"The world is a meadow made for insects, not for men. A place for take-offs & landings and stunning aerobatics that in comparison to the most advanced manned flight it is but the first faltering step of a child" (Stephen Dalton).

Order: Odonata

Suborder: Anisoptera

Family: Aeschnidae

Subfamily: Aescninae

Dragonflies are also known as mosquito hawks or darners; they are mainly found in or around meadowed areas and ponds.

Dragonflies are territorial and classified as "hanger's on". "Hanger's on" are one of the oldest forms of insects.

Back in the Carboniferous period, insects metamorphosized in a step-by-step process; wings were acquired at the end of this transformation.

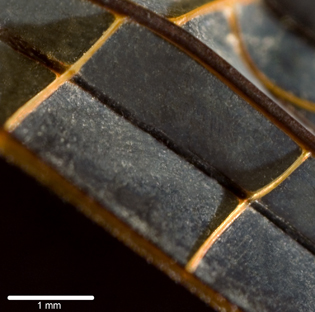

At the juvenile stage, dragonflies are called nymphs. Nymphs start life in water, where it is breathed through the rear rectal chamber of the abdomen. Towards the end of metamorphosis, feeding habits and physical attributes change; marking a transition to adulthood.

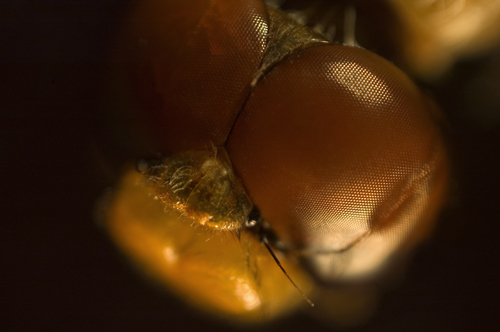

The eyes are enormous; covering much of their movable head; their finger-like mouths move food between the upper and lower flap-shaped lips. The legs of a dragonfly are bristly and are used to transfer food to the mouth.

Diet consists mainly of mayflies, midges, mosquitos, and moths. They are carnivorous and sometimes feed on juvenille nymphs.

Dragonflies form a unique mating-wheel; unlike any in the animal kingdom. Males deposit sperm via the abdominal tip when the female is securely fastened to the male's body by a pair of fitted pinchers located on the neck. When ready, females release fertilized eggs on the surface film of freshwater.

Migration occurs regularly between the summer and winter seasons.

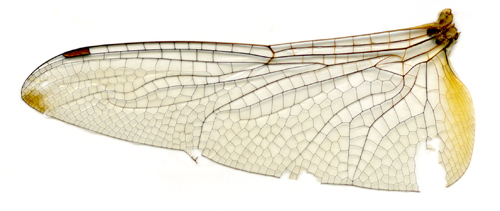

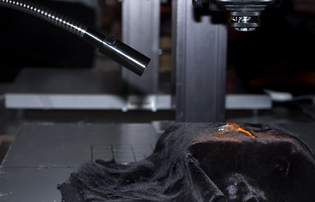

Using a fiber optic light source and a NikonD70 camera with Nikon bellows and a 38 mm thimble lens attached via USB cord to a Macintosh computer with Nikon Capture software as a set-up; I shot the specimens. Due to the upcoming winter season, my methods to capture live dragonflies proved fruitless, but I was able to obtain several specimens of preserved Aeschnidae Odonata from Wars's Natural Science located in Rochester, New York. The Odonata were kept in a 24% ethanol solution called grasshopper juice. To capture the veination in the thin membrane of the wing, I used side-lighting to prevent refraction off the wing surface. Also used during this project was an Epson Perfection 4870 scanner; the pictures on this site with the white backgrounds were produced from this piece of equipment. A labjack was used to raise and lower the specimen into focus; a black cloth was used to absorb reflections. Due to the fragile nature of the specimens, tweezers were used during most handling times. An exacto-knife was used to dissect different parts of the dragonfly and a petri-dish filled with water was utilized to prevent the specimen from drying out.

Difficulties I encountered while photographing the specimens included: keeping the specimen intact, preventing the specimen from drying out, minimizing reflections and diffraction from the glossy-body, and preventing dust & hair from sticking to the sample. I had to clean the dragonflies several times using a magnifying glass and a small set of tweezers.

By side-lighting the dragonfly and by directing light rays parallel to the specimen, optimum light will be achieved. From the above suggestions you, yourself may capture similar images. Final touches were digitally processed through Adobe Photoshop CS2.

All images and text are copyright Jennifer Hill 2007. For permission to use these images or questions or comments regarding this article please email Jennifer Hill, or Professor Michael Peres.

I am currently a third year Biomedical Photographic Communications student at Rochester Institute of Technology . Feel free to email me at jjh6100@rit.edu or at the link above.

Sources:

Dalton, Stephen. Borne on the Wind: The extraordinary world of insects in

flight. N.p.: n.p., 1975.

Needham, James G., and Hortense Butler Heywood. A Handbook of the Dragonflies of

North America. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, 1929.

Return to index of articles

by students on the 'Principles and techniques of photomacrography'

course, November 2007,

Biomedical Photographic Communications (BPC)

program at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT).

Article hosted on Micscape Magazine (Microscopy-UK).

|

||

|---|---|---|