|

A Trip Into The Past: Part 6 by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Part 1 : Part 2 : Part 3 : Part 4 : Part 5

In the last part, I ended up devoting the entire essay to a single issue of The American Magazine of Natural Science and you’ll be delighted (or depressed ) to know that I have 4 more issues. We started with Volume 2, No. 4 and I have Nos. 5,6,7, and 8 and I’m sure we’ll be able to find some entertaining and enlightening material. This time I’m going to start my discussion with one of the articles: “A Return to Savagery, Chapter II” by Franklin C. Johnson. “Wait a minute,” I thought, “what happened to Chapter I?” I went back to the previous issue only to discover that pp. 43 through 50 are missing–no wonder it seemed so spare in content.

So, we have chapters II, III, IV, and V and, at the end of chapter V, we are informed that the account is “to be continued”.

These essays are of particular interest to me since they deal with the landscape, Indian, and territorial life of South Dakota and Wyoming and I live in Wyoming, which is, however, admittedly a very large state and these reports deal largely with the northern part of the state and I live in the southern part. Nonetheless, there’s some fascinating material about an area that’s relatively close by.

In Chapter II, we find this wonderful observation:

“We emerged from the Black Hills at Spearfish, a beautiful little prairie town, and it was there I saw my first cowboy. I was disappointed. The reckless and romantic character that was the beau ideal of my youthful days was not what I beheld. Those that I saw were very ordinary looking men indeed. Later I learned that the cowboy’s life is one of unremitting toil and that very little poetry creeps into it. Like the Homeric hero or the Theocritean shepherd, the cowboy shows more brilliantly when viewed through the penumbra of romance, than through the spectacles of critical reality.”

What a marvelous insight. It used to be that when young children were asked what they wanted to be when they grew up, three popular choices were fireman, policeman and cowboy. Today I suspect the answers would be billionaire CEO, multimillion dollar rock star, or multimillion dollar professional athlete. Television shows and the events of 9/11 and after robbed being a policeman or fireman of most of its romance and the desperate loneliness of the cowboy as represented in the film Brokeback Mountain demolished the myth of an exciting life in the wilderness. Enormous numbers of humans long for adventure and excitement and escape from the boredom and routine of everyday life; how else can one explain how Napoleon got nearly 600,000 men to join his army and then march into Russia? The thrill of being a soldier is another romantic misadventure and distortion.

In Chapter III, Mr. Johnson tells of how his camping party crossed over into Wyoming and went to the town of Sundance and then further west. They traveled by wagons and horses and progress was slow, often difficult, and monotonous. He describes a rather bleak landscape of buffalo grass, sage-brush, alkali soil, cactus, and prairie dogs. He gives a good description of the prairie dog:

“These cute little dogs, however, amused us greatly. These little animals belong to the genus Cynomys of the family Sciurids. They are not at all related to the dogs, as the popular name implies, but are very closely allied to the tree and ground squirrels , from which they differ only generically; the name was given to the little creatures, simply because the ordinary utterance of the animals is a chattering noise somewhat like the yelp of a dog. They are considerably larger than the squirrels, being about a foot in length, exclusive of the tail, which is short and from two to nearly five inches in length, according to the species.”

These animals can form colonies or “towns” as they are known, consisting of hundreds of individuals. Ranchers do not find them amusing because horses, cattle, sheep, and goats can trip on the burrow holes and seriously injure themselves. Today developers and animal rights advocates often find themselves at odds when the developers want to kill off prairie dog towns in order to use the land.

Johnson also mentions the common prickly-pears.

“The cactus that is so abundant in Wyoming is small and grows close to the earth, and bears beautiful red and yellow flowers. By the natives it is called the prickly-pear plant. The cactuses are very strange plants–as peculiar structurally as they are bizarre and grotesque in outer appearance. In the first place they have no leaves. What look like leaves in certain jointed cactuses are really flattened and extended stems...When a rainfall occurs on the great plains, the roots and rootlets eagerly drink it all up in a great hurry, and store it away at once in the soft and spongy cellular tissue, of which the main part of the plant is wholly formed.”

Cacti are fascinating objects for microscopical investigation from the spines to the soft tissue to the strange rootlets with which they anchor themselves in the sandy soil.

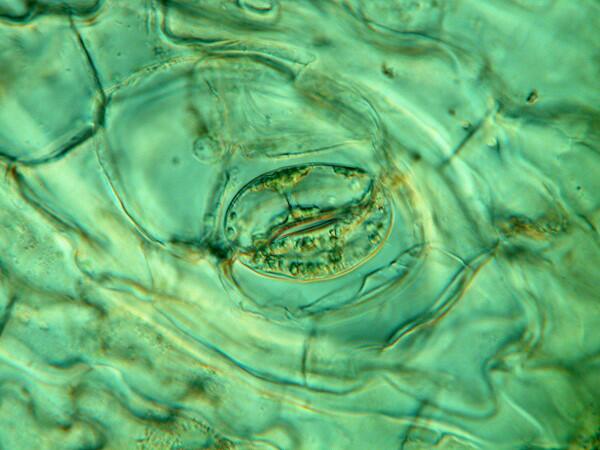

Below is a section of catus showing one of the stomata and some typical surrounding cells.

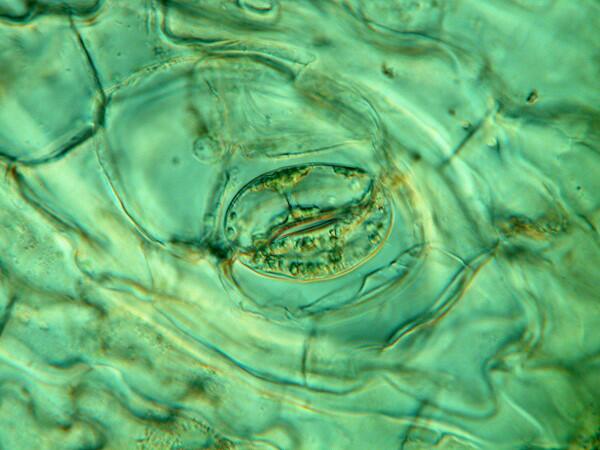

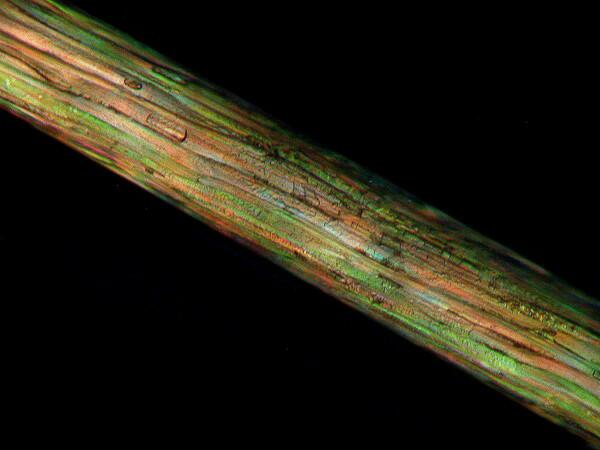

The spines are often birefringent and under polarized light show up in striking colors and you can see in the image below.

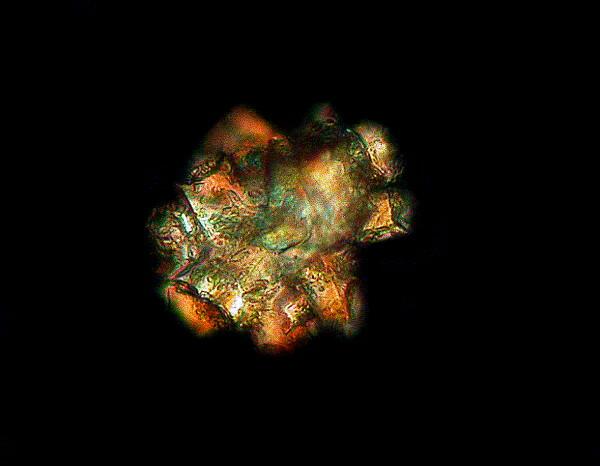

Also, there are frequently crystalline inclusions in cacti and the geometric character of the one below is of special interest.

Every spring and summer when I wander out onto the high plains around here, I find large numbers of these plants and Mr. Johnson is quite right in saying that the flowers are beautiful. On 2 or 3 occasions, I attempted to transplant a specimen or two into one of our flower beds–sadly, without success; they emphatically do not like to be disturbed.

A good portion of the rest of this chapter is devoted to “a rather thrilling experience”. This shows what different interpretations one can have of a given set of events; I, for example, would have found them in no way “thrilling”. The events being referred to are the breaking of the axle of their large wagon, the flight of the heavy horses used to pull this wagon, the dispatching of Harry, one of the team members, in the light cart with the other horses to the “small town of Buffalo nearly a hundred miles away” with the axle to have it repaired. However, the next morning, Harry reappears with some small irons obtained from a ranch about 20 miles away with which he thought the heavy wagon could be temporarily restored. When told of the loss of the large horses, he and George, their guide, took the light wagon and luckily found the large horses quietly grazing about 15 miles away at a site where they had previously camped. They brought the horses back and hitched the large team to the light wagon and Harry once more set out for Buffalo. Around noon, they saw Harry returning yet again, riding one horse and leading the other. He had been driving straight across the prairie, not following what rough trails there were, when the wagon and the team went down into a hole and he could not repair it. So, George, Harry, and Mr. Johnson took the irons, tools, and ropes, and were able to repair and extract the wagon. Harry once more set out for Buffalo and the others returned to camp. It was anticipated that he would be gone several days, but he returned that night. He had learned from a cowboy he happened to encounter that there was a ranch only15 miles away and that it had a blacksmith shop.

“The place was the property of a Mr. Montcrieffe, the younger son of an English baronet, who had adopted ranch life for his health.”

For his health? I find that assertion as odd as Johnson’s claim that the adventures with the wagons were “rather thrilling”. Remember, this is during the 1890s; some Indian tribes are still hostile; there were and are rattlesnakes and black widow spiders in parts of that area; there was no insect repellent or sun-screen lotion; this is high desert and water could be scarce and hard to find and even clear, cold streams could be infected with Giardia from ruminants. Speaking of ruminants, an encounter with a bull moose, elk, or buffalo could prove dangerous as well. The days were hot; the nights were cold; there were no comfortable sleeping bags, and no McDonald’s to stop at for a quarter-pounder and a mug of coffee. Ah, how soft industrialization and technology have made us. The experiences Johnson recounts are not my idea of fun and, to paraphrase the end of Hamlet’s soliloquy, “Thus comfort does make cowards of us all.” However, in my own defense, I will say that I’m not quite as extreme as some of my friends and colleagues who think that any place that isn’t paved is primeval wilderness and they wouldn’t venture there on a bet.

At the end of this chapter, Johnson mentions that his party has missed a roundup, but he describes what he has learned about them and returns to the theme of how cowboys’ lives are falsely romanticized.

“During the round-up there are but two meals a day. Breakfast is long before sunrise, and dinner when the day’s work is over. After dinner is a period of rest and enjoyment. the appetites, sharpened by fifty to sixty miles hard riding, have been appeased. Unlucky candidates for the duties of night herd have gone disgusted and swearing from the camp to their lonesome watch over the restless cattle, and there is nothing to do but talk over the day’s adventures, play cards, smoke and tell stories. The anticipated routing out at four o’clock in the morning cuts short the evening pleasures, however, and by the time dusk changes into the early darkness of the spring the camp is asleep. There is much hard work and little pleasure in the cowboy’s life.”

I am deeply torn by such an account because, while I am by no means a defender of the notion of hardship for the sake of building character, I worry that the emphasis on comfort, convenience, and ease is robbing us of a creative dimension of our humanity. And yet, even though I am a strong defender of much of Nietzsche’s philosophy, I think that his assertion that “that which does not kill me makes me stronger” is an outrageous (and dangerous) piece of adolescent nonsense. I understand what he was trying to articulate, but that particular formulation has become a superficial catch phrase. It is only in the rare instance that suffering ennobles; more usually it crushes the spirit. On the other hand, our technological comforts and distractions can rob us of our freedom in a variety of significant ways and freedom becomes the theme of the opening paragraph of Chapter IV.

“Day by day, as we wandered aimless over the plains, the fascination of savage life wound its sliver snare-threads closer and tighter upon me. No man with a soul can resist the pleasure of feeling absolutely free–free to shout and yell, to dress as one pleases, to be lazy if so inclined; the freedom to eat freely and to drink copiously–the freedom of utter unrestraint. To meet nature face to face, and put your hand familiarly against her cheek, and talk to her as if an equal–that is joy.”

A complex man, our Mr. Johnson. An individual who wants to embrace the “savage life” and to be unrestrained, but someone who, at the same time, maintained high principles. It becomes very clear that his sympathies rested with individuals and not corporations, agencies, or governments as we shall soon see.

He describes the abundance of game; buffalo, elk, black-tail deer and antelope. He also describes how, as his caravan approaches the town of Sheridan, Wyoming, the landscape softens: “where the grass grows, and water runs, and trees mount skyward and spread sweet shade.” He praises Sheridan and sees great promise for its development. At the end of this chapter he mentions the rustlers’ war of Sheridan and we get an interesting insight into his character.

The truth of the controversy, as I saw it, is that the ‘rustlers,’ as they have been indiscriminately called, comprise the bone and sinew of the great plain people of Wyoming. The cause of the late trouble was not, as alleged, the stealing of certain cattle by degenerate settlers. The real cause of the trouble seemed to me to be accounted for by the fact that many of the big cattle companies are in a country where they have no legal right...There was no excuse or justification for the war of the big cattle owners against the small ranchmen.”

Today, in the United States at least, farming and ranching are largely “factory” enterprises; everything is mass produced which makes it cheaper, but also more vulnerable to contamination either through ignorance, greed, neglect, or design. Over the last several decades small ranches and farms have been going bankrupt at an accelerating rate. The trend that Johnson saw seems to be irreversible.

Chapter V (which is that last one I have access to) is exceptionally interesting in two respects: Johnson’s account of woman suffrage and his views on the Indians and both are worthy of quotation.

“While at Sheridan I was careful to inquire how woman suffrage was regarded, and everyone agreed that it was a perfect success. The women of Wyoming seem to be glad of the chance to vote, and I heard of no case where woman suffrage has led to domestic infelicity. The women have suffered no loss of respect and consideration on account of the use of the suffrage, and everyone told me that they are fully as intelligent and independent as men in the exercise of the right.”

Wyoming was the first to allow women to vote in all elections; women were elected to the state assembly; women were appointed to juries, and Wyoming had the first woman governor, Nellie Taylor Ross. Apparently, there were indeed a considerable number of intelligent and independent women in this area at this time. I found it amusing that Johnson assessed that there were no instances of “domestic infelicity” as a consequence of woman suffrage. I doubt if the same could be said today. One gathers from the tenor of his comments that most of his information on this issue was gleaned from conversations with men, which in some ways, makes his comments all the more remarkable in declaring suffrage “a perfect success.”

His opinions regarding the Indians are so progressive as to be astonishing for that period.

“The Crow Indians seemed to us to be a peaceful tribe, and the trouble that does occasionally occur among them is, I think greatly due to the manner in which the government treats them. It is absurd to make paupers of the Indians by giving them neither food nor clothing, and it is much worse than foolish to place any people under autocratic rule in the United States, and especially such a liberty-loving people as the Indians. It is also useless to give money destined for private individuals into the hands of politicians. The Indian cannot be chained to the ground and forced to farm whether he will or not. Until the red man is a citizen, subject to the same privileges and penalties as are other men, no improvement in his condition can be expected.

I have noticed in the papers this winter occasional telegrams to the effect that the Crows have been slaughtering the cattle of stockmen and settlers who have ranches near the reservation and that there are rumors of serious trouble; but I am willing to wager that this status of affairs was brought about by the cattlemen more than by the Indians. The ranchmen look with greedy eyes upon the fertile lands of the reservation and hate the Indians, who keep the white man’s cattle off the rich, green banks of its many streams.”

And here Mr. Johnson’s narrative ends for us. I would be greatly interested in the rest of his account, but I have been unable to track down any further copies of The American Magazine of Natural Science. Clearly Johnson was able to grasp the complexities of the situation and not rush to judgment against the Indians. He himself seems to have been somewhat of a rover and thus admired the nomadic life of the Indians. His observations about the foolishness of trying to put them under autocratic rule still resonate today. Why more than a century later do we still have a Bureau of Indian Affairs? Indeed, why are there still reservations?

Johnson clearly had a fascination with the Indian cultures and in this chapter provides very abbreviated, but very interesting remarks about moccasins and language. He learned that the tribe of an Indian could be determined by the moccasins both on account of the construction, but most especially from the character of the bead work.

His observation about communication is too good not to include.

“One of the things that most interested us was the dialect of hands, arms and features in common vogue between the white men and the Indians. A cowboy meets a dozen savages, all probably of different tribes, and though no two have ten articulate words in common, they converse for hours in dumb show, understanding each other perfectly.”

A very good example of the fact that when there is a strong positive will to communicate, it is possible even without a common spoken language. The summer before last, a marvelously adventurous former graduate student of mine, Luke Glowacki, decided that he had been isolated too long in America and took off for Ulan Bator in Mongolia. He didn’t know a word of any of the relevant languages; he traveled out across the countryside with nomadic tribes and not only survived, but had a terrific time. He managed to communicate quite successfully largely through gesture and facial expressions. He described how there was a loss of self-consciousness and reserve in the use of body language which he compared to the Italians with whom he spent some time in Italy this last summer. He came back full of stories, many of which I have not yet had the opportunity to hear, but he did describe a special intuitive understanding that developed between him and the friends he made, based in part on shared experience and the ability to find simple things funny as when they were shoveling sheep and goat manure in slippery mud. Both he and his friend appropriated their experience in the same way. So, Luke, the next time we manage to get together, I want to know much more about this whole communication process you experienced.

Franklin C. Johnson was clearly an individual, like my friend Luke, who wanted to confront nature directly, to experience the ways of other people first hand, and to use his freedom to form his own opinions rather than relying on rumors and the reports of others. I think I would have enjoyed knowing Mr. Johnson.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .