As I state in the

paragraph on methods of

observation and documentation, the simple photographs taken by

most microscopists do

not

allow a precise species determination. Names applied to the specimens

shown

here are

compatible with the key. But the absence of any complementary data

only allows

"probable" identifications. I hope that in the future any

microscopist having a Stentor

under their objectives (including me, of

course, if

I have the chance to find them anew) compiles all the relevant

information which they will need to do a positive identification.

INTRODUCTION

One genus

which readily draws the attention of microscopists who observe

the freshwater protists, is Stentor,

whose first species was named 231

years

ago. Generally of large size, sometimes numerous, and very frequent,

the stentor

is easy to study even with low powers. The desire to give a

denomination (a

specific name) to the studied specimen conflicts with the shortage of

descriptions in the reference books.

My first

intention was to produce a small key of the more common species

of the genus. But, aside from the difficulty in deciding which species

to

exclude, the study of the subject made me more interested in a broader

key, to encompass not

only the Stentor

genus, but also the family which includes it and two

other closely related families. This article is the result of all these

inquiries.

The heavily annotated key

that I add at the end, tries to offer microscopists the best

and

fastest

taxonomic determination of their specimens. One cannot however regard

this method

as infallible. A few characters from one key, even if they are

important, are

not enough to replace a complete description of the species. The big

task

that faces the taxonomist (professional or not) who is interested for

the first time in the stentors

is clearly illustrated by the number of publications on the genus,

which,

according to Foissner and

Wölfl 1994 exceeds 1300.

Individuals

of each species can present great

variations, which can require for their definition a somewhat

deeper

study, with advanced techniques, like silver impregnation for

example. The

specialists have not even been able to completely agree on the

characters that are

used to define and to differentiate the Stentor

species.

There exists however

a

series of characters which can be observed

without ambiguity with average powers and which make it possible to

attempt

the primary identification of even live specimens. These characters

are, in order of ease

of

observation:

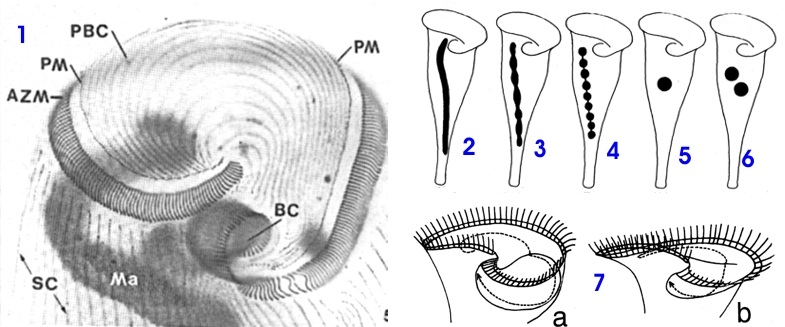

2 - the shape and size of the nucleus,

3 - the form of the apical sector or peristomial bottom, and the presence or not of one "buccal pouch",

4 - the presence or not of pigmented granules between the longitudinal lines of cilia

5 - obviously the color of the pigment if it is present

6 - the existence or not of a total or partial gelatinous tube (lorica) in which the individual lives

|

| Fig. 2 - description of the anterior end of one Stentor roeselii (silver impregnation): AZM, Adoral Zone of Membranelles. BC, oral cavity. Ma, Macronucleus. PBC, Ciliary lines of the "peristomial bottom", PM, parorale membrane. SC, ciliary somatic lines. Figs. 2-6, different nuclear forms: 2 vermiform, 3 nodular, 4 moniliform (in chain), 5 only one ball, 6 more than one ball. Fig. 7a- peristomial bottom with a "buccal pouch", 7b shows a peristomial bottom without "buccal pouch". (One of the lines of cilia of the peristomial bottom is drawn for showing better the position and form of the pouch. Figs 1-6 modified from Foissner and Wölfl 1994, Fig. 7 modified from Kumazawa 2002. |

|

|

|

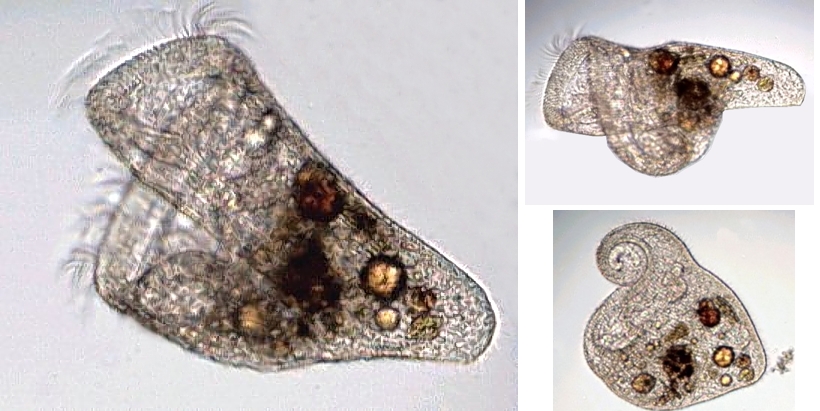

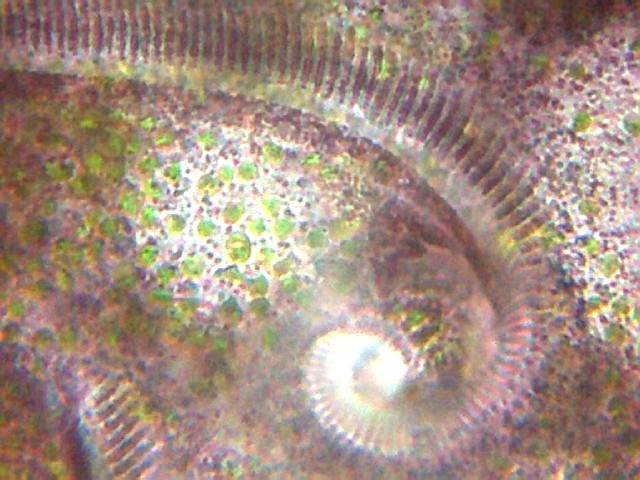

| Fig.

3 Stentor amethystinum - AZM

sinking to the mouth. In this and the following pictures we can see the

ectoplasm with its pigment granules and the zoochlorelles. |

Fig. 4 Stentor amethystinum - disposition of the ciliary lines (clear lines) and the bands of pigmented granules. The background is strewn with zoochlorelles. | Fig. 5 Another species, showing the cytoplasm deprived of zoochlorelles, but with food vacuoles full with chlorelles. See the moniliform nucleus. |

| above three images are from Christian Colin | ||

|

|

| Fig. 6 - prob. St. Muelleri from Cancún.

We can see the lines of ciliary insertion. Fixed with hot AFA, stained

with Fast Green, mounted in NPM. In the right insert the moniliform nucleus

of

ellipsoidal beds is shown. |

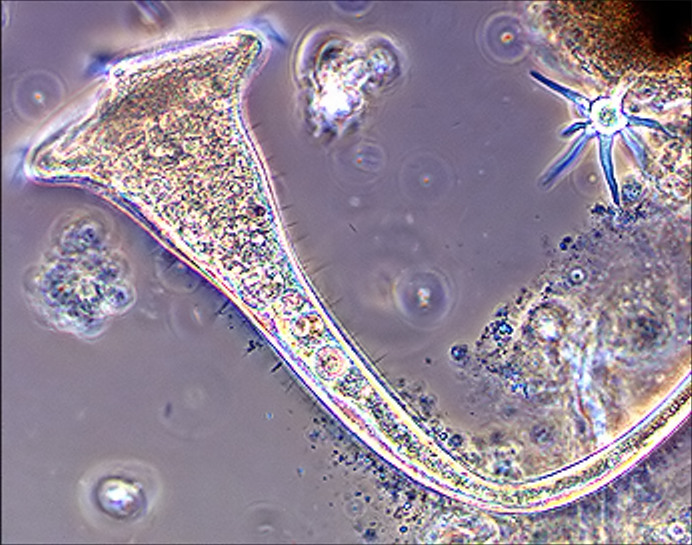

Fig

7 - Stentor

picture in phase contrast. Although the inner details are not

very visible, cilia differentiate in short somatic cilia and stereocilia

or rigid cilia, more dispersed than the somatic ones. |

|

Fig. 7 reproduced by the kindness of Rick Gillis, PH.D, from his site HTTP://bioweb.uwlax.edu/zoolab/Table_of Contents/Lab-2b/Stentor/Live_ Stentor_1/live_stentor_1.htm |

|

Some confirmatory characters, better observed with a larger power (400x), are the width, the number and the position of the longitudinal bands of ectoplasmic granules, the presence, the number and distribution of rigid cilia (stereocilia) between the normal ones, the size, and forms of the extended individuals.

|

Conditions for the identification Careful

live

study is essential. The best data at weak enlargement (40x and 100x -

objectives 4x and 10x, with an eyepiece 10x) will be obtained on

individuals

fixed on a substrate and extended in their normal attitude of food

gathering. The

specimens can be anaesthetized by mixing carefully in the liquid which

contains

them small drops of a 1% solution of

sodium or potassium iodide, but it is very difficult to obtain a

perfect

anaesthesia in conditions of total extension. The use of

strong

enlargements (400 - 1000 X) can be used only on specimens carefully

compressed

between coverslip and slide. One can resort for this "to the petroleum

jelly compressors". Lubricate the palm of the hand with a very thin

layer

of solid petroleum jelly (Vaseline) and pass on both opposite borders

of a coverslip.

With a micropipette select one or several individuals and drop them in

the centre of a slide. Apply the coverslip over the very small drop of

water containing the protozoa, in

such a way that the drop remains in the centre of the cover. By using

one or two mounted needles, the small quantity of petroleum

jelly will make it possible

to apply and vary the pressure on the specimens, while the

two open

borders will allow water addition, anaesthetics or other reagents with

a

micropipette. If one wishes to make longer observations, use a seal with paraffin, or a microaquarium. Using phase contrast illumination can be useful to

define ciliature and even better to identify rigid cilia, but it does

not appear

suitable for the study of internal organization, because there exists

in the

cytoplasm too many inclusions of very similar index of refraction. It

is

advisable to try the darkfield stops and contrast filters. The

protozoan

must be

observed in all possible positions, as it is free, or as adhered to the

substrate, if it is sessile. Many of these details and especially the color of the ectoplasmic bands of granules, can only be interpreted by microscopists, during the direct examination of the live individual. To highlight in pictures the required identification details, they must be taken at several powers and with a high resolution digital camera (if possible with a 2 or more Mpx), specially focusing on the important details (e.g. ex. stereocilia). |

Consulted Bibliography

- As well as Kahl’s

1935 basic and

irreplaceable work, we

consulted that of Corliss

1961 and Foissner and Wölfl 1994,

which carries out a brief

but complete and informative revision of the genus, by treating all the

species, almost 50,

described after the traditional work of Ehrenberg 1838. They

recognize as valid only 18

of those species.

The Lynn 2002 publication on line, which summarizes the genera and the type species of ciliates is also very useful to see in detail the position of Stentor in the traditional taxonomic system of Ciliatea.

I thank very much Professor Daniel

Nardin, whose kindness

and effort allowed me to

consult the article of Fauré-Fremiet

1936, on Condylostoma

auriculata which

will be much commented on subsequently.

Systematic position of the Family

Below are links providing an introduction

to the taxonomic categories and

traditional hierarchies. If the reader does not have any background on

taxonomy I

suggest they must be your

first reading (at least the

first two).

http://www.niles-hs.k12.il.us/rutgle/Classification.ppt

http://anthro.palomar.edu/animal/default.htm

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/clad/clad4.html

Parts of a specific name

Stentor multiformis (O F

Müller, 1786) Ehrenberg

1838

1

2

3

4

1 - name of the genus (it is always written with a capital letter)

2 - name of the species (one always writes it with small letters)

3 - name of the researcher who described the species for the first time, but probably in a different genus, and dates of the description.

4 - name of the researcher who assigned the species to the correct genus, and year of the revision work

When there have not been modifications of the name since its description one only uses 4, ex:

FAMILY STENTORIDAE

Taxonomic situation

and its

relations according to Lynn

2002 (see the references).

Phylum Ciliophora Doflein, 1901

Class Heterotrichea

Stein, 1859

Order Heterotrichida

Stein, 1859

Family Stentoridae Carus, 1863

However in 1936 Fauré-Fremiet, had already proposed this species, which he described and illustrated in detail from specimens collected at Concarneau (Bretagne, France), is regarded as a member of the genus Condylostoma, corresponding to the family Condylostomatidae, and its criterion has enjoyed more acceptance from the protozoologists, who rejected Condylostentor, created without bringing a valid criticism to the work of Fauré-Fremiet. Consequently Stentoridae continued to be a family with only two genera (one of them very poorly known) until 2002 when almost at the same time two new genera Maristentor and Heterostentor, were described and appear to be accepted for the moment.

|

are consequently

the families closely related

to the Stentoridae. I

want to

propose a key for the reader to recognize the three families. Read

carefully,

because

I include extended comments and some images between the various

options. The key is based on

dichotomous

selections. There are only two options, one is true, the other not. You compare

your specimens with the options and decide which is in conformity with your

material. The option gives you a denomination, or sends you to another

dichotomous option.

B (A)

Body large, (700-900 microns)

contractile; with one undulating

membrane very visible on the right* anterior end;

one Adoral

Zone of Membranelles (AZM)

delimits a peristomial bottom without cilia

................................................................................................... CONDYLOSTOMATIDAE

With one vast

peristome, V shaped; macronucleus moniliform

…………………………..................................................... Condylostoma Bory

de Some species of Condylostoma can be

seen at

Note: Kahl presents

and illustrates moreover S. auricula S. auricula

according to Fauré-Fremiet 1936, and

Foissner and Wölfl 1994 is most probably a species of Condylostoma,

however Kahl allots a single

and oval

nucleus to it. Obviously this species (if it exists) needs to be

newly found and well described. It was found only in 1881 among bryozoa

in

the aquarium at Westminter.

Included here is Fabrea Henneguy 1910, a genus found in brackish water

(up to 20% of salinity), often found in saltworks, and Climacostomum,

Stein 1859,

from fresh and

brackish waters. Species

of the two genera are relatively small (around 300 microns). Image of Fabrea salina HTTP

://power.ib.pi.CNR.it/groups/fabrea/ottico.HTML

|

Now we can go to the Stentor species key