|

The Weirdest of the Weird (Excluding Human Beings) by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Again and again, I have asserted that nature is always experimenting and in the process produces some deeply bizarre creatures. We have a profound fascination regarding the possibility of alien life forms on other planets and are willing to spend billions of dollars trying to find examples, while we are surrounded by alien life forms right here on our own planet, organisms which we could discover and investigate at a much more reasonable cost and some of the research could provide enormously practical benefits. I realize that I am equivocating here when I use the word “alien”, because most people want to know about the possibility of life forms on other worlds, planets other than Earth. The practical difficulties of making such a determination are so immense and so expensive, at least with our present limited technologies, that it makes much more sense to try to understand (and save) our own planet.

Here I want to provide just a brief introduction to some groups of organisms that have astounding characteristics and yet most of these creatures remain completely or largely unknown to the vast majority of us. (Many of you already know that when I say “brief”, I mean less than 100 pages.) We know that life is capable of adapting to extraordinary circumstances: pink algae that smell like watermelon and grow on snow banks, cyanobacteria which live in the hot springs of Yellowstone Park, bacteria which live in salt caves, brine shrimp which live in the Great Salt Lake, giant tube worms with bright red tentacles which live under enormous pressure in the depths of the sea, as well as other organisms that live around volcanic funes and metabolize sulfur compounds in the darkness where photosynthesis would be impossible, and this is just to mention a few examples.

We all know that there are many elegantly beautiful organisms, but that will be a topic for another essay. The creatures we will be taking a glance at certainly won’t be beautiful, but they are intriguing. Let’s begin with some worms; every adolescent boy loves worms as a means to torment his sisters. There are giant earthworms in Australia that reach a length of almost 10 feet!–Imagine what you could catch with one of those on your fishhook. Fishermen along the seashore often use “clam worms” or Nereids as bait. You can find these out in the mud flats if you dig fast. I was going to show you an image or two, but when I went down to my storage space in the basement, I couldn’t find the jar. So, you’ll have to settle for a link which will show you a nice variety.

However, I’ll substitute something as good if not better, Amphitrite, named after the wife of Poseidon. This one is about 6 inches long and all of the spaghetti stuff at one end is tentacles. In addition, this worm possesses gills which are a bright red when it is alive. It burrows on mud flats and extends the tentacles out over the surface seeking food.

Put one of these in your sister’s lunch box if you want to hear a shriek that will shatter glass and earn you a suspension from all TV and video games for the next 6 months. When you look at the close-up above, you know that those tentacles will thrill your sister. However, if you want to produce the pinnacle of revulsion, the Mount Everest of disgust, then the “sea mouse” (Aphrodite aculeata) is the worm of choice. The zoologist, Linnaeus, who gave this creature its name may have had a very wry sense of humor, since Aphrodite was, among other things, the goddess of beauty. However, it has also been suggested that this creature was named because it was thought that the ventral side resembled human female genitalia in appearance.

Our Aphrodite can grow to about 8 inches in length and nearly 3 inches in width and over 1 ½ inches thick. It is a scavenger at the bottoms of bays and lagoons and is covered with the constant rain of detritus falling down on it as it feeds, plus its dorsal aspect is further glorified by a rather abundant growth of algae. And here are 2 images of our lady of the moment, one from the top and the other of the underside:

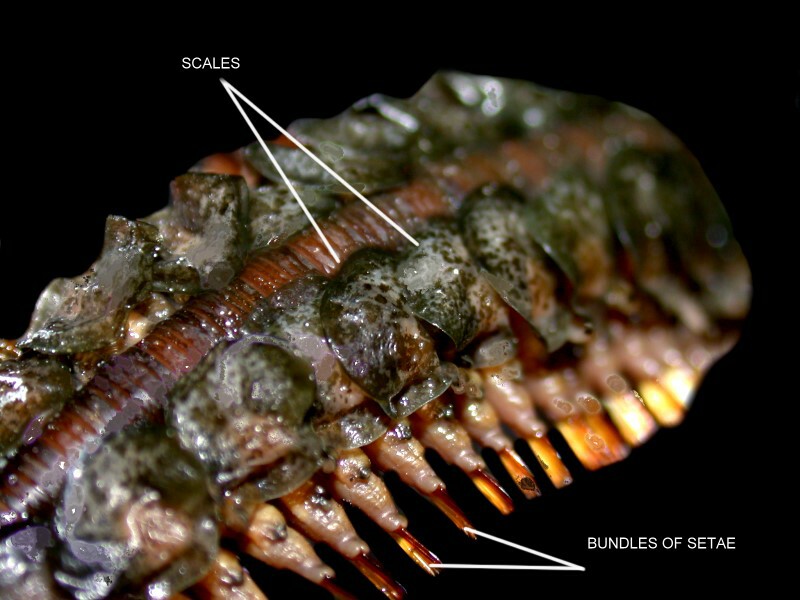

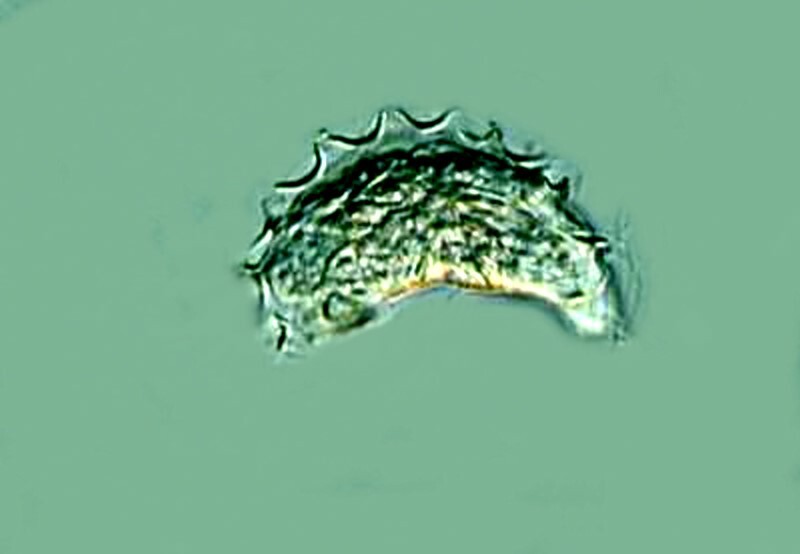

However, when one scrapes all of the muck off, one discovers that we are dealing with a giant scale worm which has 15 pairs of scales on its back. The specimens have been preserved for over 30 years and the scales have deteriorated severely. Instead, I’ll show you another type of scale worm and a close-up of a scale and also some setae (bristles).

Look at the image below and imagine having “fingernails” like these and rows of them extending up and down both sides of your body.

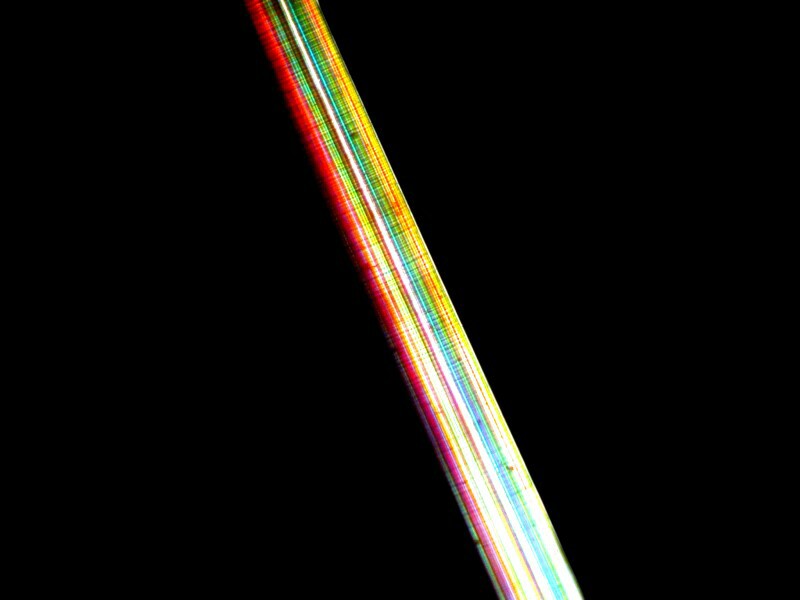

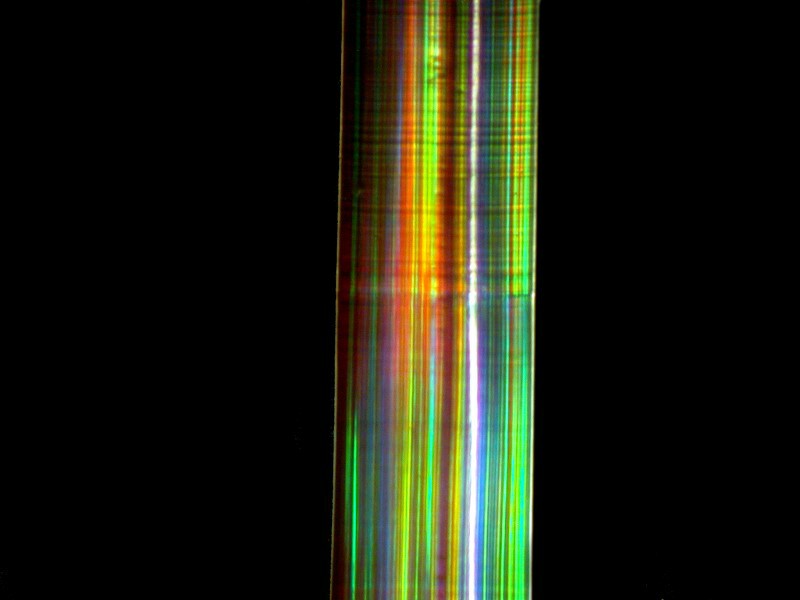

Aphrodite also possesses 2 kinds of bristles, one of which is composed of an incredible number of hexagonal crystals which are more efficient thus far at light transmission than any of our fiber optics. These bristles are wonderfully iridescent in the right lighting. In other words, a creature worthy of an essay unto itself.

A creature which I have discussed elsewhere (thus, it doesn’t need a separate essay–sigh of relief on your part) is the “spittle bug” which I find most every summer on the junipers in our front yard. This is a creature which could have been conceived by H.R. Giger, the master illustrator of the Alien movie series. This is certainly not a creature that you would want to cuddle up to.

You see, just by looking in your own immediate vicinity, you can discover all kinds of alien life forms; why spend billions on space projects?

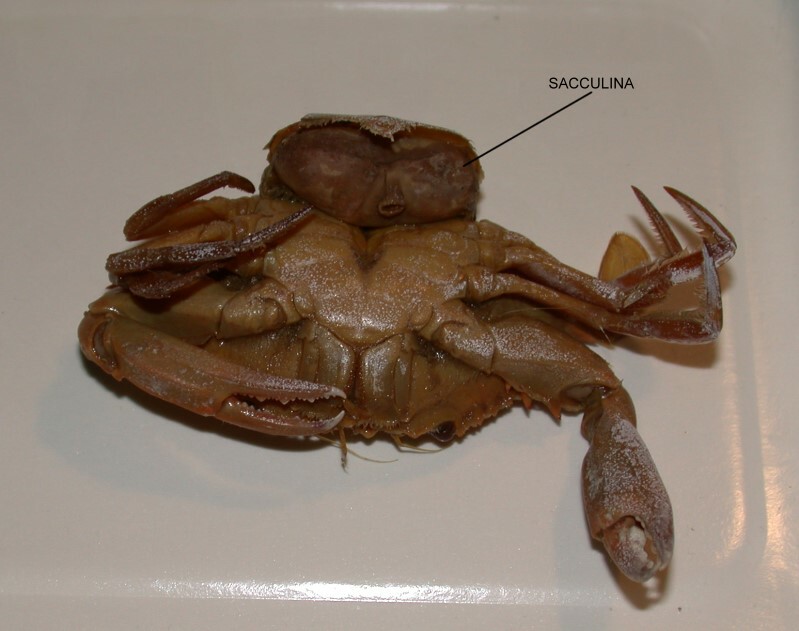

A creature which certainly deserves one of my long, rambling essays at some future date is Sacculina. The search for these is best done with preserved specimens in your own lab or, if you insist on look for living specimens, do so on a beach where you will be unobserved by strangers, otherwise they may well use their cell phones to dial 911 to report that some strange, wild person is running around the beach sexually molesting blue crabs. Sacculina is a parasitic barnacle, the larva of which finds a join in the body of the crab and then injects soft parts through the opening and migrates to the area of the genital flap. What happens next is the stuff of science fiction. It begins to send out a network of tiny tubes like a root system throughout the body of the crab, even into the eye stalks. It uses this network to nourish an orange reproductive sack that forms under the genital flap of the crab and, in the process, neuters the crab–it can no longer reproduce. However, Sacculina is one of those clever parasites that doesn’t kill its host; the crab is reduced to a kind of zombie which continues to feed and function in order to maintain Sacculina. And how about this–over 100 species of Sacculina have been identified! Here is an infected crab which from this perspective looks quite ordinary and usual.

However, when we turn it over, we can see the parasite bulging from beneath the genital flap.

And here is a close-up that any sci-fi fan will immediately recognize as an inspiration for Jabba the Hutt.

You can think of this the next time you are enjoying a nice crab salad or crab cake.

Since we have a sexual theme going on here (biologists are always preoccupied with sex), let’s take a moment or two to consider some unusual behavior in invertebrates and protists that has to do with reproduction. We think human sexuality is complicated and given the psychological, as well as the biological, aspects, it is indeed, in its own way. However, imagine the complications for an organism with at least 5 distinct biological sexes, such as, some of the symbiot protists that live in the gut of termites and wood roaches. I’ll show you 3 examples from a termite. The first is a long, slender organism with a tuft of very long flagella. It is called Streblomastix.

The next one is intriguing to watch because its motion is unique; the undulating membrane across the back moves in such a fashion that it looks like a miniature chainsaw. It’s name is Trichomitopsis.

The third one is remarkably complex and has been fairly extensively studied. It is Trichonympha and it looks like it has a mane of long hair. These are flagella and some biologists believe them to be originally derived from bacteria that became symbionts. The cone-shaped projection in the upper part of the image is where one would ordinarily expect to find a mouth or cytostome, however, not with this beastie. The food particles, wood ingested by the termite, are taken in along the long curving area at the other end of the organism. You can see that these particles are slightly birefringent and this is a consequence of their cellulose composition. The ovoid structure just above center is the macronucleus.

A case can even be made that for certain ciliate protozoa there are even more “sexes” or “mating types”. Paramecium aurelia has been most extensively studied in this regard and no one knows exactly how many mating types there are because, so far, no one has found any determining morphological characteristics and so, these distinctions likely occur at a biochemical and biophysical level that scientists have not yet been able to analyze. Paramecia can divide about 200 to 250 times and then they need to conjugate, that is, have sex. This occurs when 2 individuals fuse a portion of the membranes and exchange nuclear material.

The process is fascinating and complex and you can find good, detailed accounts of it. After the exchange takes place the two organisms separate and are revitalized and can then start a new cycle of reproducing by division again–well, most of the time. There is a Paramecium that contains within it a minute structure called the Kappa particles which are thought to be viroids or perhaps prions. When conjugation occurs some of these particles are passed to the non-Kappa strain and ultimately prove lethal to it, thus allowing the Kappa strain a kind of biological dominance. Here is a good project for some mad scientist: to attempt to engineer a human equivalent of the Kappa particle which affects corrupt politicians and financial types.

In the realm of sex in the invertebrate world, there are indeed some sinister things afoot. We males can learn some disconcerting facts from studying invertebrate reproductive processes, not to mention the fact, that all human fetuses are initially female and its only after some weeks that there are hormonal triggers that can cause a fetus to be transformed into a male.

We have all heard the story of how the female praying mantis devours the male after mating and there are a considerable number of spiders which engage in such behavior as well, which is one of the reasons that male spiders have developed means of transmitting sperm to the female by means of a front pedipalp to increase his chances of surviving after having performed his ritualistic duty.

To stray from the invertebrate realm for a moment, there is a species of deep sea fish in which the male is tiny in relation to the female. The male attaches to her in the area of the genital pore and her tissue grows around him thus imprisoning him and turning him into a sex slave.

Sexual identity is not really as determined and fixed biologically as we might think. Among certain kinds of reef fish, there are occasions when there are too many females or too many males and so some of these change into the opposite sex–no surgery, no sex clinics; it’s an extraordinary mechanism which nature has devised to maintain species survival.

Back on the invertebrate beat, as we explore further, we find some even more disturbing examples, at least from the male perspective. There are some groups of rotifers and cladocerans (water fleas) in which no males have ever been found. These organisms reproduce exclusively parthenogenetically and, of course, all of the offspring are female. Apparently males are simply unnecessary. There are a few species where very small males are very occasionally found but, it is uncertain whether they any longer play any role in reproduction. So, perhaps human males should reconsider the roles of playing war games and the economic games of greed involving amassing unnecessary and outrageous amounts of wealth or we might find ourselves up against a radical underground feminist biology movement to clone and manipulate sperm cells and eliminate the male half of the human race.

And, just in case your male ego isn’t already feeling a bit battered, Mother Nature–the very name conveys the idea that the female principle is dominant and in control, which is what I think Goethe was suggesting in Part 2 of Faust when he speaks of the Mothers of Being–anyway, Mother Nature created a little crustacean called an ostracod or “seed shrimp” which in both relative and absolute sizes produces the largest sperm cells of any known organism and yet the entire organism is usually less than an inch in length. To achieve the same ratio, human sperm would have to be over 55 feet in length! The engineering involved in all of this is fascinating–and yes, worth a separate essay. Ostracods are very abundant and there are a number of freshwater species and even more marine ones. Furthermore, they have a long history and they produce a good fossil record. Below is first, a fossil ostracod and then below that the shell of a modern, freshwater form.

From our point of view, it is a remarkable and extraordinary thing that virtually every day, new organisms are being discovered–creatures which human beings have never seen before. That is indeed an incredible phenomenon but, from another viewpoint, I would argue that most people are so preoccupied out of necessity with survival or out of indifference and ignorance with trivia that they are largely oblivious of the world in which they live and the complex biological interactions and mechanisms that sustain them. So, in a very important sense, when the neophyte begins to look carefully at nature, study it, and examine it microscopically–every day can lead to a new and wonderful discovery for that person.

Nonetheless, there are regions where exploration is possible only with expensive and sophisticated tools, such as the remarkable submersible Alvin, and its kin. New technologies have allowed us to examine the abyssal depths that were once thought to be vast oceanic deserts essentially devoid of life. Wow! Were we ever wrong about that!

Creatures from virtually every invertebrate phylum had been discovered by the mid-1880s or so we believe at the moment. I strongly suspect that as we further probe the ocean depths, we are going to continue to find surprising organisms that don’t fit our current categories. It wasn’t until 1900 that a ship dredged up a strange worm-like creature off the coast of Indonesia. It was a pogonophore or “beard bearer” and they are almost exclusively deep sea forms which perhaps partially explains why no one had previously discovered them or noticed them. In the 19th Century especially, there was tremendous interest in discovering new marine species and numerous research expeditions were launched including those of the Beagle and the Challenger, just to mention two.

Now, something over 100 species of pogonophores have been described. Most range in size from about ½ an inch to 4 inches, but in the 1970s the submersible Alvin found specimens near a deep sea volcanic fune that were over 6 feet in length! Zoologists have constructed a variety of theories to explain how nutrition takes place and the dominant ones center around the tentacles–“beard”. Unfortunately, I don’t have any of these exotic creatures in my collection of specimens so I can only provide you with websites (A and B) where you can see some images and get further information.

Another interesting group of worm-like creatures is the Sipunculids or “peanut worms”. I have to include them, if for no other reason than it allows me to relate a wonderful, possibly apocryphal story which, however, is too good not to be true. These organisms possess an anterior introvert (no, nothing to do with socio-pseudo-psychology). The introvert is typically a fringe of tentacles or lobes around the mouth and behind that area, the surface usually possesses minute spines, tubercles, or even a calcareous shield. Those of you who know of my fascination with calcareous and siliceous structures in invertebrates will not be surprised that these creatures attracted my attention. In appearance, they are certainly not dramatic, but they are of considerable interest phylogenetically. I’ll show you 2 species; the first is Siphonomecus multicinctus and the second is Phascolosoma.

This brings me to my story of how they were allegedly discovered. Two zoologists were playing golf along a coastal area of Scotland (where else?) And one of them hit his ball out over a cliff and it landed on the beach. They scrambled down the cliff and began hunting for the ball which proved sufficiently elusive that they were driven to turning over rocks in their quest and, in the process, discovered an odd worm-like creature which was unfamiliar to them. As it turned out, their specimen was a “peanut worm” or sipunculid and they decided on a genus name designating the occasion of their discovery. The genus name Golfinga was assigned to it as a tribute to the game that led to their find and that genus name still survives today. So, clearly the story has “truthiosity” which is certainly several steps higher that “truthiness”.

For those of you who are interested in worm-like critters there are some erotically suggestive phyla. I will simply suggest that you look up Bonellia in the phylum Echiura and also the members of the phylum Priapulida and I’ll leave the rest to your imagination.

Another unusual and quite charming group of creatures is the “water bears” or tardigrades. Dave Walker, our splendid editor of Micscape, has confessed to a special fondness for tardigrades and you should read his articles on them and look carefully at his fine photographs.

There are over 350 species and the majority of them tend to live in the water films which surround aquatic mosses such as sphagnum. They are not uncommon, but one does have to look in the right places to find them and, I assure you, it’s well worth the effort. These tiny organisms have an extraordinary ability which science fiction writers (generally ignorant of tardigrades, I’m sure) employ as a device to get astronauts through the tedium and physiological rigors of long space journeys–namely “suspended animation”. The length of the life of a tardigrade is estimated to be between a few months to somewhat over 2 years–I emphasize that this is an estimate because virtually all such measurements are done in laboratories under the artificial conditions of cultures and as far as I know, no one has yet succeeded in attaching a radio transmitter tracking device to a tardigrade. However, with nanotechnologies, it may be only a matter of time.

During dry periods, tardigrades shrivel up, reduce their mass, reduce water content and go into a contracted, highly resistant state in which metabolism is radically reduced. This process is sometime referred to as crytobiosis and the consequences are incredible. Sadistic scientists have subjected these tiny creatures (almost all of them less than 1 mm in length) to the most extraordinary conditions, which include immersion in highly toxic solvents such as, acetone, 100% alcohol, anesthetics such as ether, high levels of salt concentrations, heat, and extreme cold (to less than -250 Centigrade), and a variety of narcotic substances and, what is truly astounding, is that some specimens survived these extreme conditions. The ability to transform oneself sounds absolutely perfect for space travelers and for those of us who find ourselves trapped in social situations surrounded by hordes of stupid and vacuous fellow humans. Tardigrades–under laboratory conditions–have been demonstrated to be able to survive for over 7 years! Certain types of rotifers also possess this remarkable transformative ability. When conditions become properly moist again, tardigrades and rotifers can reconstitute themselves and “hatch” in a matter of hours. Given the somewhat precarious conditions in which some of these organisms live with an alternation of moisture and dryness, they likely go through this process multiple times and so it is virtually impossible to determine their life span. For quite some time, there was a story circulating which claimed that a fragment of a dried sample of moss which was 125 years old had been taken from a museum case and placed in water resulting in the “hatch” of a few rotifers which became active but, only very briefly, and expired soon after. The story may well be apocryphal and I haven’t been able to find any confirmation but frankly, nature is so innovative that it wouldn’t really surprise me and scientists are so compulsively curious that taking a 125 year old moss sample and experimenting with it doesn’t surprise me in the least.

I realize that I have just barely scratched the surface when it comes to weird organisms and perhaps I can find time to produce some sequels in the future–Son of Weird Organisms 1, Son of Weird Organisms 2, Daughter of Weird Organisms 1, etc. However, one area that I do hope to be to able to explore in the not too distant future is the super-weird realm of parasites, the strangeness of which you can imagine from our brief discussion of Sacculina.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the December 2013 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .