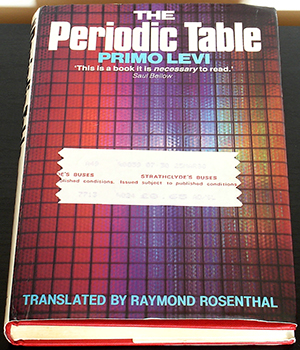

One of the unexpected additions of buying a used book is what may still be enclosed as legacies from previous owners. Examples from my purchases include a faded unwritten early 19thC postcard of a man and his dog—significance unknown and a typewritten letter from an owner to a third party on microscope accessories for sale and various newspaper clippings. My most recent example is perhaps the most mundane, it's just a Scottish bus ticket, priced and dated. But for no real

reason it has been retained as my bookmark for this copy.

I wonder whether the previous owner enjoyed reading the book on a Strathclyde bus at 0730 on Friday March 25th 1988—perhaps on their way to work—a snapshot in time.

This book is shown right 'The Periodic Table' by Primo Levi (Italian edition 1974, English edition 1985). With a chemistry work background perhaps I ought to have known about this classic book but admit that I didn't until BBC Radio 4 recently broadcast a daily series based on the book. This prompted me to buy a copy and was an enjoyable and thought provoking read. The Wikipedia entry notes that "In 2006, the Royal Institution of Great Britain named it the best science book ever." Each chapter is devoted to an element where the author cleverly weaves a story based on his life experiences including as a chemist before, during and after WWII.

A bookbinding puzzle

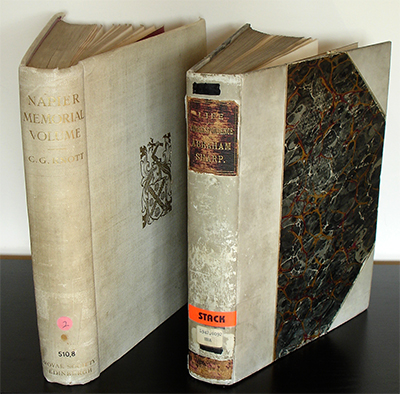

If any readers are familiar with 19th and early 20th century bookbinding, perhaps they can solve a puzzle that intrigues me. A number of my books of this period on various subjects have the same type of binding inconsistency. Two examples are below. Both have good quality contemporary bindings with some attractive tooling and neatly trimmed page edges on the top with gold leaf finish. But inspect the sides and base of these books and they are very ragged indeed (they

stand out noticeably at top left image of the bookshelves). I have so many examples that they can't all have accidentally missed the final trimming. I can only assume the printers and binders weren't too bothered and neither presumably were the booksellers (or buyers?). Many much cheaper books owned both earlier of similar period have been neatly trimmed on all page edges. Any insight appreciated!

Left above - 'Napier Tercentenary Memorial Volume' edited by C G Knott, Longmans, 1915. Published for the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Right above - 'Life and Correspondence of Abraham Sharp' by W Cudworth, Sampson Low, 1889.

Both high quality bound volumes ... until notice the very scruffy page edges and bases due to the total absence of any page trimming (right above).

Poor trimming can be understandable for cheaper book editions such as the uppermost example right and which can be much worse.

The pros and cons of electronic books and modern facsimiles of old books

The pros and cons of electronic books and modern facsimiles of old books

Like many readers no doubt, although a lover of hard copy books I've embraced the digital age and what it has to offer. Resources such as the Internet Archive and Google Books has allowed instant access to many books out of print and journals now in the public domain that would be hard to access readily. The ease at which such resources have aided studies is inestimable, especially when coupled with Google's ability to search text in books scanned as

images. But there is

the accompanying dilemma.

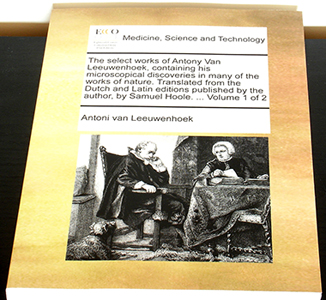

I've never got to grips with formats such as Acrobat pdf for extensive book reading, they don't have that indefinable tactile pleasure of a hard copy or the practicality of flipping pages back and forth to check former entries. If at all possible for online scanned books of particular interest I do seek out an affordable original hard copy. But for many books they would be too expensive and an example is shown right.

With a particular interest in Van Leeuwenhoek I'd like a copy of Hoole's two volume 'The Select Works ...' ca. 1807 but they are rare and not affordable. So have had to make do with the typical modern facsimile printed off www.archive.org or Google Books by one of the many publishers of facsimiles from these sources. I dislike these often poorly printed editions though and barely tolerate them. I've sent a number back to the sellers and written to one publisher gently suggesting that they if they are going to ask money for a facsimile, to please seek out and scan from an original and ensure fold-out illustrations are folded out before scanning!

The satisfaction of repairing 'distressed' books

The satisfaction of repairing 'distressed' books

Most of my old books, as remarked, are the cheaper examples as long as the content is complete and sound. Some may be very 'distressed' with detached covers, loose pages and/or binding etc. I can't justify the cost of having them professionally restored but it's satisfying to repair them in a sympathetic way (i.e no Sellotape!) to give a robust working copy.

Materials such as brown envelopes, lightweight grades of beige paper coupled with professional mending tape and bookbinding glue doesn't cost much but can affect a reasonable repair to allow a book to have a longer working life.

The Lineco 'Mending Tissue' shown is a typical type and is superb at repairing paper tears or stiffening the edges of brittle paper to give an almost invisible repair and is near transparent so can overlay text. The material is acid free and of archival quality.

The book shown had both covers detached on receipt so was in desperate need of repair.

Niggling thoughts of the book lover but partly pacified by Winston Churchill's essay on 'Hobbies'

Niggling thoughts of the book lover but partly pacified by Winston Churchill's essay on 'Hobbies'

I'm sure fellow readers may have had one or more of the following thoughts cross their mind as their library continues to increase in size:

- I have plenty of books only partly or not even read yet, why do I want to buy yet another? (My own excuse is that many are reference books where they are dipped into rather than read from cover to cover.)

- Despite enjoying reading a book, on completion I'd be struggling to remember and recount much of it so why did I bother? (An increasingly common query for me as I get older. I sometimes write brief summaries of key points to aid my memory.)

- There is no space left, I have too many, at some stage I need to stop buying any more and embrace a Kindle or similar electronic book reader. (Especially if the daunting task of packing and storing them for any potential house move arises.)

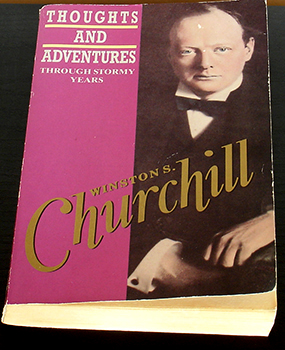

I can't offer any answers for the above imponderables but for at least the first I greatly enjoy Winston Churchill's thoughts on books related in his essay 'Hobbies'. I won't spoil it by quoting and invite readers to seek out a copy if it's unfamiliar. He has another splendid essay on amateur painting although I'm not a painter. They form part of a collection of essays entitled 'Thoughts and Adventures. Through Stormy Years' first published in 1932. The example right is a good value 1990 paperback edition, this and other editions are readily available.

If you could only rescue one book in a calamity, which would it be? Annotations make an old book unique.

Heaven forbid there would be an impending calamity that forced a rapid house evacuation prior to its potential destruction. But after ensuring the safety of occupants and grabbing if there's time a handful of the essential house documents, which single book would you want to save from your collection and why? This is a very easy question for me to answer. Like many hobbyists on a budget, it is the content that is key and most of mine including the 19th

century microscopy classics are replaceable. They are often the well used, ex-library type examples rather than the finely bound. Admittedly, some books and often modern would be a long struggle to replace cheaply. It was some years before an affordable example of Ford's splendid 'Leeuwenhoek Legacy' turned up, and Rost's two volume 'Fluorescence Microscopy' was bought just before the prices became too silly (especially Vol. 2).

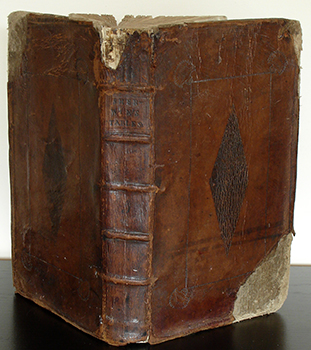

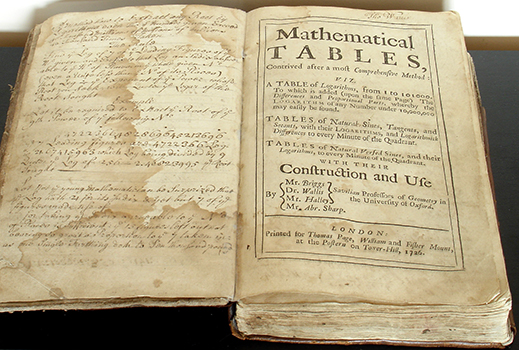

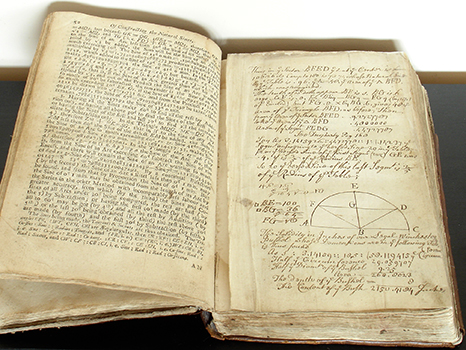

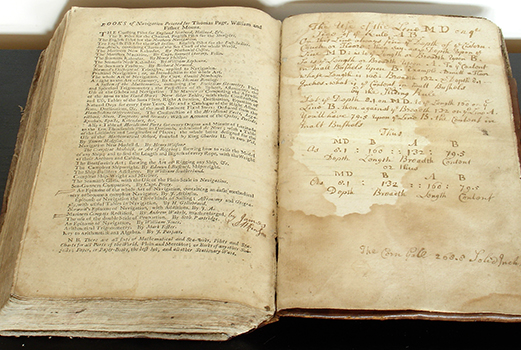

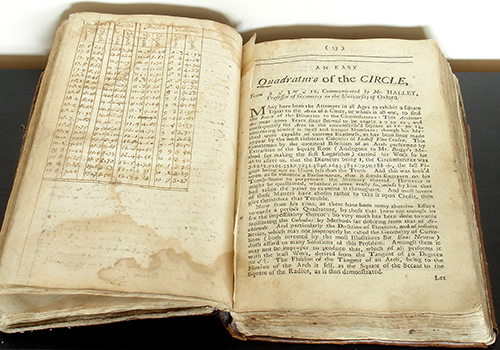

The one irreplaceable book in my collection is a copy of 'Sherwin's Tables', a second edition 1726. Books of this era are usually beyond my budget but this sad looking, water stained although complete copy, was in budget. My interest in the history of logarithms and tables and the associated personalities is a spin-off from my interest in slide rules coupled with the quadricentenary of John Napier's publication of his table of logarithms in 2014. Original copies in themselves aren't that rare but it is a book's annotations when present that make each unique and this example has every spare space neatly filled with copperplate notes by one or more owners. The notes reveal at least one owner had a particular interest in the maths associated with brewing. It has notes on measuring the volume of malt on brewing floors and a guide on how to use a slide rule of the period for such calculations.

Sherwin's Tables are a compilation noted by historians as an important member of the lineage of published tables yet almost nothing is known of Henry Sherwin who compiled and published them. I'm currently trying to research the biography of the compiler.

Annotation in modern books can reduce their value although can be useful for those seeking budget copies if the text, for example, is heavily marked with biro by a student when studying. But for me, older books with annotations are a bonus. My copy of Hogg's 'The Microscope' 1871 (6th edition) has tiny copperplate handwriting which extensively annotates the author's text and gives this copy character.

'Sherwin's Tables' 1726, second edition. As well as tables compiled from the work of Briggs, Wallis and Sharp, it has a series of essays.

The tables include both logarithmic and trigonometric functions. Logarithms of whole numbers from 1 - 100 as calculated by Briggs are given to over fifty decimal places and logs from 1 - 101 000 are to eight figures—quite a feat of calculation by hand and don't envy the publisher's typesetters!

The blank righthand page and every other blank page as shown below is used for one or more previous owner's notes. The content dates them to the 18th century.

Left above. Handwritten notes on how to use a slide rule of the period to calculate the volume of grain on a malting floor. The page right is one author's own tables giving conversion factors associated with brewing.